Main Body

10 10/ Teams

Adapted from Fundamentals of Business: Canadian Edition by Pamplin College of Business and Virginia Tech Libraries is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial–ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Source: Anna Shvets .

Teamwork in Business

Learning Objectives

- Define different teams and describe key characteristics.

- Explain why organizations use teams.

- Identify factors that contribute to team cohesion or division.

- Describe the importance of learning to take part in team-based activities.

- Identify the skills needed by team members and the roles that members of a team might play.

- Explain the skills and behaviours that foster effective team leadership.

What Is a Team? How Does Teamwork Work?

A team (or a work team) is a group of people with complementary skills who work together to achieve a specific goal.86

Teams Versus Groups

Teams are organized around a shared aim, something to accomplish.

“Teamwork is the ability to work together toward a common vision. The ability to direct individual accomplishments toward organizational objectives. It is the fuel that allows common people to attain uncommon results.”

– Andrew Carnegie

A group is distinct. A group of department store managers, for example, might meet monthly to discuss their progress in cutting plant costs. However, each manager is focused on the goals of his or her department because each is held accountable for meeting those goals.

Some Key Characteristics of Teams

To put teams in perspective, let us identify five key characteristics:87

Share accountability for achieving specific common goals.

Function interdependently.

Require stability.

Hold authority and decision-making power.

Operate in a social context.

Why Organizations Build Teams

Why do major organizations now rely so much on teams to improve operations? Executives at Xerox have reported that team-based operations are 30% more productive than conventional operations. General Mills says that factories organized around team activities are 40% more productive than traditionally organized factories. FedEx says that teams reduced service errors (lost packages, incorrect bills) by 13% in the first year.88

Today teams can address a variety of challenges in the world of corporate activity. Before we go any further, however, we should remind ourselves that the data we have just cited are not necessarily definitive. They may not be the aim, companies are more likely to report successes than failures. Teams do not always work. According to one study, team-based projects fail 50% to 70% of the time.89

The Effect of Teams on Performance

SOURCE: Sebastian Voortman.

Research shows that companies build and support teams because of their effect on overall workplace performance, both organizational and individual. If we examine the impact of team-based operations according to a wide range of relevant criteria, we find that overall organizational performance generally improves. The following figure lists several areas in which we can analyze workplace performance and shows the percentage of companies that have reported improvements in each area.

Table 1. Overall Workplace Performance

|

Area of Performance |

Firms Reporting Improvement |

|

Product and service quality |

70% |

|

Customer service |

67% |

|

Worker satisfaction |

66% |

|

Quality of worklife |

63% |

|

Productivity |

61% |

|

Competitiveness |

50% |

|

Profitability |

45% |

|

Absenteeism | turnover |

23% |

Adapted from Lawler, E. E., Mohaman, S. A., & Ledford, G. E. (1992). Creating high performance organizations: Practices and results of employee involvement and total quality in Fortune 1000 Companies. San Francisco: Wiley.

Types of Teams

Teams can improve company and individual performance in several areas. Not all teams, however, are formed to achieve the same goals or charged with the same responsibilities. Nor are they organized in the same way. Some, for instance, are more autonomous than others, less accountable to those higher in the organization. Some depend on a team leader who defines the team’s goals and making sure that its activities are performed effectively. Others are self-governing: though a leader lays out overall goals and strategies, the team itself chooses and manages the methods by which it pursues its goals and implements its strategies.90 Teams also vary according to their membership. Let us look at several categories of teams.

Manager-Led Teams

As its name implies, in the manager-led team the manager is the team leader and oversees setting team goals, assigning tasks, and monitoring the team’s performance. The individual team members have relatively little autonomy. For example, the key employees of a professional football team (a manager-led team) are highly trained (and highly paid) athletes, but their activities on the field are tightly controlled by a head coach. As team manager, the coach is responsible both for developing the strategies by which the team pursues its goal of winning games and for the outcome of each game and season. They are also solely responsible for interacting with managers above them in the organization. The players mainly execute plays. This hierarchy is consistent in organizations such as firefighting, policing, military, and medicine.91

SOURCE: Pixabay.

