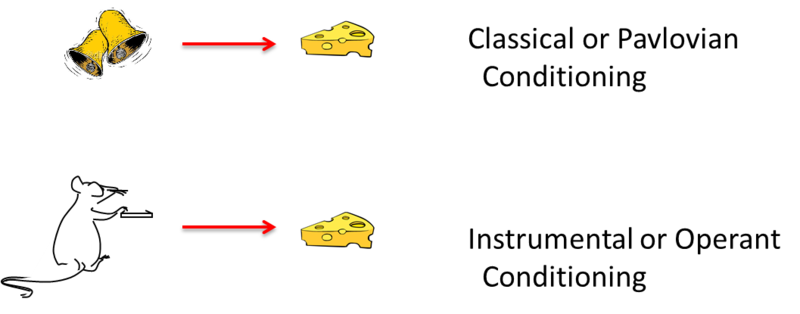

Two Types of Conditioning

Although Ivan Pavlov won a Nobel Prize for studying digestion, he is much more famous for something else: working with a dog, a bell, and a bowl of saliva. Many people are familiar with the classic study of “Pavlov’s dog,” but rarely do they understand the significance of its discovery. In fact, Pavlov’s work helps explain why some people get anxious just looking at a crowded bus, why the sound of a morning alarm is so hated, and even why we swear off certain foods we’ve only tried once. Classical (or Pavlovian) conditioning is one of the fundamental ways we learn about the world around us. But it is far more than just a theory of learning; it is also arguably a theory of identity. For, once you understand classical conditioning, you’ll recognize that your favorite music, clothes, even political candidate, might all be a result of the same process that makes a dog drool at the sound of bell.

The Pavlov in All of Us: Does your dog learn to beg for food because you reinforce her by feeding her from the table? [Image: David Mease, https://goo.gl/R9cQV7, CC BY-NC 2.0, https://goo.gl/FIlc2e]

Around the turn of the 20th century, scientists who were interested in understanding the behavior of animals and humans began to appreciate the importance of two very basic forms of learning. One, which was first studied by the Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov, is known as classical, or Pavlovian conditioning. In his famous experiment, Pavlov rang a bell and then gave a dog some food. After repeating this pairing multiple times, the dog eventually treated the bell as a signal for food, and began salivating in anticipation of the treat. This kind of result has been reproduced in the lab using a wide range of signals (e.g., tones, light, tastes, settings) paired with many different events besides food (e.g., drugs, shocks, illness; see below).

We now believe that this same learning process is engaged, for example, when humans associate a drug they’ve taken with the environment in which they’ve taken it; when they associate a stimulus (e.g., a symbol for vacation, like a big beach towel) with an emotional event (like a burst of happiness); and when they associate the flavor of a food with getting food poisoning. Although classical conditioning may seem “old” or “too simple” a theory, it is still widely studied today for at least two reasons: First, it is a straightforward test of associative learning that can be used to study other, more complex behaviors. Second, because classical conditioning is always occurring in our lives, its effects on behavior have important implications for understanding normal and disordered behavior in humans.

In a general way, classical conditioning occurs whenever neutral stimuli are associated with psychologically significant events. With food poisoning, for example, although having fish for dinner may not normally be something to be concerned about (i.e., a “neutral stimuli”), if it causes you to get sick, you will now likely associate that neutral stimuli (the fish) with the psychologically significant event of getting sick. These paired events are often described using terms that can be applied to any situation.

The dog food in Pavlov’s experiment is called the unconditioned stimulus (US) because it elicits an unconditioned response (UR). That is, without any kind of “training” or “teaching,” the stimulus produces a natural or instinctual reaction. In Pavlov’s case, the food (US) automatically makes the dog drool (UR). Other examples of unconditioned stimuli include loud noises (US) that startle us (UR), or a hot shower (US) that produces pleasure (UR).

On the other hand, a conditioned stimulus produces a conditioned response. A conditioned stimulus (CS) is a signal that has no importance to the organism until it is paired with something that does have importance. For example, in Pavlov’s experiment, the bell is the conditioned stimulus. Before the dog has learned to associate the bell (CS) with the presence of food (US), hearing the bell means nothing to the dog. However, after multiple pairings of the bell with the presentation of food, the dog starts to drool at the sound of the bell. This drooling in response to the bell is the conditioned response (CR). Although it can be confusing, the conditioned response is almost always the same as the unconditioned response. However, it is called the conditioned response because it is conditional on (or, depends on) being paired with the conditioned stimulus (e.g., the bell). To help make this clearer, consider becoming really hungry when you see the logo for a fast food restaurant. There’s a good chance you’ll start salivating. Although it is the actual eating of the food (US) that normally produces the salivation (UR), simply seeing the restaurant’s logo (CS) can trigger the same reaction (CR).

Another example you are probably very familiar with involves your alarm clock. If you’re like most people, waking up early usually makes you unhappy. In this case, waking up early (US) produces a natural sensation of grumpiness (UR). Rather than waking up early on your own, though, you likely have an alarm clock that plays a tone to wake you. Before setting your alarm to that particular tone, let’s imagine you had neutral feelings about it (i.e., the tone had no prior meaning for you). However, now that you use it to wake up every morning, you psychologically “pair” that tone (CS) with your feelings of grumpiness in the morning (UR).

