Main Body

5 5/ Value Propositions

Adapted from Principles of Marketing is adapted from a work produced and distributed under a Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-SA) in 2010 by a publisher who has requested that they and the original author not receive attribution. This adapted edition is produced by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing through the eLearning Support Initiative.

SOURCE: Gabby K.

Learning Objectives

-

Explain what a value proposition is.

-

Understand why a company may develop unique value propositions for different target markets.

Value Propositions

Individual buyers and organizational buyers both evaluate products and services to see if they provide desired benefits. For example, when you are exploring your vacation options, know the benefits of each destination and the value you get by going to each place. Before you (or a firm) can develop a strategy or create a strategic plan, you first must develop a value proposition. A value proposition is a 30-second “elevator speech” stating the specific benefits a product or service offering provides a buyer. It shows why the product or service is superior to competing offers. The value proposition answers the questions, “Why should I buy from you or why should I hire you?” The value proposition becomes critical in shaping strategy.

The following is an example of a value proposition developed by a sales consulting firm: “Our clients grow their business, large or small, typically by a minimum of 30% to 50% over the previous year. They accomplish this without working 80-hour weeks and sacrificing their personal lives” (Lake, 2009).

Note that although a value proposition will hopefully lead to profits for a firm, when the firm presents its value proposition to its customers, it does not mention its own profits. The goal is to focus on the external market or what customers want. For instance, Beaches, an all-inclusive chain of resorts for families, must explain what its value proposition is to customers. Why does a Beaches resort provide more value to vacationing families?

SOURCE: Thorsten Technoman.

Firms typically segment markets and then identify different target markets, or groups of customers, they want to reach when they are developing their value propositions. Be aware that companies sometimes develop unique value propositions for different target markets just as individuals may develop a unique value proposition for different employers. The value proposition tells each group of customers (or potential employers) why they should buy a product or service, vacation to a particular destination, donate to an organization, hire you, and so forth.

Once the benefits of a product or service are clear, the firm must develop strategies that support the value proposition. The value proposition serves as a guide for this process. With our sales consulting firm, the strategies it develops must help clients improve their sales by 30% to 50%. Likewise, if a company’s value proposition states that the firm is the largest retailer in the region with the most stores and best product selection, opening stores or increasing the firm’s inventory might be a key part of the company’s strategy. Looking at Amazon’s value proposition, “Low price, wide selection with added convenience anytime, anywhere,” one can easily see how Amazon has been so successful.55

Individuals and students should also develop their own personal value propositions. Tell companies why they should hire you or why a graduate school should accept you. Show the value you bring to the situation. A value proposition will help you in different situations. Think about how your internship experience and/or study abroad experience may help a future employer. For example, explain to the employer the benefits and value of going abroad. Perhaps your study abroad experience helped you understand customers that buy from Company X and your customer service experience during your internship increased your ability to generate sales, which improved your employer’s profit margin. Thus, you may quickly contribute to Company X, something that they might very much value.

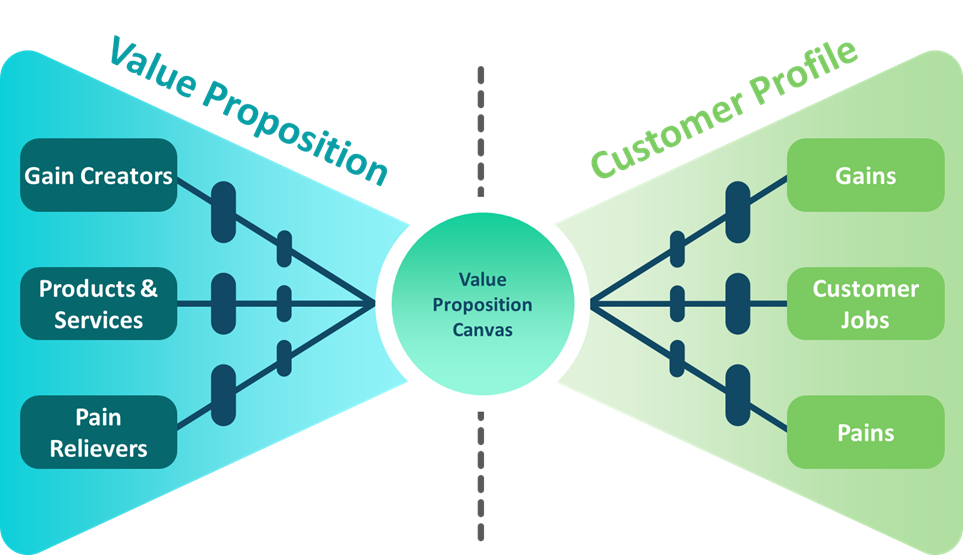

Value Proposition Canvas

The Value Proposition Canvas (see Figure below) is a tool focusing on what the customer values and needs regarding a product or service that was developed by Dr Alexander Osterwalder (link) explains:

Gain Creators: How can you improve the lives of your customers?

Pain Relievers: How can you help relieve customer barriers/issues?

Products & Services: What products or services can you offer to help customers satisfy a need, want, or desire?

Customer Jobs: What are your customers needs, wants, or desires (emotional and/or personal)?

Gains: How will your customers benefit? (Expectations, social benefits, functional, and financial gains).

Pains: Are your customers experiencing barriers to basic activities?

Figure 1. Value Proposition Canvas

SOURCE: Business Model Inc.

Video 1. Strategyzer’s Value Proposition Canvas Explained

Key Takeaways

A value proposition is a 30-second “elevator speech” stating the specific value a product or service provides for a target market. Firms may develop unique value propositions for distinct customers. The value proposition shows why the product or service is superior to competing offers and why the customer should buy it or why a firm should hire you.

Review Questions

- What is a value proposition?

- Create a value proposition and use it as your 30-second “elevator speech” to get the company interested in hiring you or talking to you more.

Effective Business Communication

Adapted from Business Communication for Success by the University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial–ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

SOURCE: Alex Andrews.

“Communication leads to community, that is, to understanding, intimacy and mutual valuing.”

- Rollo May

“I know that you believe that you understood what you think I said, but I am not sure you realize that what you heard is not what I meant.”

- Robert J. McCloskey

Communication is an activity, skill, and art that incorporates lessons learned across a wide spectrum of human knowledge. Perhaps the most time-honoured form of communication is storytelling. We have told each other stories for ages to help make sense of our world, anticipate the future, and certainly to entertain ourselves. The art of storytelling draws on your understanding of yourself, your message, and how you communicate it to an audience that is simultaneously communicating back to you. Your anticipation, reaction, and adaptation to the process will determine how successfully you can communicate. You were not born knowing how to write or even how to talk, but in growing up, you have undoubtedly learned how to (and not) tell a story out loud and in writing.

You did not learn to text in a day and did not learn all the codes from LOL (laugh out loud) to BRB (be right back) right away. In the same way, learning to communicate well requires you to read and study how others have expressed themselves, then adapt what you have learned to your present task—whether it is texting a brief message to a friend, presenting your qualifications in a job interview, or writing a business report. You come to this text with skills and an understanding that will provide a valuable foundation as we explore the communication process.

Effective communication takes preparation, practice, and persistence. There are many ways to learn communication skills; the school of experience, or “hard knocks,” is one of them. In the business environment, a “knock” (or lesson learned) may come at the expense of your credibility through a blown presentation. The classroom environment can offer you a trial run to try out new ideas and skills to communicate effectively, make a sale or form a new partnership. Listening to yourself, or perhaps the comments of others, may help you reflect on new ways to present, or perceive, thoughts, ideas, and concepts. The net result is your growth; ultimately your ability to communicate in business will improve, opening more doors than you might expect.

The degree to which you attend to each part will ultimately help give you the skills, confidence, and preparation to use communication in furthering your career.

Why Is It Important to Communicate Well?

Learning Objectives

Recognize the importance of communication in gaining a better understanding of yourself and others.

- Explain how communication skills help you solve problems, learn new things, and build your career.

Communication is key to your success, in relationships, workplace, as a citizen, and across your lifetime. Your ability to communicate comes from experience, which can be an effective teacher. You can learn from their lessons and be a more effective communicator.

Business communication can be a problem-solving activity to address:

- What is the situation?

- What are some communication strategies?

- What is the best course of action?

- What is the best way to design the chosen message?

- What is the best way to deliver the message?

In this book, we will examine this problem-solving process and help you learn to apply it in the kinds of situations you are likely to encounter over the course of your career.