Self-Managing Teams

Self-managing teams (also known as self-directed teams) have considerable autonomy. They are usually small and often absorb activities that were once performed by traditional supervisors. A manager or team leader may determine overall goals, but the members of the self-managing team control the activities needed to achieve those goals.

Self-managing teams are the organizational hallmark of Whole Foods Market, the largest natural-foods grocer in the United States. Each store is run by ten departmental teams, and virtually every store employee is a member of a team. Each team has a designated leader and its own performance targets. (Team leaders also belong to a store team, and store team leaders belong to a regional team.) To do its job, every team has access to the information, including sales and even salary figures that most companies reserve for traditional managers.92

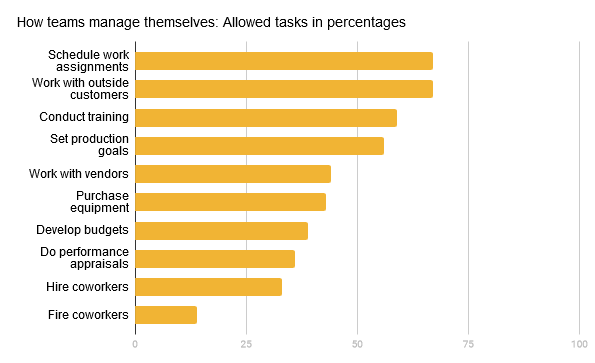

Not every self-managed team enjoys the same autonomy. Companies vary widely in choosing which tasks teams can manage and which ones are best left to upper-level management only. As you can see, self-managing teams are often allowed to schedule assignments, but they are rarely allowed to fire coworkers.

Figure 1. How Teams Manage Themselves

Cross-Functional Teams

Many companies use cross-functional teams that cut across an organization’s functional areas (operations, marketing, finance, and so on). A cross-functional team takes advantage of the special expertise of members drawn from different functional areas of the company. When the Internal Revenue Service, for example, wanted to study the effects on employees of a major change in information systems, it created a cross-functional team composed of people from a wide range of departments. The final study reflected expertise in such areas as job analysis, training, change management, industrial psychology, and ergonomics.93

Cross-functional teams figure prominently in the product development process at Nike, where they take advantage of expertise from both inside and outside the company.

SOURCE: Fauxels.

Typically, team members include not only product designers, marketing specialists, and accountants but also sports-research experts, coaches, athletes, and even consumers. Nike’s team was a cross-functional team; responsibility for developing the new product is not passed along from the design team to the engineering team but entrusted to a special team composed of both designers and engineers.

Committees and task forces, both of which are dedicated to specific issues or tasks, are often cross-functional teams. Problem-solving teams, which study such issues as improving quality or reducing waste, may be intradepartmental or cross-functional.94

Virtual Teams

SOURCE: Olha Ruskykh.

Technology now makes it possible for teams to function not only across organizational boundaries like functional areas but also across time and space. Technologies such as videoconferencing allow people to interact simultaneously and in actual time, offering several advantages in conducting the business of a virtual team.95 Members can take part from any location or time of day, and teams can “meet” for as long as it takes to achieve a goal or solve a problem, a few days, weeks, or months.

Team size does not seem to be an obstacle with virtual team meetings; in building the F-35 Strike Fighter, U.S. defence contractor Lockheed Martin staked the $225 billion project on a virtual product-team of unprecedented global dimension, drawing on designers and engineers from the ranks of eight international partners from Canada, the United Kingdom, Norway, and Turkey.96

Why Teamwork Works

Now that we know a bit about how teams work, we need to ask ourselves why they work. This is a complex issue. In this section, we’ll explore why teams are often effective and when they are ineffective.

Factors in Effective Teamwork

Let us begin by identifying several factors that contribute to effective teamwork. Teams are most effective when the following factors are met:

Members communicate effectively.

Members depend on each other. When team members rely on each other to get the job done, team productivity and efficiency tend to be high.

Members trust one another.

Members work better together than individually. When team members perform better as a group than alone, collective performance exceeds individual performance.

Members become boosters. When each member is encouraged by other team members to do his or her best, collective results improve.

Team members enjoy being on the team.

