Causes of Forgetting

Forgetting can often be obnoxious or even embarrassing. But as we explore this module, you’ll learn that forgetting is important and necessary for everyday functionality. [Image: jazbeck, https://goo.gl/nkRrJy, CC BY 2.0, https://goo.gl/BRvSA7]

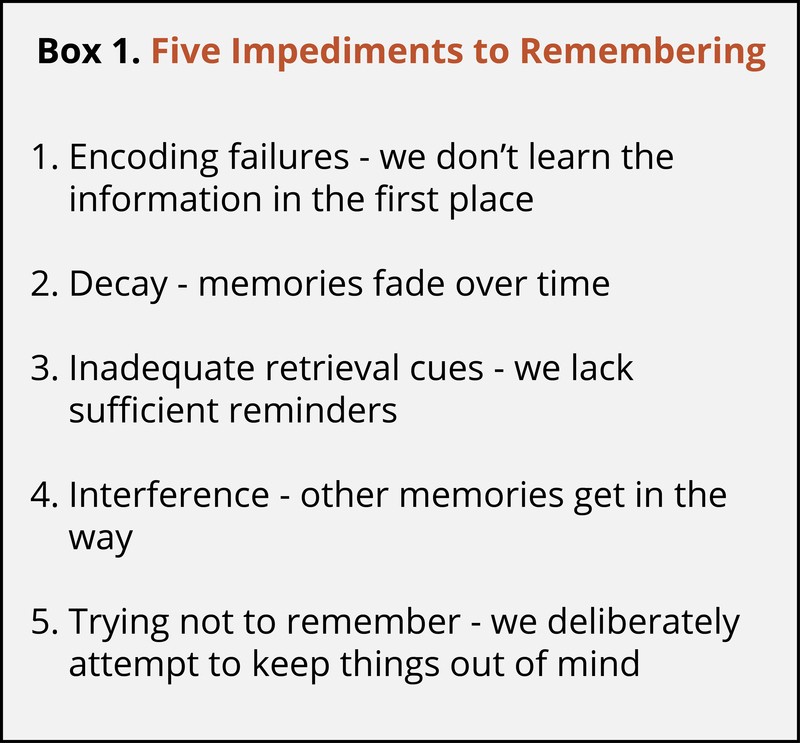

One very common and obvious reason why you cannot remember a piece of information is because you did not learn it in the first place. If you fail to encode information into memory, you are not going to remember it later on. Usually, encoding failures occur because we are distracted or are not paying attention to specific details. For example, people have a lot of trouble recognizing an actual penny out of a set of drawings of very similar pennies, or lures, even though most of us have had a lifetime of experience handling pennies (Nickerson & Adams, 1979). However, few of us have studied the features of a penny in great detail, and since we have not attended to those details, we fail to recognize them later. Similarly, it has been well documented that distraction during learning impairs later memory (e.g., Craik, Govoni, Naveh-Benjamin, & Anderson, 1996). Most of the time this is not problematic, but in certain situations, such as when you are studying for an exam, failures to encode due to distraction can have serious repercussions.

Another proposed reason why we forget is that memories fade, or decay, over time. It has been known since the pioneering work of Hermann Ebbinghaus (1885/1913) that as time passes, memories get harder to recall. Ebbinghaus created more than 2,000 nonsense syllables, such as dax, bap, and rif, and studied his own memory for them, learning as many as 420 lists of 16 nonsense syllables for one experiment. He found that his memories diminished as time passed, with the most forgetting happening early on after learning. His observations and subsequent research suggested that if we do not rehearse a memory and the neural representation of that memory is not reactivated over a long period of time, the memory representation may disappear entirely or fade to the point where it can no longer be accessed. As you might imagine, it is hard to definitively prove that a memory has decayed as opposed to it being inaccessible for another reason. Critics argued that forgetting must be due to processes other than simply the passage of time, since disuse of a memory does not always guarantee forgetting (McGeoch, 1932). More recently, some memory theorists have proposed that recent memory traces may be degraded or disrupted by new experiences (Wixted, 2004). Memory traces need to be consolidated, or transferred from the hippocampus to more durable representations in the cortex, in order for them to last (McGaugh, 2000). When the consolidation process is interrupted by the encoding of other experiences, the memory trace for the original experience does not get fully developed and thus is forgotten.

At times, we will completely blank on something we’re certain we’ve learned – people we went to school with years ago for example. However, once we get the right retrieval cue (a name perhaps), the memory (faces or experiences) rushes back to us like it was there all along. [Image: sbhsclass84, https://goo.gl/sHZyQI, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://goo.gl/rxiUsF]

Both encoding failures and decay account for more permanent forms of forgetting, in which the memory trace does not exist, but forgetting may also occur when a memory exists yet we temporarily cannot access it. This type of forgetting may occur when we lack the appropriate retrieval cues for bringing the memory to mind. You have probably had the frustrating experience of forgetting your password for an online site. Usually, the password has not been permanently forgotten; instead, you just need the right reminder to remember what it is. For example, if your password was “pizza0525,” and you received the password hints “favorite food” and “Mom’s birthday,” you would easily be able to retrieve it. Retrieval hints can bring back to mind seemingly forgotten memories (Tulving & Pearlstone, 1966). One real-life illustration of the importance of retrieval cues comes from a study showing that whereas people have difficulty recalling the names of high school classmates years after graduation, they are easily able to recognize the names and match them to the appropriate faces (Bahrick, Bahrick, & Wittinger, 1975). The names are powerful enough retrieval cues that they bring back the memories of the faces that went with them. The fact that the presence of the right retrieval cues is critical for remembering adds to the difficulty in proving that a memory is permanently forgotten as opposed to temporarily unavailable.

Retrieval failures can also occur because other memories are blocking or getting in the way of recalling the desired memory. This blocking is referred to as interference. For example, you may fail to remember the name of a town you visited with your family on summer vacation because the names of other towns you visited on that trip or on other trips come to mind instead. Those memories then prevent the desired memory from being retrieved. Interference is also relevant to the example of forgetting a password: passwords that we have used for other websites may come to mind and interfere with our ability to retrieve the desired password. Interference can be either proactive, in which old memories block the learning of new related memories, or retroactive, in which new memories block the retrieval of old related memories. For both types of interference, competition between memories seems to be key (Mensink & Raaijmakers, 1988). Your memory for a town you visited on vacation is unlikely to interfere with your ability to remember an Internet password, but it is likely to interfere with your ability to remember a different town’s name. Competition between memories can also lead to forgetting in a different way. Recalling a desired memory in the face of competition may result in the inhibition of related, competing memories (Levy & Anderson, 2002). You may have difficulty recalling the name of Kennebunkport, Maine, because other Maine towns, such as Bar Harbor, Winterport, and Camden, come to mind instead. However, if you are able to recall Kennebunkport despite strong competition from the other towns, this may actually change the competitive landscape, weakening memory for those other towns’ names, leading to forgetting of them instead.

Finally, some memories may be forgotten because we deliberately attempt to keep them out of mind. Over time, by actively trying not to remember an event, we can sometimes successfully keep the undesirable memory from being retrieved either by inhibiting the undesirable memory or generating diversionary thoughts (Anderson & Green, 2001). Imagine that you slipped and fell in your high school cafeteria during lunch time, and everyone at the surrounding tables laughed at you. You would likely wish to avoid thinking about that event and might try to prevent it from coming to mind. One way that you could accomplish this is by thinking of other, more positive, events that are associated with the cafeteria. Eventually, this memory may be suppressed to the point that it would only be retrieved with great difficulty (Hertel & Calcaterra, 2005).