Communication Influences Your Thinking

We all share a fundamental drive to communicate. We can define communication as understanding and sharing meaning (Pearson & Nelson, 2000). You share meaning in what you say and how you say it, both in oral and written forms. If you were unable to communicate, what would your life be like? A series of never-ending frustrations? Being unable to communicate might even mean losing a part of yourself, for you communicate your self-concept (your sense of self and awareness of who you are). Perhaps someone told you do not articulate, or your grammar needs improvement. Does that make you more or less likely to want to communicate? For some, it may be a positive challenge, while for others it may be discouraging. In all cases, your ability to communicate is central to your self-concept.

Look at your clothes, what are the brands you are wearing? What do you think they say about you? Do you feel that certain styles of shoes, jewellery, tattoos, music, or even automobiles express who you are? Part of your self-concept may be that you express yourself through texting, or through writing longer documents like essays and research papers, or through the way you speak. Your communications skills help you understand others, through their tone of voice, nonverbal gestures, or the format of written documents. These clues give insight about who they are and what their values and priorities may be. Active listening and reading are also part of being a successful communicator.

Communication Influences How You Learn

When you were an infant, you learned to talk over a period of months. When you got older, you did not learn to ride a bike, drive a car, or even text a message on your cell phone in one moment. You need to begin improving your speaking and writing with the frame of mind that it will require effort, persistence, and self-correction.

You learn to speak in public by first having conversations, then by answering questions and expressing your opinions in class, and finally by preparing and delivering a “stand-up” speech. Similarly, you learn to write by first learning to read, then by writing and learning to think critically. Your speaking and writing are reflections of your thoughts, experience, and education. Part of that combination is your level of experience listening to other speakers, reading documents and styles of writing, and studying formats like what you aim to produce.

As you study business communication, you may receive suggestions for improvement and clarification from speakers and writers more experienced than yourself. Take their suggestions as challenges to improve and do not give up when your first speech or draft does not communicate the message you intend. Stick with it until you get it right. Your success in communicating is a skill that applies to almost every field of work and enhances your relationships. Remember, luck is simply a combination of preparation and timing. You want to be prepared to communicate well when given the opportunity. Each time you do a good job, your success will bring more success.

Communication Represents You

You want to make a good first impression to convey a positive image. In your career, you will represent your business or company in spoken and written form. Your professionalism and attention to detail will reflect positively on you and set you up for success. In both oral and written situations, you will benefit from having the ability to communicate clearly. These are skills you will use for the rest of your life. Positive improvements in these skills will enrich your relationships, prospects for employment, and ability to make a difference.

Communication Skills Are Desirable

Employer surveys consistently ranked oral and written communication proficiencies in the top ten desirable skills year after year. In fact, high-powered business executives sometimes hire consultants to coach them in sharpening their communication skills. According to the National Association of Colleges and Employers, the following are the top five personal qualities or skills potential employers seek:

Communication skills (verbal and written)

Strong work ethic

Teamwork skills (works well with others, group communication)

Initiative

Analytical skills

Knowing this, you can see that one way for you to be successful and increase your promotion potential is to increase your abilities to speak and write effectively.

In September 2004, the National Commission on Writing for America’s Families, Schools, and Colleges published a study on 120 human resource directors finding that “writing is both a ‘marker’ of high-skill, high-wage, professional work and a ‘gatekeeper’ with clear equity implications,” said Bob Kerrey, chair of the commission. “People unable to express themselves clearly in writing limit their opportunities for professional, salaried employment” (The College Board, 2004). They estimate that over 40 million Americans are illiterate or unable to functionally read or write. If you are reading this book, you may not be part of an at risk group in need of basic skill development, but you still may need additional training and practice as you raise your skill level. An individual with excellent communication skills is an asset to every organization. No matter what career you plan to pursue, learning to express yourself professionally in speech and in writing will help you get there.

SOURCE: August de Richelieu. Effective communication skills are assets that will get you there.

Key Takeaways

Communication forms a part of your self-concept, and it helps you understand yourself and others, solve problems and learn new things, and build your career.

Exercises

Imagine that they have hired you to make “cold calls” to ask people whether they are familiar with a new restaurant that has just opened in your neighbourhood. Write a script for the phone call. Ask a classmate to co-present as you deliver the script orally in class, as if you were making a phone call to the classmate. Discuss your experience with the rest of the class.

Imagine you have been asked to create a job description. Identify a job, locate at least two sample job descriptions, and create one. Please present the job description to the class and note to what degree communication skills play a role in the tasks or duties you have included.

What Is Communication?

Learning Objectives

- Define communication and describe communication as a process.

- Identify and describe the eight essential components of communication.

- Identify and describe two models of communication.

We have proposed many theories to describe, predict, and understand the behaviours and phenomena of which communication consists. When communicating in business, we are often less interested in theory than in making sure our communications generate results. To achieve results, it is valuable to understand what communication is and how it works.

Defining Communication

The root of the word “communication” in Latin is communicare, which means to share, or to make common (Weekley, 1967). They define communication as understanding and sharing meaning (Pearson & Nelson, 2000). At the focal point of our study on communication is the relationship that involves interaction between participants. This definition serves us well with its emphasis on the process which we will examine in-depth across this text of coming to understand and share another’s point of view effectively.

Process is a dynamic activity where sequential actions to achieve a particular end (Pearson & Nelson, 2000). Imagine you are alone in your kitchen thinking and your mother enters to talk briefly. What has changed? Now, imagine someone else joins (you have not met before) and this stranger listens intently as you speak. Your perspective might change, and you might watch your words more closely. The feedback or response from your mother and the stranger (your audience) may cause you to re-evaluate what you are saying (factors influence communication).

Understanding: “To understand is to perceive, to interpret, and to relate our perception and interpretation to what we already know” (McLean, 2003). If a friend tells you a story about falling off a bike, what image comes to mind? Now your friend points out the window and you see a motorcycle lying on the ground. Understanding the words and the concepts or objects they refer to is an important part of the communication process.

Sharing means doing something together with one or more people, like compiling a report or resource, such as pizza. In communication, sharing occurs when you convey thoughts, feelings, ideas, or insights to others. You can also share with yourself (a process called intrapersonal communication) when you bring ideas to consciousness, ponder, or figure out the solution to a problem and have a classic “Aha!” moment when something becomes clear.

Meaning is what we share through communication. The word “bike” represents both a bicycle and a short name for a motorcycle. Using the context and use of meaning, we can discover and understand the message.