Leadership rotates.

Some of these factors may seem intuitive. Because such issues are rarely clear-cut, we need to examine group effectiveness from another perspective, one that considers the effects of factors that are not so straightforward.

Group Cohesiveness

The idea of group cohesiveness refers to the attractiveness of a team to its members. If a group is high in cohesiveness, membership is quite satisfying to its members. If it is low in cohesiveness, members are unhappy with it and may try to leave it.97

SOURCE: Designecologist.

What Makes a Team Cohesive?

Many factors may contribute to team cohesiveness, but in this section, we will focus on five of the most important:

Size. The bigger the team, the less satisfied members tend to be. When teams get too large, members find it harder to interact closely with other members; a few members tend to dominate team activities, and conflict becomes more likely.

Similarity. People usually get along better with people like themselves, and teams are generally more cohesive when members perceive fellow members as people who share their own attitudes and experience.

Success. When teams are successful, members are satisfied, and other people are more likely to be attracted to their teams.

Exclusiveness. The harder it is to get into a group, the happier the people who are already in it. Team status also increases members’ satisfaction.

Competition. Membership is valued more highly when there is motivation to achieve common goals and outperform other teams.

Maintaining team focus on broad organizational goals is crucial. If members get too wrapped up in immediate team goals, the entire team may lose sight of the larger organizational goals toward which it’s supposed to be working. Let us look at some factors that can erode team performance.

Groupthink

It is easy for leaders to direct members toward team goals when members are all on the same page, when there is a basic willingness to conform to the team’s rules. When there is too much conformity, however, the group can become ineffective: it may resist fresh ideas and, what is worse, may end up adopting its own dysfunctional tendencies as its way of doing things. Such tendencies may also encourage a phenomenon known as groupthink, the tendency to conform to group pressure in decisions, while failing to think critically or to consider outside influences.

Groupthink is often cited as a factor in the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger in January 1986: engineers from a supplier of components for the rocket booster warned that the launch might be risky because of the weather but were persuaded to set aside their warning by NASA officials who wanted the launch to proceed as scheduled.98

SOURCE: Nataliya.

Motivation and Frustration

Remember that teams are composed of people, and whatever the roles they are playing at a time, people are subject to psychological difficulties. As members of workplace teams, they need motivation, and when motivation is low, so are effectiveness and productivity. The difficulty of maintaining a high-level of motivation is the chief cause of frustration among members of teams. It is also a chief cause of ineffective teamwork, and that is one reason more employers now look for the ability to develop and sustain motivation when they’re hiring new managers.99

Other Factors that Erode Performance

Let us take a quick look at three other obstacles to success in introducing teams into an organization:100

Unwillingness to cooperate. Failure to cooperate can occur when members do not or will not commit to a common goal or set of activities. What if, for example, half the members of a product development team want to create a brand-new product and half want to improve an existing product? The entire team may get stuck on this point of contention for weeks or even months. Lack of cooperation between teams can also be problematic to an organization.

Lack of managerial support. Every team requires organizational resources to achieve its goals, and if management is not willing to commit the needed resources (i.e. funding or key personnel) a team will probably fall short of those goals.

Failure of managers to delegate authority. Team leaders are often chosen from the ranks of successful supervisors, first-line managers give instructions on a day-to-day basis and expect to have them carried out. This approach to workplace activities may not work very well in leading a team, a position in which success depends on building a consensus and letting people make their own decisions.

The Team and Its Members

SOURCE: SplitShire.

“I’ll work extra hard and do it myself, but please don’t make me have to work in a group.”