After enough pairings, this tone (CS) will automatically produce your natural response of grumpiness (CR). Thus, this linkage between the unconditioned stimulus (US; waking up early) and the conditioned stimulus (CS; the tone) is so strong that the unconditioned response (UR; being grumpy) will become a conditioned response (CR; e.g., hearing the tone at any point in the day—whether waking up or walking down the street—will make you grumpy). Modern studies of classical conditioning use a very wide range of CSs and USs and measure a wide range of conditioned responses.

Although classical conditioning is a powerful explanation for how we learn many different things, there is a second form of conditioning that also helps explain how we learn. First studied by Edward Thorndike, and later extended by B. F. Skinner, this second type of conditioning is known as instrumental or operant conditioning. Operant conditioning occurs when a behavior (as opposed to a stimulus) is associated with the occurrence of a significant event. In the best-known example, a rat in a laboratory learns to press a lever in a cage (called a “Skinner box”) to receive food. Because the rat has no “natural” association between pressing a lever and getting food, the rat has to learn this connection. At first, the rat may simply explore its cage, climbing on top of things, burrowing under things, in search of food. Eventually while poking around its cage, the rat accidentally presses the lever, and a food pellet drops in. This voluntary behavior is called an operant behavior, because it “operates” on the environment (i.e., it is an action that the animal itself makes).

Receiving a reward can condition you toward certain behaviors. For example, when you were a child, your mother may have offered you this deal: “Don’t make a fuss when we’re in the supermarket and you’ll get a treat on the way out.” [Image: Oliver Hammond, https://goo.gl/xFKiZL, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, https://goo.gl/Toc0ZF]

Now, once the rat recognizes that it receives a piece of food every time it presses the lever, the behavior of lever-pressing becomes reinforced. That is, the food pellets serve as reinforcers because they strengthen the rat’s desire to engage with the environment in this particular manner. In a parallel example, imagine that you’re playing a street-racing video game. As you drive through one city course multiple times, you try a number of different streets to get to the finish line. On one of these trials, you discover a shortcut that dramatically improves your overall time. You have learned this new path through operant conditioning.

That is, by engaging with your environment (operant responses), you performed a sequence of behaviors that that was positively reinforced (i.e., you found the shortest distance to the finish line). And now that you’ve learned how to drive this course, you will perform that same sequence of driving behaviors (just as the rat presses on the lever) to receive your reward of a faster finish.

Operant conditioning research studies how the effects of a behavior influence the probability that it will occur again. For example, the effects of the rat’s lever-pressing behavior (i.e., receiving a food pellet) influences the probability that it will keep pressing the lever. For, according to Thorndike’s law of effect, when a behavior has a positive (satisfying) effect or consequence, it is likely to be repeated in the future. However, when a behavior has a negative (painful/annoying) consequence, it is less likely to be repeated in the future. Effects that increase behaviors are referred to as reinforcers, and effects that decrease them are referred to as punishers.

An everyday example that helps to illustrate operant conditioning is striving for a good grade in class—which could be considered a reward for students (i.e., it produces a positive emotional response). In order to get that reward (similar to the rat learning to press the lever), the student needs to modify his/her behavior. For example, the student may learn that speaking up in class gets him/her participation points (a reinforcer), so the student speaks up repeatedly. However, the student also learns that s/he shouldn’t speak up about just anything; talking about topics unrelated to school actually costs points. Therefore, through the student’s freely chosen behaviors, s/he learns which behaviors are reinforced and which are punished.

An important distinction of operant conditioning is that it provides a method for studying how consequences influence “voluntary” behavior. The rat’s decision to press the lever is voluntary, in the sense that the rat is free to make and repeat that response whenever it wants.

[Image courtesy of Bernard W. Balleine]

Classical conditioning, on the other hand, is just the opposite—depending instead on “involuntary” behavior (e.g., the dog doesn’t choose to drool; it just does). So, whereas the rat must actively participate and perform some kind of behavior to attain its reward, the dog in Pavlov’s experiment is a passive participant. One of the lessons of operant conditioning research, then, is that voluntary behavior is strongly influenced by its consequences.

The illustration on the left summarizes the basic elements of classical and instrumental conditioning. The two types of learning differ in many ways. However, modern thinkers often emphasize the fact that they differ—as illustrated here—in what is learned. In classical conditioning, the animal behaves as if it has learned to associate a stimulus with a significant event. In operant conditioning, the animal behaves as if it has learned to associate a behavior with a significant event. Another difference is that the response in the classical situation (e. g., salivation) is elicited by a stimulus that comes before it, whereas the response in the operant case is not elicited by any particular stimulus. Instead, operant responses are said to be emitted. The word “emitted” further conveys the idea that operant behaviors are essentially voluntary in nature.

Understanding classical and operant conditioning provides psychologists with many tools for understanding learning and behavior in the world outside the lab. This is in part because the two types of learning occur continuously throughout our lives. It has been said that “much like the laws of gravity, the laws of learning are always in effect” (Spreat & Spreat, 1982).