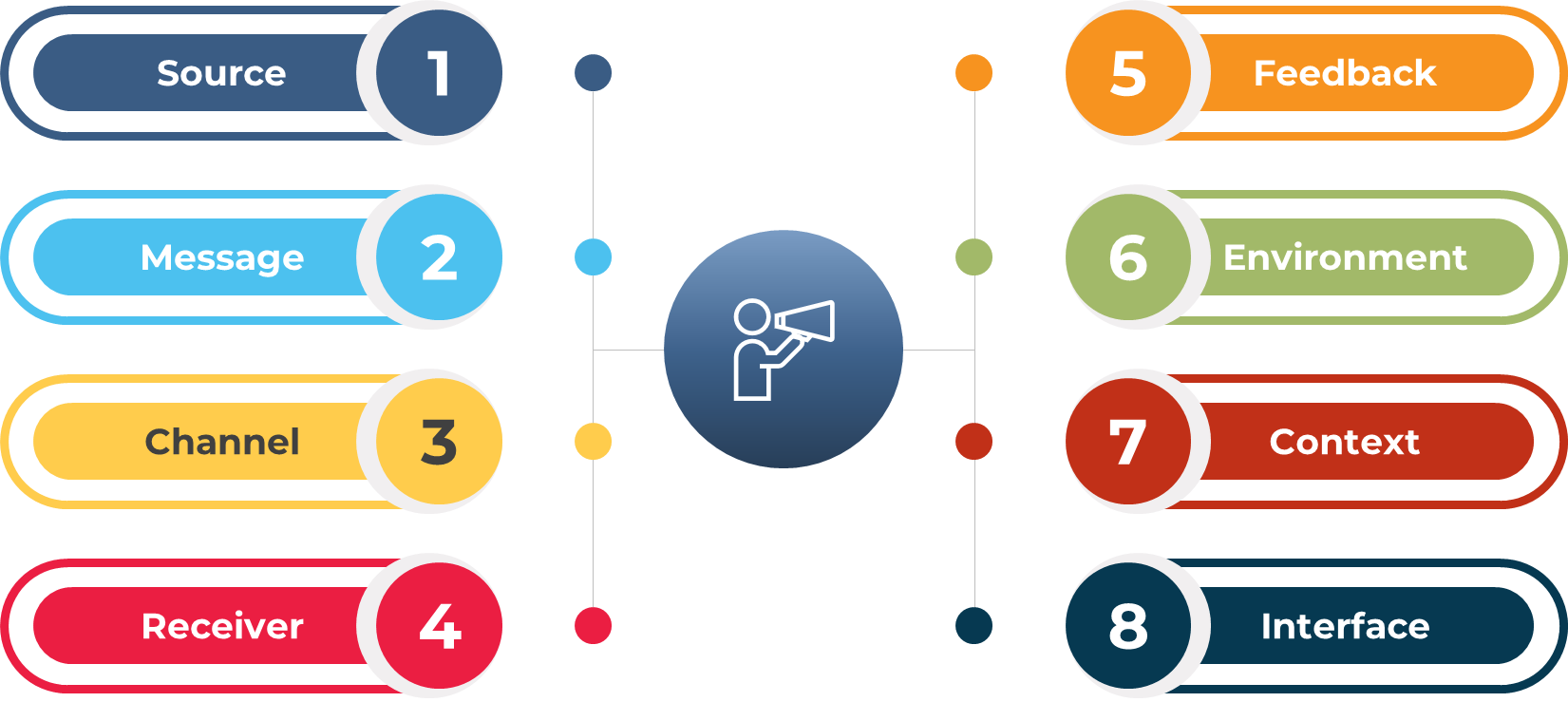

Eight Essential Components of Communication

To better understand the communication process, we can break it down into a series of eight essential components:

Figure 2. Communication Process

Each of these eight components serves an integral function in the overall process.

Source

The source imagines, creates, and sends the message. In a public speaking situation, the source is the person giving the speech. He or she conveys the message by sharing additional information with the audience. The speaker also conveys a message through his or her tone of voice, body language, and choice of clothing. The speaker begins by first determining the message – what to say and how to say it. The second step involves encoding the message by choosing just the right order or the perfect words to convey the intended meaning. The third step is to present or send the information to the receiver or audience. Finally, by watching for the audience’s reaction, the source perceives how well they received the message and responds with clarification or supporting information.

Message

“The message is the stimulus or meaning produced by the source for the receiver or audience” (McLean, 2005). When you plan to give a speech or write a report, your message may seem to be only the words you choose that will convey your meaning by using grammar and organization. You may choose to save your most important point for last. The message also comprises the way you say it (in a speech, with your tone of voice, your body language, and your appearance) and in a report, with your writing style, punctuation, and the headings and formatting you choose. Part of the message may be the environment or context you present it in and the noise that might make your message hard to hear or see.

Imagine, for example, that you are addressing a large audience of sales reps and are aware there is a World Series game tonight. Your audience might have a hard time settling down, but you may choose to open with, “I understand there is an important game tonight.” By expressing verbally something that most people in your audience are aware of and interested in, you might grasp and focus their attention.

Channel

“The channel is the way in which a message or messages travel between source and receiver” (McLean, 2005). For example, think of your television. How many channels do you have on your television? Each channel takes up some space (even in a digital world), in the cable or in the signal that brings the message of each channel to your home. Television combines an audio signal you hear with a visual signal you see. Together they convey the message to the receiver or audience. Turn off the volume on your television. Can you still understand what is happening? The body language conveys part of the message in the show. Now, turn up the volume but turn around so that you cannot see the television. You can still hear the dialogue and follow the story.

When you speak or write, you are using a channel to convey your message. Spoken channels include face-to-face conversations, speeches, telephone conversations, and voice mail messages, radio, public address systems, and voice over Internet protocol (VoIP). Written channels include letters, memorandums, purchase orders, invoices, newspaper, and magazine articles, blogs, email, text messages, tweets, and so forth.

Receiver

“The receiver receives the message from the source, analyzing and interpreting the message in ways both intended and unintended by the source” (McLean, 2005). To better understand this component, think of a receiver on a football team. The quarterback throws the football (message) to a receiver who must see and interpret where to catch the ball. The quarterback may intend for the receiver to “catch” his message in one way, but the receiver may see things differently and miss the football (the intended meaning) altogether.

As a receiver you listen, see, touch, smell, and/or taste to receive a message. Your audience “sizes you up,” much as you might check them out long before you take the stage or open your mouth. The nonverbal responses of your listeners can serve as clues on how to adjust your opening. By imagining yourself in their place, you expect what you would look for if you were them. Just as a quarterback plans where the receiver will be on the field to place the ball correctly, you too can recognize the interaction between source and receiver in a business communication context. All of this happens illustrating why and how communication is always changing.

Feedback

When you respond to the source, intentionally or unintentionally, you are giving feedback. Feedback are the messages the receiver sends back to the source. Verbal or nonverbal, all these feedback signals allow the source to see how well, how accurately (or how poorly and inaccurately) the message is received. Feedback also provides an opportunity for the receiver or audience to ask for clarification, to agree or disagree, or to show that the message can be more interesting. As the amount of feedback increases, the accuracy of communication also increases (Leavitt & Mueller, 1951).

For example, suppose you are a sales manager taking part in a conference call with four sales reps. As the source, you want to tell the reps to take advantage of the fact that it is World Series season to close sales on baseball-related sports gear. You state your message, but you hear no replies from your listeners. You might assume that this means they understood and agreed with you, but later in the month you might be disappointed with few sales. If you followed up your message with a request for feedback (“Does this make sense? Do any of you have questions?”) you might clarify your message, and to find out whether any of the sales reps believed your suggestion would not work with their customers.

Environment

“The environment is the atmosphere, physical and psychological, where you send and receive messages” (McLean, 2005). The environment can include physical attributes (i.e. tables, chairs, lighting, and sound equipment), room itself, and it can also include factors like formal dress (i.e. open and caring or more professional and formal). People may be more likely to have an intimate conversation when they are physically close to each other, and less likely when they can only see each other from across the room. In that case, they may text each other, itself an intimate form of communication that is influenced by the environment. Your environment (as a speaker) will impact and play a role in your speech. It is always a good idea to check out where you will speak before the day of the actual presentation.

Context

“The context of the communication interaction involves the setting, scene, and expectations of the individuals involved” (McLean, 2005). A professional communication context may involve business suits (environmental cues) that directly or indirectly influence expectations of language and behaviour among the participants.

A presentation or discussion does not take place as an isolated event. The degree to which the environment is formal or informal depends on the contextual expectations for communication held by the participants. The person sitting next to you may be used to informal communication with instructors, but this instructor may be used to verbal and nonverbal displays of respect in the academic environment. You may be used to formal interactions with instructors as well, and find your classmate’s question of “Hey Teacher, do we have homework today?” as rude and inconsiderate when they see it as normal. The nonverbal response from the instructor will certainly give you a clue about how they perceive the interaction, both the word choices and delivery.

SOURCE: Jopwell.

Context is all about what people expect from each other, and we often create those expectations out of environmental cues. Traditional gatherings like weddings or quinceañeras are often formal events. There is a time for quiet social greetings, a time for silence as the bride walks down the aisle, or the father may have the first dance with his daughter as she transforms from a girl to womanhood in the eyes of her community. In either celebration there may come a time for rambunctious celebration and dancing. You may give a toast, and the wedding or quinceañera context will influence your presentation, timing, and effectiveness.

In a business meeting, who speaks first? That probably has some relation to the position and role each person has outside the meeting. Context plays a very important role in communication, particularly across cultures.

Interference

Interference, also called noise, can come from any source. “Interference is anything that blocks or changes the source’s intended meaning of the message” (McLean, 2005). For example, if you drove a car to work or school, chances are you are surrounded by noise. Car horns, billboards, or perhaps the radio in your car interrupted your thoughts, or your conversation with a passenger.

Psychological noise happens when your thoughts occupy your attention while you are hearing, or reading, a message. Imagine that it is 4:45 p.m. and your boss, who is at a meeting in another city, emails you are asking for last month’s sales figures, an analysis of current sales projections, and the sales figures from the same month for the past five years. You may open the email, read, and think, “Great, no problem, I have those figures and that analysis right here in my computer.” You fire off a reply with last month’s sales figures and the current projections attached. Then, at five o’clock, you turn off your computer and go home. The next morning, your boss calls on the phone to tell you they are inconvenienced because you neglected to include the sales figures from the previous years. What was the problem? Interference: by thinking about how you wanted to respond to your boss’s message, you prevented yourself from reading attentively to understand the entire message.