Like it or not, you’ve probably already notice that you will have team-based assignments in college. Over 66% of all students’ report having taken part in the work of an organized team, and if you are in business school, you will almost certainly find yourself engaged in team-based activities.101

Why do we put so much emphasis on something that, reportedly, makes many students feel anxious and academically drained? Here is one college student’s practical-minded answer to this question:

“In the real world, you have to work with people. You don’t always know the people you work with, and you don’t always get along with them. Your boss won’t particularly care, and if you can’t get the job done, your job may end up on the line. Life is all about group work, whether we like it or not. And school, in many ways, prepares us for life, including working with others.”102

She is right. Placing so much emphasis on teamwork skills and experience, business colleges are doing the responsible thing like preparing students for the business world. A survey of Fortune 1000 companies reveals that 79% use self-managing teams and 91% use other forms of employee work groups. Another survey found that the skill that most employers value in new employees is the ability to work in teams.103 Consider the advice of former Chrysler Chairperson Lee Iacocca: “A major reason that capable people fail to advance is that they don’t work well with their colleagues”.104 The importance of the ability to work in teams was confirmed in a survey of leadership practices of over 60 of the world’s top organizations.105

When top executives in these organizations were asked what causes the careers of high-potential leadership candidates to derail, 60% of the organizations cited “inability to work in teams.” Interestingly, only 9% attributed failing to advance was a “lacking technical ability.” To put it in plain terms, the question is not whether you will work as part of a team. You will. The question is whether you will know how to take part successfully in team-based activities.

Will You Make a Good Team Member?

What if your instructor divides the class into teams and assigns each team to develop a new product plus a business plan to get it on the market? What teamwork skills could you bring to the table, and what teamwork skills do you need to improve? Do you possess qualities that might make you an excellent team leader?

What Skills Does the Team Need?

Sometimes we hear about a sports team made up of mostly average players who win a championship because of coaching genius, flawless teamwork, and superhuman determination.106 But not terribly often. In fact, we usually hear about such teams simply because they are newsworthy exceptions to the rule. Typically, a team performs well because its members possess some level of talent.

A team can succeed only if its members provide the skills that need managing, which requires some mixture of four sets of skills:

Communication Skills. Because how you communicate can positively and negatively affect relationships within the team and outside the team with managers, customers, vendors, etc.

Technical skills. Because teams must perform certain tasks, they need people with the skills to perform them. For example, if your project calls for a lot of math work, it is good to have someone with the necessary quantitative skills.

Decision-making and problem-solving skills. Because every task is subject to problems, and because handling every problem means deciding on the best solution, it is good to have members who are skilled in identifying problems, evaluating alternative solutions, and deciding on the best options.

Interpersonal skills. Because teams need direction and motivation and depend on communication, every group benefits from members who know how to listen, provide feedback, and resolve conflict. Some members must also be good at communicating the team’s goals and needs to outsiders.

The key is ultimately to have the right mix of these skills. Remember, too, that no team needs to possess all these skills from day one. Most times, a team gains certain skills only when members volunteer for certain tasks and perfect their skills in performing them. For the same reason, effective teamwork develops over time as team members learn how to handle various team-based tasks. Teamwork is always a work in progress.

What Roles Do Team Members Play?

As a student and later in the workplace, you will be a member of a team more often than a leader. Team members can have as much impact on a team’s success as its leaders. A key is the quality of the contributions they make in performing non-leadership roles.107

What, exactly, are those roles? You have probably concluded that every team faces two basic challenges:

