Basic Principles

5 The Hierarchy of Evidence

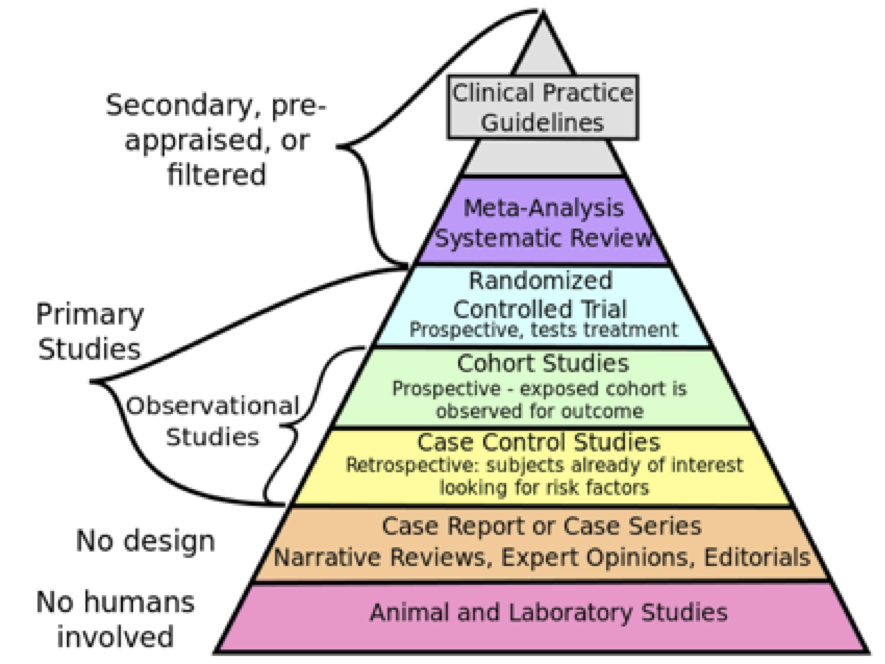

The hierarchy of evidence provides a useful framework for understanding different kinds of quantitative research designs. As shown in Figure 2.1, studies at the base of the pyramid involving laboratory and animal research are at the lowest level of evidence because they tend to be focused on understanding how things work at the cellular level and it is difficult to establish a direct link between the research findings and implications for practice.

This type of research is still valuable because it provides the researcher with a very high level of control which allows them to study things that they can’t do in humans. For example, you could breed genetically modified mice and compare them to regular mice in order to examine the influence of specific genes on behavior. Obviously this type of experiment would be unethical to do with humans but it can provide initial evidence to help us better understand phenomena (in this case, the influence of genes on behavior), intervention, or drug.

The next level includes research with no design and include case reports or case series reports that are commonly used in novel or rare situations (for example, a patient with a rare disease). Expert opinions, narratives, and editorials also fall into this category because they rely on an individual’s expertise, knowledge, and experience which is not necessarily objective.

Above this are retrospective observational studies such as case-control studies or chart reviews that seek to find patterns in data that has already been collected. One downside of this type of research is that the researcher has no control over the variables that were collected or the information that is available.

Next in the hierarchy are prospective observational studies which include cohort studies as well as non-experimental research designs such as surveys. Here the researcher does have control over what variables are measured as well as how and when they are measured. If done well, this approach can strengthen the findings because it provides the researcher with the opportunity to control for confounding variables and bias, take measures to improve response rates, and select their sample.

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are often hailed as “the gold standard” for quantitative research studies in health care because they allow the researcher to control the experiment and isolate the effect of an intervention by comparing it to a control group. However, the inclusion and exclusion criteria for participation can be quite strict and the high level of control is not consistent with real-world conditions, which can reduce the generalizability of findings to the population of interest. Pragmatic RCTs (PRCTs) have begun to gain more popularity for this reason. The goal of a PRCT is to keep the treatment that the control group receives consistent with usual care and the treatment that the intervention group receives consistent with what is practical in the context of real life. While PRCTs don’t provide the same degree of control and standardization as an RCT, the idea is that they provide more realistic evidence about how effective an intervention will be in real life.

Meta-analysis and systematic reviews come next on the hierarchy. The main benefit of systematic reviews and meta-analyses is that they include findings from a number of different studies, and thus, provide more robust evidence about the phenomenon of interest. Whenever possible, this type of evidence should be used to inform decisions about health policy and practice (rather than that from a single study).

It is important to note here that meta-analysis generally occurs as part of a systematic review and combining the data from several studies is not always appropriate. If the designs, methods, and/or measures used in different studies vary considerably then the researcher should not combine the data and analyze it as a group. It is also important not to include multiple studies that use the same dataset because the same sample gets used more than once which will skew the results.

Lastly, at the top of the hierarchy of evidence are clinical practice guidelines. These are at the very top because they are created by a team or panel of experts using a very rigorous process and include a variety of evidence ranging from quantitative and qualitative research studies, white papers and grey literature. Clinical practice guidelines also examine the quality of the evidence and interpret it in order to provide clear recommendations for practice (and often, research and policy as well).

Figure of The hierarchy of evidence (image available to use as per Creative Commons license – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Research_design_and_evidence.svg)