Interference can come from other sources, too. Perhaps you are hungry, and your attention to your current situation interferes with your ability to listen. Maybe the office is hot and stuffy. If you were a member of an audience listening to an executive speech, how could this impact your ability to listen and take part?

Noise interferes with normal encoding and decoding of the message carried by the channel between source and receiver. Not all noise is bad, but noise interferes with the communication process. For example, your cell phone ringtone may be a welcome noise to you, but it may interrupt the communication process in class and bother your classmates.

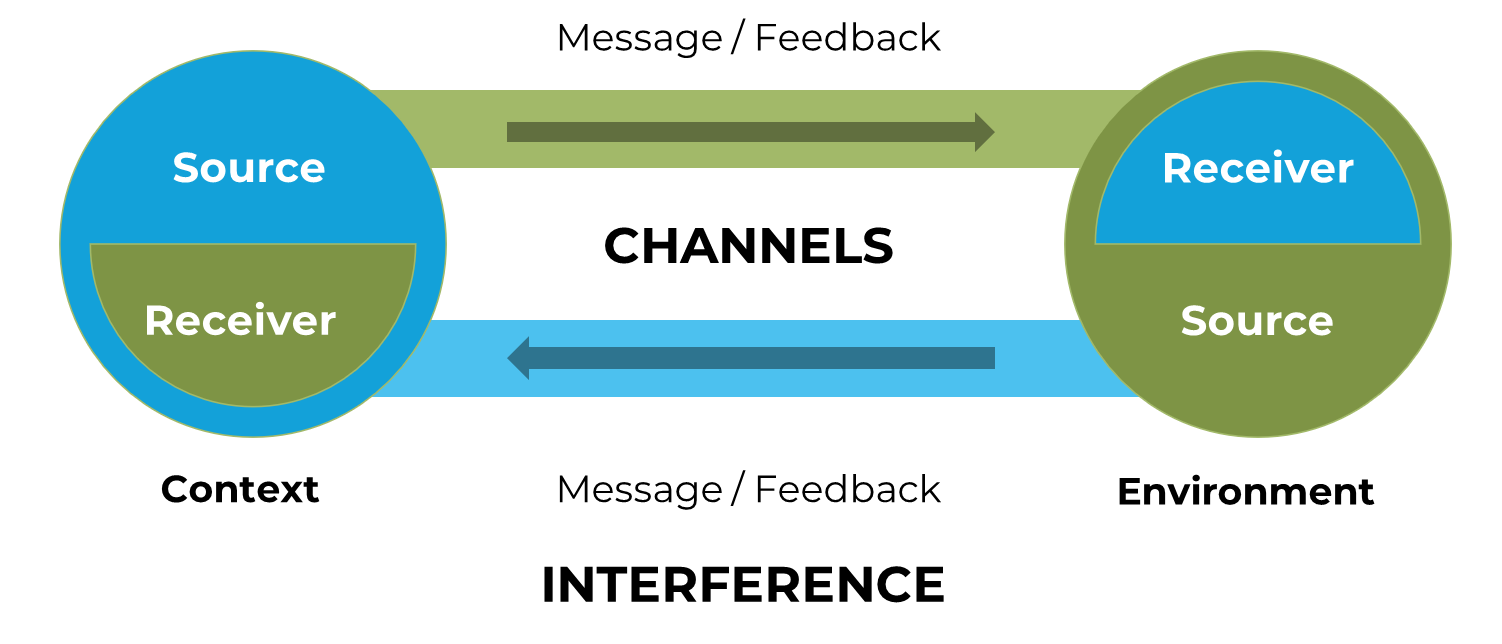

Two Models of Communication

Researchers have observed that when communication takes place, the source, and the receiver may send messages often overlapping. You, as the speaker, will often play both roles as source and receiver. You will focus on the communication and the reception of your messages to the audience. The audience will respond as feedback that will give you important clues. While there are many models of communication, here we will focus on two that offer perspectives and lessons for business communicators.

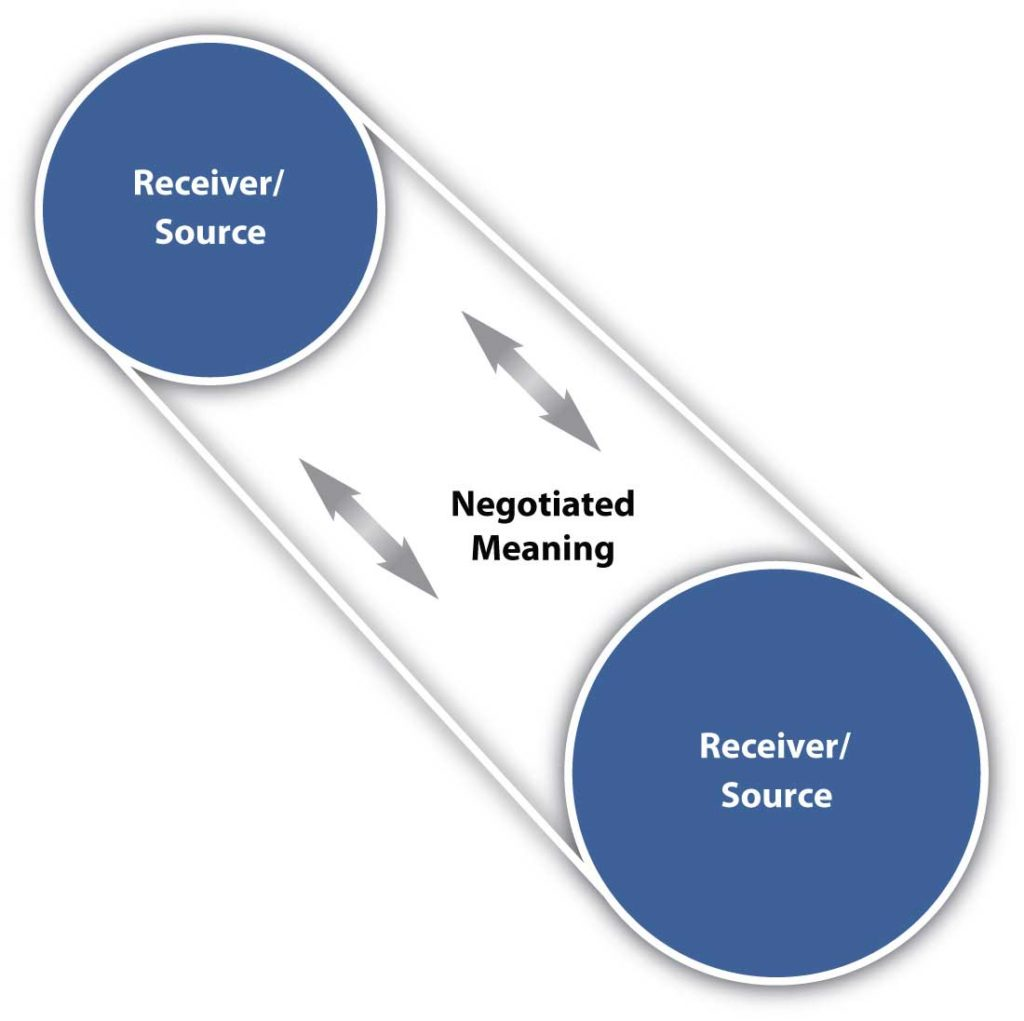

Rather than looking at the source sending a message and someone receiving it as two distinct acts, researchers often view communication as a transactional process (see Figure below “Transactional Model of Communication”), with actions often happening at the same time. The distinction between source and receiver is blurred in conversational turn-taking (i.e. where both participants play both roles simultaneously).