Accomplishing its assigned task

Maintaining or improving group cohesiveness

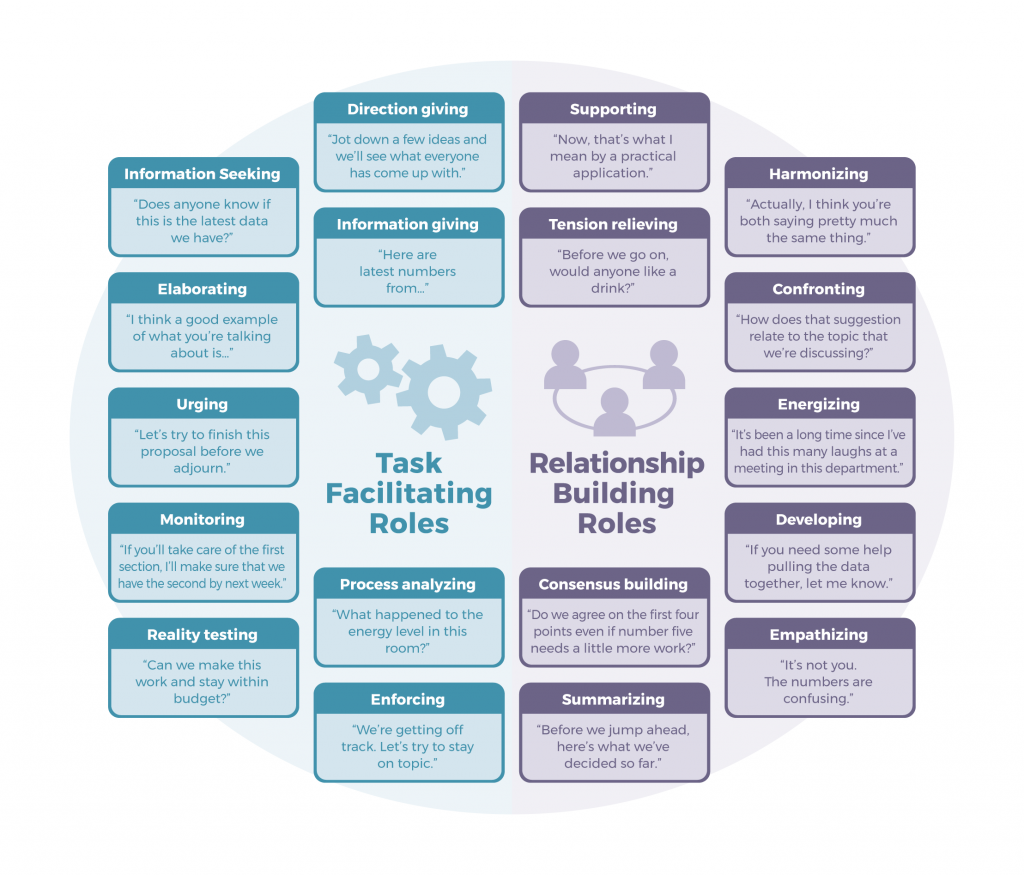

Whether you affect the team’s work positively or negatively depends on the extent to which you help it or hinder it in meeting these two challenges.108 We can divide teamwork roles into two categories, (task-facilitating roles and relationship-building roles) see Figure above (link).

Task-Facilitating Roles

Task-facilitating roles address the critical challenge of accomplishing the team goals. As you can see from Table P.6, such roles include not only providing information when someone else needs it but also asking for it when you need it. In addition, it includes monitoring (checking on progress) and enforcing (making sure that team decisions are carried out). Task facilitators are especially valuable when assignments are not clear or when progress is too slow.

SOURCE: Ron Lach.

Relationship-Building Roles

When you challenge unmotivated behaviour or help other team members understand their roles, you are performing a relationship-building role and addressing the second challenge of maintaining or improving group cohesiveness. This type of role includes activities that improve team “chemistry,” from empathizing to confronting.

Remember three points about this model:

- Teams are most effective when there is a good balance between task facilitation and relationship-building.

- It is hard for any member to perform both types of roles, as some people are better at focusing on tasks and others on relationships.

- Overplaying any facet of any role can easily become counterproductive. For example, elabourating on something may not be the best strategy when the team needs to make a quick decision; and consensus building may cause the team to overlook an important difference of opinion.

Blocking Roles

Finally, show what you know to block behaviours and the tactics used when someone is using the behaviour. So-called blocking roles comprise behaviour that inhibits either team performance or that of individual members. Every member of the team should know how to recognize blocking behaviour. If teams do not confront dysfunctional members, they can destroy morale, hamper consensus building, create conflict, and hinder progress.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: link.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: link.

Class Team Projects

In your academic career you will take part in several team projects. To get insider advice on how to succeed on team projects in college, let us look at some suggestions offered by students from their experience.109

Draw up a team charter. At the beginning of the project, draw up a team charter that includes: the goals of the group; ways to ensure that each team member’s ideas are considered; timing and frequency of meeting. A more informal way to arrive at a team charter is to set some ground rules to which everyone agrees. Your instructor may also require you to sign an existing team contract or charter like the one below.

Contribute your ideas. Share your ideas with your group. The worst that could happen is that they will not be used (which is what would happen if you kept quiet).

Never miss a meeting or deadline. Pick a weekly meeting time and write it into your schedule as if it were a class. Never skip it.

