Psychological Consequences of Language Use

What are the psychological consequences of language use? When people use language to describe an experience, their thoughts and feelings are profoundly shaped by the linguistic representation that they have produced rather than the original experience per se (Holtgraves & Kashima, 2008). For example, Halberstadt (2003) showed a picture of a person displaying an ambiguous emotion and examined how people evaluated the displayed emotion. When people verbally explained why the target person was expressing a particular emotion, they tended to remember the person as feeling that emotion more intensely than when they simply labeled the emotion.

Thus, constructing a linguistic representation of another person’s emotion apparently biased the speaker’s memory of that person’s emotion. Furthermore, linguistically labeling one’s own emotional experience appears to alter the speaker’s neural processes. When people linguistically labeled negative images, the amygdala—a brain structure that is critically involved in the processing of negative emotions such as fear—was activated less than when they were not given a chance to label them (Lieberman et al., 2007). Potentially because of these effects of verbalizing emotional experiences, linguistic reconstructions of negative life events can have some therapeutic effects on those who suffer from the traumatic experiences (Pennebaker & Seagal, 1999).

By verbalizing our own emotional experiences – such as in a conversation with a close friend – we can improve our psychological well-being. [Image: Drew Herron, https://goo.gl/lKMAv1, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, https://goo.gl/Toc0ZF]

Lyubomirsky, Sousa, and Dickerhoof (2006) found that writing and talking about negative past life events improved people’s psychological well-being, but just thinking about them worsened it. There are many other examples of effects of language use on memory and decision making (Holtgraves & Kashima, 2008).

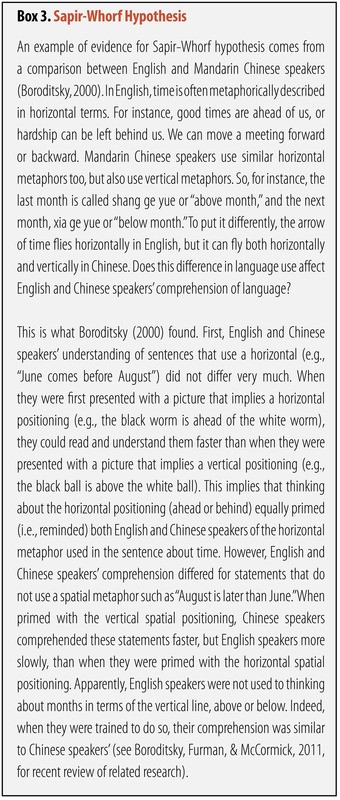

Furthermore, if a certain type of language use (linguistic practice) (Holtgraves & Kashima, 2008) is repeated by a large number of people in a community, it can potentially have a significant effect on their thoughts and action. This notion is often called Sapir-Whorf hypothesis (Sapir, 1921; Whorf, 1956; Box 3). For instance, if you are given a description of a man, Steven, as having greater than average experience of the world (e.g., well- traveled, varied job experience), a strong family orientation, and well- developed social skills, how do you describe Steven? Do you think you can remember Steven’s personality five days later? It will probably be difficult. But if you know Chinese and are reading about Steven in Chinese, as Hoffman, Lau, and Johnson (1986) showed, the chances are that you can remember him well. This is because English does not have a word to describe this kind of personality, whereas Chinese does (shì gù). This way, the language you use can influence your cognition. In its strong form, it has been argued that language determines thought, but this is probably wrong. Language does not completely determine our thoughts—our thoughts are far too flexible for that—but habitual uses of language can influence our habit of thought and action.

For instance, some linguistic practice seems to be associated even with cultural values and social institution. Pronoun drop is the case in point. Pronouns such as “I” and “you” are used to represent the speaker and listener of a speech in English. In an English sentence, these pronouns cannot be dropped if they are used as the subject of a sentence. So, for instance, “I went to the movie last night” is fine, but “Went to the movie last night” is not in standard English. However, in other languages such as Japanese, pronouns can be, and in fact often are, dropped from sentences. It turned out that people living in those countries where pronoun drop languages are spoken tend to have more collectivistic values (e.g., employees having greater loyalty toward their employers) than those who use non–pronoun drop languages such as English (Kashima & Kashima, 1998). It was argued that the explicit reference to “you” and “I” may remind speakers the distinction between the self and other, and the differentiation between individuals. Such a linguistic practice may act as a constant reminder of the cultural value, which, in turn, may encourage people to perform the linguistic practice.