Figure 3. Transactional Model of Communication

Researchers have also examined the idea that we all construct our own interpretations of the message. As the State Department quote at the beginning of this chapter shows, what I said and what you heard may be different. In the constructivist model (see Figure below “Constructivist Model of Communication”), we focus on the negotiated meaning, or common ground, when trying to describe communication (Pearce & Cronen, 1980),

Imagine that you are visiting Atlanta, Georgia, and go to a restaurant for dinner. When asked if you want a “Coke,” you may reply, “sure.” The server may then ask you again, “what kind?” and you may reply, “Coke is fine.” They may ask a third time, “what kind of soft drink would you like?” In Atlanta, (the home of The Coca-Cola Company), they generically referred most soft drinks to as “Coke.” When you order a soft drink, you need to specify what type, even if you wish to order a beverage that is not a cola or not even made by the Coca-Cola Company. To someone from other regions of the United States, the words “pop,” “soda pop,” or “soda” may be the familiar way to refer to a soft drink; not necessarily the brand “Coke.” To communicate effectively, each person must realize what the term means for each other and establish common ground to understand the request and provide an answer.

Figure 4. Constructivist Model of Communication

Because we carry the multiple meanings of words, gestures, and ideas within us, we can use a dictionary to guide us, but we will still need to negotiate meaning.

Key Takeaways

The communication process involves understanding, sharing, and meaning, and it comprises eight essential elements: source, message, channel, receiver, feedback, environment, context, and interference. Among the models of communication are the transactional process, in which actions happen simultaneously, and the constructivist model, which focuses on shared meaning.

Exercises

- Draw what you think communication looks like. Share your drawing with your classmates.

- List three environmental cues and show how they influence your expectations for communication. Please share your results with your classmates.

- How does context influence your communication? Consider the language and culture people grew up with, and the role these play in communication styles.

- If you could design the perfect date, what activities, places, and/or environmental cues would you include to set the mood? Please share your results with your classmates.

- Observe two people talking. Describe their communication. See if you can find all eight components and provide an example for each one.

- What assumptions are present in the transactional model of communication? Find an example of a model of communication in your workplace or classroom and provide an example for all eight components.

Self-Understanding Is Fundamental to Communication

Learning Objectives

- Describe the factors that contribute to self-concept.

- Describe how the self-fulfilling prophecy works.

Understanding your perspective can lend insight to your awareness, the ability to be conscious of events and stimuli. Awareness determines what you pay attention to, how you carry out your intentions, and what you remember of your activities and experiences each day. Awareness is a complicated and fascinating area of study. The way we take in information, give it order, and assign it meaning has long interested researchers from disciplines including sociology, anthropology, and psychology.

Your perspective is a major factor in this dynamic process. If you are aware of it, you bring to the act of reading this sentence a frame of mind formed from experiences and education across your lifetime. Imagine that you see a presentation about snorkelling in beautiful Hawaii as part of a travel campaign. If you have never been snorkelling but love to swim, how will your perspective lead you to pay attention to the presentation? If, however, you had a traumatic experience as a child in a pool and are now afraid of being under water, how will your perspective influence your reaction?

Learning to recognize how your perspective influences your thoughts is a key step in understanding yourself and preparing to communicate with others.

SOURCE: Daniel Torobekov. Peaceful or dangerous? Your perception influences your response.

The communication process itself is the foundation for oral and written communication. Whether we express ourselves in terms of a live, face-to-face conversation or across a voice over Internet protocol (VoIP) chat via audio and visual channels, emoticons  , and abbreviations (IMHO [In My Humble Opinion]), the communication process remains the same. Imagine that you are at work and your Skype program makes the familiar noise showing that someone wants to talk. Your caller ID tells you it is a friend. You also know that you have the report right in front of you to get done before 5:00 p.m. Your friend is quite a talker, and for him everything has a “gotta talk about it right now” sense of urgency. You know a little about your potential audience or conversational partner. Do you take the call? Perhaps you chat back “Busy, after 5,” only to have him call again. You interpret the ring as his insistent need for attention, but you have priorities. You can choose to close the Skype program, stop the ringing, and get on with your report, but do you? Communication occurs on many levels in several ways.

, and abbreviations (IMHO [In My Humble Opinion]), the communication process remains the same. Imagine that you are at work and your Skype program makes the familiar noise showing that someone wants to talk. Your caller ID tells you it is a friend. You also know that you have the report right in front of you to get done before 5:00 p.m. Your friend is quite a talker, and for him everything has a “gotta talk about it right now” sense of urgency. You know a little about your potential audience or conversational partner. Do you take the call? Perhaps you chat back “Busy, after 5,” only to have him call again. You interpret the ring as his insistent need for attention, but you have priorities. You can choose to close the Skype program, stop the ringing, and get on with your report, but do you? Communication occurs on many levels in several ways.

Self-Concept

When we communicate, we are full of expectations, doubts, fears, and hopes. Where we place emphasis, what we focus on, and how we view our potential has a direct impact on our communication interactions. You gather a sense of self as you grow, age, and experience others and the world. At various times in your life, you have probably been praised and criticized, which may impact your confidence. We have learned much about ourselves through interacting with others. Not everyone has had positive influences in their lives, and not every critic knows what they are talking about, but criticism and praise still influence how and what we expect from ourselves.

SOURCE: Eternal Happiness.

Carol Dweck, a psychology researcher at Stanford University, states that “something that seems like a small intervention can have cascading effects on things we think of as stable or fixed, including extroversion, openness to new experience, and resilience.” (Begley, 2008) Your personality and expressions (i.e. oral and written communication) are thought to have a genetic component:

“More and more research is suggesting that, far from being simply encoded in the genes, much of personality is a flexible and dynamic thing that changes over the life span and is shaped by experience” (Begley, 2008).

If you were told by someone that you were not a good speaker, know this: You can change. You can shape your performance through experience, and a business communication course, a mentor at work, or even reading effective business communication authors can cause positive change.

Attitudes, Beliefs, and Values

When you consider what makes you, the answers multiply as do the questions. As a baby, you learned to recognize that the face in the mirror was your face. As an adult, you wonder what and who you are. Let us focus on self, which is defined as one’s own sense of individuality, motivations, and personal characteristics (McLean, 2003). We also must keep in mind that this concept is not absolute because it changes throughout our lifetimes.

One point of discussion useful for our study about ourselves as communicators is to examine our attitudes, beliefs, and values. These are all interrelated, and researchers have varying theories which comes first and which springs from another. We learn our values, beliefs, and attitudes through interaction with others. The Table below “Attitudes, Beliefs, and Values” defines these terms and provides an example of each.

Table 1. Attitudes, Beliefs, and Values

| Definition | Changeable? | Example | |

| Attitudes | Learned predispositions to a concept or object | Subject to change | I enjoyed the writing exercise in class today. |

| Beliefs | Convictions or expressions of confidence | Can change over time | This course is important because I may use the communication skills I am learning in my career. |

| Values | Ideals that guide our behaviour | Generally long-lasting | Effective communication is important. |

An attitude is your immediate disposition toward a concept or an object. Attitudes can change easily and frequently. You may prefer vanilla while someone else prefers peppermint, but if someone tries to persuade you of how delicious peppermint is, you may try it and find that you like it better.

Beliefs are ideas based on our previous experiences and convictions and may not have basis on logic or fact. You no doubt have beliefs on political, economic, and religious issues. These beliefs may not have formed through rigorous study, but you hold them as important aspects of self. Beliefs often serve as a frame of reference through which we interpret our world. Although they can change, it often takes time or sound evidence to persuade someone to change a belief.

SOURCE: Jennifer Enujiugha.

Values are core concepts and ideas of what we consider good or bad, right or wrong, or what is worth the sacrifice. Our values are central to our self-image, what makes us who we are. Like beliefs, we may not base our values on empirical research or rational thinking, but they are even more resistant to change than are beliefs. To undergo a change in values, a person may need to undergo a transformative life experience.

For example, suppose you highly value the freedom to make personal decisions, including the freedom to choose whether to wear a helmet while driving a motorcycle. This value of individual choice is central to your way of thinking, and you are unlikely to change this value. If your brother was driving a motorcycle without a helmet and suffered an accident that fractured his skull and left him with permanent brain damage, you might reconsider this value. While you might still value freedom of choice in many areas of life, you might become an advocate for helmet laws, and perhaps also for other forms of highway safety, such as stiffer penalties for texting while driving.

Self-Image and Self-Esteem

Your self-concept is two fundamental elements: self-image and self-esteem. Your self-image is how you see yourself, how you would describe yourself to others. It includes your physical characteristics (eye colour, hair length, height, and so forth). It also includes your knowledge, experience, interests, and relationships. In creating the personal inventory in this exercise, you identified many characteristics that contribute to your self-image. Image involves not just how you look, but also your expectations of yourself and what you can be.