Be considerate of each other. Be patient, listen to everyone, involve everyone in decision-making, avoid infighting, build trust.

Create a process for resolving conflict. Do so before conflict arises. Set up rules to help the group decide how conflict will be handled.

Use the strengths of each team member. All students bring different strengths. Use the unique value of each person.

Do not do all the work yourself. Work with your team to get the work done. The project output is often less important than the experience.

What Does It Take to Lead a Team?

To borrow from Shakespeare, “Some people are born leaders, some achieve leadership, and some have leadership thrust upon them.” In a successful career, you will probably be asked to lead a team. What will you have to do to succeed as a leader?

Like so many of the questions that we ask in this book, this question does not have any simple answers. We can provide one broad answer: a leader must help members develop the attitudes and behaviour that contribute to team success: interdependence, collective responsibility, shared commitment, and so forth.

Team leaders must be able to influence their team members. Notice that we say influence: except in unusual circumstances, giving commands and controlling everything directly does not work very well.110 As one team of researchers puts it, team leaders are more effective when they work with members rather than on them.111 Hand-in-hand with the ability to influence is the ability to gain and keep the trust of team members. People are not likely to be influenced by a leader whom they perceive as dishonest or selfishly motivated.

Assuming you were asked to lead a team, there are certain leadership skills and behaviours that would help you influence your team members and build trust. Let us glance at some of them:

Show integrity. Do what you say you will do and act under your stated values. Be honest in communicating and follow through on promises.

Be clear and consistent. Let members know you are certain about what you want and remember that being clear and consistent reinforces your credibility.

Generate positive energy. Be optimistic and compliment team members. Recognize their progress and success.

Acknowledge common points of view. Even if you are about to propose change, recognize the value of the views that members already hold in common.

Manage agreement and disagreement. When members agree with you, confirm your shared point of view. When they disagree, acknowledge both sides of the issue and support your own with strong, clearly presented evidence.

Encourage and coach. Buoy up members when they run into new and uncertain situations and when success depends on their performing at a high-level.

Share information. Give members the information they need and let them know you are knowledgeable about team tasks and individual talents. Check with team members regularly to find out what they are doing and how the job is progressing.

A team contract is important to ensure all members have input on how the team will work together. This contract can also be referenced if a team member is not working to their expectations.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: link.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: link.

Key Takeaways

A team (or a work team) is a group of people with complementary skills and diverse areas of expertise who work together to achieve a specific goal.

Work teams have five key characteristics:

- Accountable for achieving specific common goals.

- Function interdependently.

- Stable.

- Have authority.

- Operate in a social context.

Work teams may be of several types:

- In the traditional manager-led team, the leader defines the team’s goals and activities and achieves its assigned goals.

- The leader of a self-managing team may determine overall goals, but employees control the activities needed to meet them.

- A cross-functional team takes advantage of the special expertise of members drawn from different functional areas of the company.

- On virtual teams, geographically dispersed members interact electronically while pursuing a common goal.

Group cohesiveness refers to the attractiveness of a team to its members. If a group is high in cohesiveness, membership is quite satisfying to its members; if it is low in cohesiveness, members are unhappy with it and may even try to leave it.

As the business world depends more and more on teamwork, it is increasingly important for incoming members of the workforce to develop skills and experience in team-based activities.

Every team requires some mixture of three skill sets:

- Technical skills: skills needed to perform specific tasks.

- Decision-making and problem-solving skills: skills needed to identify problems, evaluate alternative solutions, and decide on the best options.

- Interpersonal skills: skills in listening, providing feedback, and resolving conflict.

The Cultural Environment

Even when two people from the same country communicate, there is always a possibility of misunderstanding. When people from different countries get together, that possibility increases substantially. Differences in communication styles reflect differences in culture: the system of shared beliefs, values, customs, and behaviours that govern the interactions of members of a society. Cultural differences create challenges in successful international business dealings. Let us look at a few of these challenges.

Language

English is the international language of business. The natives of such European countries as France and Spain certainly take pride in their own languages and cultures, English is the business language of the European community.