What is your image of yourself as a communicator? How do you feel about your ability to communicate? While the two responses may be similar, they show different things. Your self-esteem is how you feel about yourself, your feelings of self-worth, self-acceptance, and self-respect. Healthy self-esteem can be important when you experience a setback or a failure. Instead of blaming yourself or thinking, “I’m just no good,” high self-esteem will enable you to persevere and give yourself positive messages like “If I prepare well and try harder, I can do better next time.”

Putting your self-image and self-esteem together yields your self-concept: your central identity and set of beliefs about who you are and what you can accomplish. When communicating, your self-concept can play an important part because you may struggle or feel talented and successful. Either way, if you view yourself as someone capable of learning new skills and improving as you go, you will have an easier time learning to be an effective communicator. Whether positive or negative, your self-concept influences your performance and the expression of that essential ability: communication.

Looking-Glass Self

Besides how we view ourselves and feel about ourselves, of course, we often take into consideration the opinions and behaviour of others. Charles Cooley’s looking-glass self reinforces how we look to others and how they view us, treat us, and interact with us to gain insight into our identity. We place an extra emphasis on parents, supervisors, and those who have some control over us when we look at others. Developing a sense of self as a communicator involves a balance between constructive feedback and constructive self-affirmation. You judge yourself, as others do, and both views count.

Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

Now, suppose that you are treated in an especially encouraging manner in one of your classes. Imagine that you have an instructor who continually “catches you doing something right” and praises you for your efforts and achievements. Would you be likely to do well in this class and perhaps take more advanced courses in this subject?

In a psychology experiment that has become famous through repeated trials, several public-school teachers were told that they expected specific students in their classes to do well because of their intelligence (Rosenthal & Jacobson, 1968). They identified these students as having special potential that had not yet “bloomed.” The teachers were unaware that these “special potential” students were randomly selected, and as a group, they had no more special potential than any other students.

Can you anticipate the outcome? As you may guess, the students lived up to their teachers’ level of expectation. Even though the teachers were supposed to give attention and encouragement to all students, in fact they unconsciously communicated special encouragement verbally and nonverbally to the special potential students. And these students, who were no more gifted than their peers, showed significant improvement by the end of the school year. This phenomenon came to be called the “Pygmalion effect” after the myth of a Greek sculptor named Pygmalion, who carved a marble statue of a woman so lifelike that he fell in love with her—and in response to his love she did in fact come to life and marry him (Rosenthal & Jacobson, 1968; Insel & Jacobson, 1975).

SOURCE: Cottonbro.

In more recent studies, researchers have observed that the opposite effect can also happen when students are lacking potential, teachers tend to discourage them or, at a minimum, cannot give them adequate encouragement. As a result, the students do poorly (Schugurensky, 2009; Anyon, 1980; Oakes, 1985; Sadker & Sadker, 1994).

When people encourage you, it affects the way you see yourself and your potential. Seek encouragement for your writing and speaking. Actively choose positive reinforcement as you develop your communication skills. You will make mistakes, but the important thing is to learn from them. Keep in mind that criticism should be constructive, with specific points you can address, correct, and improve.

The concept of a self-fulfilling prophecy, in which someone’s behaviour comes to match and mirror others’ expectations, is not new. Robert Rosenthal, a professor of social psychology at Harvard, has observed four principles while studying this interaction between expectations and performance:

- We form certain expectations of people or events.

- We communicate those expectations with various cues, verbal and nonverbal.

- People tend to respond to these cues by adjusting their behaviour to match the expectations.

- The outcome is that the original expectation becomes true.

Key Takeaways

You can become a more effective communicator by understanding yourself and how others view you: your attitudes, beliefs, and values; your self-concept; and how the self-fulfilling prophecy may influence your decisions.

Exercises

- How would you describe yourself as a public speaker? Now, five and ten years ago? Is your description the same or does it change across time? This business communication text and course can make a difference in what you might write for the category “year from today.”

- How does your self-concept influence your writing? Write a one- to two-page essay on this topic and discuss it with a classmate.

- Make a list of at least three of your strongly held beliefs. What are those beliefs based on? List some facts, respected authorities, or other evidence that support them. Share your results with your class.

- What are some values held by people, you know? Identify a target sample size (20 is a good number) and ask members of your family, friends, and peers about their values. Compare your results with those of your classmates.

- Make a list of traits you share with your family members. Interview them and see if anyone else in your family has shared them. Share and compare with your classmates.

- What does the field of psychology offer concern the self-fulfilling prophecy? Investigate the topic and share your findings.

Diverse Forms of Feedback

Learning Objectives

- Describe feedback as part of the writing process.

- Compare and contrast indirect and direct feedback.

- Understand internal and external feedback.

- Discuss diverse forms of feedback.

Just as you know that religion and politics are two subjects that often provoke emotional responses, you also recognize that once you are aware of someone’s viewpoint you can choose to not discuss certain topics or may change the way you address them. The awareness of bias and preference, combined with the ability to adapt the message before they send it, increases the probability of reception and successful communication. Until now we have focused on knowing the audience’s expectation and the assignment directions, as well as effective strategies for writing and production. Now, to complete the communication process, to close the writing process, we need to gather and evaluate feedback.

You may receive feedback from peers, colleagues, editors, or supervisors, but actual feedback from the intended audience can be rare. Imagine that you work in the marketing department of an engineering company and have written an article describing a new water pump that operates with little maintenance and less energy consumption than previous models. Your company has also developed an advertising campaign introducing this new pump to the market and has added it to their online sales menu. Once your article has been reviewed and posted, a reader may access it online in another country who is currently researching water pumps that fall within your product range. That reader will see a banner ad displayed across the header of the Web page, with the name of your company prominently displayed in the reader’s native language, even if your article is in English. These advertisements are contextually relevant ads. An example is Google’s Feedback Ad function, which incorporates the content of the site and any related search data to provide information to potential customers. If the reader found your article through the German version of Google, Google.de, the ad will display the Adwords, or text in an advertisement, in German.

As the author, you may never receive direct feedback on your article, but you may receive significant indirect feedback. Google can report the “hits” and links to your Web site, and your company’s information technology department can tell you about the hits on your Web site from Germany, where they originated, and whether the visitor started a sales order for the pump. If they left the sale incomplete, they know when the basket or order is abandoned or became inactive in the purchase process. If the sale was successful, your sales department can provide feedback as overall sales and information on specific customers. This allows you an opportunity for post-sales communication and additional feedback.

SOURCE: Supercreat.

The communication process depends on a series of components that are always present. If you remove one or more, the process disintegrates. You need a source and a receiver, even if those roles alternate and blur. This includes a message and a channel, or multiples of each in divergent ratios of signal strength and clarity, including the context and environment (including both the psychological expectations of the interaction and the physical aspects present). Interference is also part of any communication process. Because interference (internal or external) is always present, as a skilled business writer, you have learned how to understand and expect it so that you can get your message across to your audience.

The last step in the communication process is feedback. It contributes to the transactional relationship in communication and serves as part of the cycling and recycling of information, content, negotiations, relationships, and meaning between the source and receiver. Because feedback is so valuable to a business writer, you will welcome it and use strategies to overcome any interfering factors that may compromise reception and limit feedback.

Feedback is a receiver’s response to a source and can come in many forms. From the change in the cursor arrow as you pass over a link as a response to the reader’s sign, via the mouse, touch screen, or similar input device, as a nonverbal response, to one spoken out loud during a conversation, feedback is always present, even if we cannot capture the information.

Indirect Feedback

If you have worked in an office, you may have heard of the grapevine, and may already know it often carries whines instead of wine. The grapevine is the unofficial or informal communication network within an organization, and characterized by rumor, gossip, and innuendo. The grapevine often involves information that is indirect, speculative, and not immediately verifiable, making it unreliable but interesting.

In the same way, indirect feedback is a response that does not directly come from the receiver or source. The receiver may receive the message, and may become the source of the response, but they may not communicate that response directly to you, the author. Your ability to track who accesses your Web page, what they read, and how long their visit lasts can be a source of feedback that serves to guide your writing. You may also receive comments, emails, or information from individuals within your organization about what customers have told them; this is another source of indirect feedback. The information not being communicated directly may limit its use or reliability, but it has value (which all forms of feedback have).

Direct Feedback

You post an article about your company’s new water pump and when you come back to it an hour later there are 162 comments. As you scroll through the comments, you find that ten potential customers are interested in learning more, while the rest debate the specifications and technical abilities of the pump. This direct response to your writing is another form of feedback.

Direct feedback is a response that comes from the receiver. Direct feedback can be both verbal and nonverbal, and it may involve signs, symbols, words, or sounds that are unclear or difficult to understand. You may send an email to a customer who inquired about your water pump, offering to send a printed brochure and have a local sales representative call to evaluate how suitable your pump would be for the customer’s particular application. To do so, you will need the customer’s mailing address, physical location, and phone number. If the customer replies simply with “Thanks!” (no address, no phone number) how do you interpret this direct feedback? Communication is dynamic and complex, and it is no simple task to understand or predict. One aspect of the process, however, is predictable: feedback is always part of the communication process.

Just as nonverbal gestures do not appear independent of the context in which the communication interaction occurs, and often overlap, recycle, and repeat across the interaction, the ability to identify clear and direct feedback can be a significant challenge. In face-to-face communication, yawns, and frequent glances at the clock may serve as a clear signal (direct feedback) for lack of interest, but direct feedback for the writer is often less obvious. It is a rare moment when the article you wrote is read in your presence and direct feedback is immediately available (Often comes long after the publication).

SOURCE: Tumisu.

Internal Feedback

We usually think of feedback as something that can only come from others, but with internal feedback, we can get it from ourselves. The source generates internal feedback in response to the message created by that same source. You, as the author, will be key to the internal feedback process. This may involve reviewing your document before you send it or post it, but it also may involve evaluation from within your organization.

On the surface, it may appear that internal feedback cannot come from anyone other than the author, but that would be inaccurate. If we go back to the communication process and revisit the definitions of source and receiver, we can clearly see each undefined role by just one person or personality, but within the transactional nature of communication by function. The source creates, and the receiver receives. Once the communication interaction is started, the roles often alternate, as with an email or text message “conversation” where two people take turns writing.

When you write a document for a target audience (for instance, a group of farmers who will use the pumps your company produces to move water from source to crop) you will write with them in mind as the target receiver. Until they receive the message, the review process is internal to your organization, and feedback is from individuals and departments other than the intended receiver.

You may have your company’s engineering department confirm the technical specifications of the information you incorporated into the document, or have the sales department confirm a previous customer’s address. In each case, you as the author are receiving internal feedback about content you produced, and in some ways, each department is contributing to the message prior to delivery.

Internal feedback starts with you. Your review of what you write is critical. You are the first and last line of responsibility for your writing. As the author, it is your responsibility to ensure your content is: correct, clear, concise, ethical.

When an author considers whether the writing in a document is correct, it is important to interpret correctness broadly. The writing needs to be appropriate for the context of audience’s expectations and assignment directions. Some writing may be technically correct, even polished, and still be incorrect for the audience or the assignment. Attention to what you know about your reading audience (e.g., their reading levels and educational background) can help address the degree to which that you have written is correct for its designated audience and purpose.

Correctness also involves accuracy: questions concerning true, false, and somewhere in between. A skilled business writer verifies all sources for accuracy and sleeps well knowing that no critic can say his or her writing is inaccurate. If you allow less than information into your writing, you open the door to accusations of false information that could be a fraudulent act with legal ramifications. Keep notes on where and when you accessed Web sites, where you found the information, you cite or include, and prepare to back up your statements with a review of your sources.

Writing correctly also includes providing current, up-to-date information. Most business documents place an emphasis on the time-sensitivity of the information. It makes little sense to rely on sales figures (information that is outdated) from two years ago when you can use sales figures from last year. Information that is not current can serve useful purposes, but often requires qualification on why it is relevant in a current context.

Business writing also needs to be clear, otherwise it will fail in its purpose to inform or persuade readers. Unclear writing can lead to misunderstandings that consume time and effort to undo. An old saying in military communications is “Whatever can be misunderstood, will be misunderstood.” To give yourself valuable internal feedback about the clarity of your document, try to pretend you know nothing more about the subject than your least informed reader does. Can you follow the information provided? Are your points supported?

In the business environment, time is money, and bloated writing wastes time. The advice from the best-selling style guide by William Strunk Jr. and E. B. White to “omit needless words” is always worth bearing in mind.

SOURCE: Savvas Stavrinos.

Ethical consideration of the words you write, what they represent, and their consequences are part of the responsibility of a business writer. The writer offers information to a reading audience and losing credibility results in unlikely future interactions. Customer relationship management requires consideration of the context of the interaction, and all communication occurs with the context of community, whether that relationship is readily apparent. If the article is untruthful, this can negatively impact the brand management association and relationship with the product or services. Advertising may promote features, but false advertising can lead to litigation. The writer represents a business or organization, but also represents a family and a community. For a family or community to function, there must be a sense of trust amid the interdependence.

External Feedback

How do you know what you wrote was read and understood? Essentially, how do you know communication interaction has occurred? Writing, reading, and action based on the exchange of symbolic information reflects the communication process. Assessment of the feedback from the receiver is part of a writer’s responsibility. Increasingly Web-based documents allow for interaction and enhancement of feedback, but you will still produce documents that may exist as hard copies. Your documents may travel to places you do not expect and cannot predict. Feedback comes in many forms and in this part of our discussion we focus on answering that essential question, assessing interaction, and gathering information from it. External feedback involves a response from the receiver. Receivers become a source of information themselves. Attention to the channel they use (how they communicate feedback), as well as nonverbal aspects like time (when they send it), can serve you on this and future documents.

Hard Copy Documents and External Feedback

We will start this discussion with traditional, stand-alone hard copy documents in mind before we discuss electronic documents, including Web-based publications. Your business or organization may communicate in written forms across time zones and languages via electronic communication, but they still produce some documents on paper. Offline technology (i.e. copy machine, printer) are still the tools you use as a normal course of business.

Letters are a common way of introducing information to clients and customers, and someone may task you to produce a document that is printed and distributed via “snail mail,” or the traditional post mail services. Snail mail is a term that reflects the time delay associated with the physical production, packaging, and delivery of a document. Legal documents are still largely in hard copy print form. So too are documents that address the needs of customers and clients that do not, or prefer not to, access information electronically.

Age is one characteristic of an audience that may tempt to focus on when considering who may need to receive a letter in hard copy form, but you may be surprised about this. In a 2009 study of U.S. Internet use, the Pew Research Centre (Horrigan, 2009) found between 2008 and 2009, broadband Internet use by senior citizens increased from 20% to 30%, and broadband use by baby boomers (people born 1945–1963) increased from 50% to 61%.

Socioeconomic status is a better characteristic to focus on when considering hard copy documents. Lack of access to a computer and the Internet is a reality for most of the world’s population. It is often stated that half of the world’s population will never make a phone call in their lifetime, and even though the references for the claims are widespread and diverse, that there are people without access to a phone is striking for many Westerners. While cell phones are increasingly allowing poor and rural populations to skip the investment in landline networks and wireless Internet is a leapfrog technology that changes everything, cell phones, and computers are still prohibitively expensive for many.

Say you work for a major bank on the West Coast of the United States. We have assigned you to write a letter offering a refinance option to a select, previously screened audience composed of individuals who share several common characteristics: high-wage earners with exceptional credit scores. How will you best get the attention of this audience? If you emailed, it might get deleted as spam, or unwanted email that often lacks credibility and may even be dangerous. The audience is small, and you have a budget for hard copy production of documents that includes a line item for mailing costs. If the potential customer receives the letter from your department delivered by an overnight courier like FedEx, they may be more likely to receive your message.

In 2005, Wells Fargo Bank did exactly that. They mailed a letter of introduction outlining an opportunity to refinance at no cost to the consumer, targeting a group identified as high profit and low-risk. The channels selected (print-based documents on letterhead with the mode of delivery sure to get attention) prompted a response. The letter introduced the program, highlighted the features, and discussed why the customers were among a group of individuals for this offer (Diaz, 2005).

In the letter, the bank specifically solicited a customer response, feedback, via email and/or phone to establish dialogue. One could measure feedback in terms of response rate; in terms of verification of data on income, debt outstanding on loans, and current home appraisal values; and in terms of channel and how customers responded. All feedback has value to the author.

Hard copy documents can be a challenge for feedback, but that does not mean it is impossible to involve them in the feedback process. It’s important to remember that even in the late 1990s, most business documents were print-based. From sales reports to product development reports, they are printed, copied, bound, and distributed, all at considerable cost.

A purpose of your letter is to persuade the client or customer to reply by email or phone, one way to assess feedback is the response rate, or the number of replies in relation to the number of letters sent. If your report on a new product is prepared for internal use and targets a specific division within your company, their questions in relation to the document may serve as feedback. The memo can produce more questions and it should address in terms of policy, the negative feedback may highlight the need for revision. In each case, they often assess hard copy documents through oral and written feedback.

External Feedback in a Virtual Environment

Rather than focus on the dust on top of documents once produced, perhaps read, and sometimes forgotten, let us examine document feedback from the interactive world that gathers no dust. One challenge when the Web was young involved the accurate assessment of audience. Why is that relevant to a business writer? Because you produce content for a specific audience with a specific purpose, and the degree to which it is successful has some relation to its value. Imagine that you produced a pilot television program with all the best characters, excellent dialogue, and big-name stars portraying the characters, only to see the pilot flop. If you had all the right elements in a program, how could it fail? It failed to attract an audience. Television often uses ratings, or measurements of the estimated number of viewers, to measure success. Nielsen is the leading market research company associated with television ratings and online content. Programs that get past a pilot or past a first season do so because they have good ratings and ranked above other competing programs. All programs compete within a time slot or across a genre. Those that are highly ranked (receiving the largest number of viewers) can command higher budgets and often receive more advertising dollars.

Business writers experience a process of competition, ratings, feedback, and renewal within the world of online publishing. Business writers want their content to be read. Just as companies developed ways to measure the number of viewers of a television program, which led to rankings that influenced which programs survived and prospered and which were cancelled, the Web has a system of keeping track of what gets read and by whom. Perhaps you have heard of hits, as in how many hits a Web site receives, but have you stopped to consider what hits represent within our discussion of feedback?

First, let us examine what a hit is. When a browser, like Internet Explorer or Firefox, receives a file from a Web server, they consider it a hit. They may keep your document on the company’s Web server, or a computer dedicated to serving the online requests for information via the Internet. The Web server receives a request from the user and sends the files associated with the page; every Web page contains several files including graphics, images, and text. Each file request and receipt between server and browser counts as a hit, regardless of how many files each page contains. If you created an online sales catalogue with 20 images per page, 20 boxed text descriptions, and all the files for indicating colour, size, and quantity, your document could have quite a few hits with just one page request and only one viewer.

Do many hits on your document mean it was successful? Not necessarily. They have largely discredited hits or page views as a reliable measure of a document’s effectiveness, popularity, or audience size. In fact, the word “hits” is sometimes humorously referred to as being the acronym for how idiots track success. Page views are a count of how many times they viewed a Web page, irrespective of the number of files it contains. Each time a user or reader views the page counts as one page view.

SOURCE: Szfphy.

Nielsen Online and Source.com are two companies that provide Web traffic rating services, and Google has also developed services to better enable advertisers to target specific audiences. They commonly track the number of unique visits a reader makes to a Web site, and use cookies, or small, time-encoded files that identify specific users, to generate data.

Another way to see whether they have read a document online is to present part of the article with a “reveal full article” button after a couple of paragraphs. If someone wants to read the entire article, the button needs to be clicked to display the rest of the content. Because this feature can annoy readers, many content providers also display a “turn off reveal full article” button to provide an alternative; Yahoo! News is an example of a site that gives readers this option.

Jon Kleinberg’s HITS (hyperlink-induced topic search) algorithm has become a popular and more effective way to rate Web pages (Kleinberg, 1998). HITS ranks documents by the links within the document, presuming that a good document is one that incorporates and references, providing links to, other Web documents while also being frequently cited by other documents. Hubs, or documents with many links, in relation to authority pages, or frequently cited documents. This relationship of hubs and authority is mutually reinforcing, and if you can imagine a Web universe of 100 pages, the one with the most links and which is most frequently referred to wins.

As a business writer you will naturally want to incorporate authoritative sources and relevant content, but you will also want to attract and engage your audience, positioning your document as hub and authority within that universe. Feedback as links and references may be one way to assess your online document.

User-Generated Feedback

Moving beyond the Web tracking aspects of feedback measurement in terms of use, let us examine user-generated responses to your document. Say you have reviewed the posts left by unique users to the comments section of the article. In some ways, this serves the same purpose as letters to the editor in traditional media. In newspapers, magazines, and other offline forms of print media, they produce an edition with a collection of content and then delivered to an audience. The audience includes members of a subscriber-based group with common interests, as well as those who read a magazine casually while waiting in the doctor’s office. If an article generated interest, enjoyment, or outrage (or demanded correction), people would write letters in response to the content. They would publish select responses in the next edition. There is a time delay associated with this system that reflects the preparation, production, and distribution cycle of the medium. If they publish the magazine once a month, it takes a full month for user feedback to be presented in print. For example, letters commenting on an article in the March issue would appear in the “Letters” section of the May issue.

Public relations announcements, product reviews, and performance data of your organization are available internally or externally via electronic communication. If you see a factual error in an article released internally, within minutes you may respond with an email and a file attachment with a document that corrects the data. In the same way, if the document is released externally, you can expect that feedback from outside your organization will be quick. Audience members may debate your description of the water pump, or openly question its effectiveness in relation to its specifications; they may even post positive comments. Customer comments, like letters to the editor, can be a valuable source of feedback.

Customer reviews and similar forms of user-generated content are increasingly common across the Internet. They often choose written communication as the preferred format; from tweets to blogs and commentary pages, to threaded, theme-based forums, person-to-person exchange is increasingly common. Still, as a business writer, you note that even with the explosion of opinion content, the tendency for online writers to cite a Web page with a link can promote interaction.

It may sound strange to ask this question, but is all communication interaction good? Let us examine examples of interaction and feedback and see if we can arrive at an answer.

You may have heard that one angry customer can influence several future customers, but negative customer reviews in the online information age can make a disproportionate impact in a relatively short time. While the online environment can be both fast and effective in terms of distribution and immediate feedback, it can also be quite ineffective, depending on the context. “Putting ads in front of Facebook users is like hanging out at a party and interrupting conversations to hawk merchandise,” according to Newsweek journalist Daniel Lyons. Relationships between users, sometimes called social graphs, reflect the dynamic process of communication, and they hold value, but translating that value into sales can be a significant challenge.

Overall, as we have seen, your goal as a business writer is to meet the audience and employer’s expectations concisely. Getting your content to a hub position, and including authoritative references, is a great way to make your content more relevant to your readers. Trying to facilitate endless discussions may engage and generate feedback but may not translate into success. Facebook serves as a reminder that you want to provide solid content and attend to the feedback. People who use Google already have something in mind when they perform a search, and if your content provides what readers are looking for, you may see your page views and effectiveness increase.

Interviews

Interviews provide an author with the opportunity to ask questions of, and receive responses from, audience members. Since interviews take considerable time and cannot easily scale up to address large numbers of readers, they are most often conducted with a small, limited audience. An interview involves an interviewer, and interviewee, and a series of questions. It can be an employment interview, or an informational interview in preparation of document production, but in this case, we are looking for feedback. As a business writer, you may choose to schedule time with a supervisor to ask a couple of questions about how the document you produced could improve. You may also schedule time with the client or potential customer and try to learn more. You may interact across a wide range of channels, from face-to-face to an email exchange, and learn more about how your document is received. Take care not to interrupt the interviewee, even if there is a long pause, as some of the best information comes up when people feel the need to fill the silence. Be patient and understanding and thank them for taking the time to take part in the interview. We build relationships over time and the relationship you build through a customer interview, for example, may have a positive impact on your next writing project.

Surveys

At some point, you may have answered your phone to find a stranger on the other end asking you to take part in a survey for a polling organization like Gallup, Pew, or Roper. You may have also received a consumer survey in the mail, with a paper form to fill out and return in a postage-paid envelope. Online surveys are also becoming increasingly popular. For example, SurveyMonkey.com is an online survey tool that allows people to respond to a set of questions and provide responses. This type of reader feedback can be valuable, particularly if some questions are open-ended. Closed questions require a simple yes or no to respond, making them easier to tabulate as “votes” but open-ended questions give respondents complete freedom to write their thoughts. They promote the expression of new and creative ideas and can lead to valuable insights for you, the writer.

Surveys can take place in person in an interview format, and this format is common when taking a census. For example, the U.S. government employs people for a short time to go door to door for a census count of everyone. Your organization may lack comparable resources and may choose to mail out surveys on paper with postage-paid response envelopes or may reduce the cost and increase speed by asking respondents to complete the survey online.

Focus Groups