Whereas only a few educated Europeans have studied Italian or Norwegian, most have studied English. Similarly, on the South Asian subcontinent, where hundreds of local languages and dialects are spoken, English is the official language. In most corners of the world, English-only speakers (most Canadians) have no problem finding competent translators and interpreters. So why is language an issue for English speakers doing business in the global marketplace? In many countries, only members of the educated classes speak English. The larger population (usually the market you want to tap) speaks the local tongue. Advertising messages and sales appeals must take this into account. Multiple English translations of an advertising slogan can cause a humorous (and perhaps serious) blunder.

Lost in Translation

In Belgium, the translation of the slogan of an American auto-body company, Body by Fisher, came out as Corpse by Fisher.

Translated into German, the slogan, Come Alive with Pepsi became Come Out of the Grave with Pepsi.

A U.S. computer company in Indonesia translated “software” as “underwear”.

A German chocolate product called “Zit” did not sell well in the U.S.

An English-speaking car wash company in Francophone Quebec advertised itself as a “lavement d’auto” or “car enema” instead of the correct “lavage d’auto.

In the 1970s, General Motors’ Chevy Nova did not get on the road in Puerto Rico, in part because “nova” in Spanish means “it doesn’t go”.

SOURCE: Ketut Subiyanto.

Relying on translators and interpreters puts you as an international businessperson at a disadvantage. You are privy only to interpretations of the messages that you are getting, and this handicap can cause a real competitive problem. Maybe you will misread the subtler intentions of the person with whom you are trying to conduct business. The best way to combat this problem is to study foreign languages. Most people appreciate some effort to communicate in their local language, even on the most basic level. They even appreciate mistakes you make resulting from a desire to show your genuine interest in the language of your counterparts in foreign countries. The same principle goes double when you are introducing yourself to non- English speakers in Canada. Few things work faster to encourage a friendly atmosphere than a native speaker’s willingness to greet a foreign guest in the guest’s native language.

Time and Sociability

North American people take many of the cultural aspects of our business practices for granted. Our meetings for instance, focus on business issues, and we tend to start and end our meetings on schedule. These habits stem from a broader cultural preference: we dislike wasting time (It was an American, Benjamin Franklin, who coined the phrase “Time is money”). This preference, however, is not universal. The expectation that meetings will start on time and adhere to precise agendas is common in parts of Europe (especially the Germanic countries), as well as in Canada, but elsewhere (i.e. Latin America and the Middle East) people are often late to meetings.

High- and Low-Context Cultures

Likewise, do not expect businesspeople from these regions (or businesspeople from most of Mediterranean Europe) to “get down to business” as soon as a meeting has started. They will probably ask about your health and that of your family, inquire whether you are enjoying your visit to their country, suggest local foods, and generally appear to be avoiding serious discussion at all costs. For Canadians, such topics are conducive to nothing but idle chitchat, but in certain cultures, getting started this way is a matter of simple politeness and hospitality.

Intercultural Communication

Different cultures have different communication styles, a fact that can take some getting used to. For example, degrees of animation in expression can vary from culture to culture. Southern Europeans and Middle Easterners are quite animated, favouring expressive body language along with hand gestures and raised voices. Northern Europeans are far more reserved. The English, for example, are famous for their understated style and the Germans for their formality in most business settings. In addition, the distance at which one feels comfortable when talking with someone varies by culture. People from the Middle East like to converse from a foot or fewer, while North American people prefer more personal space.

Finally, while people in some cultures prefer to deliver direct, simple messages, others use language that is subtler or more indirect. North Americans and most Northern Europeans fall into the former category, and many Asians into the latter. But even within these categories, there are differences. Though typically polite, Chinese and Koreans are extremely direct in expression, while Japanese are indirect: They use vague language and avoid saying “no” even if they do not intend to do what you ask. They worry that turning someone down will cause their “losing face” (i.e. embarrassment or loss of credibility) and so they avoid doing this in public.

In summary, learn about a country’s culture and use your knowledge to help improve the quality of your business dealings. Learn to value the subtle differences among cultures, but do not allow cultural stereotypes to dictate how you interact with people from any culture. Treat each person as an individual and get to know what he or she is about.

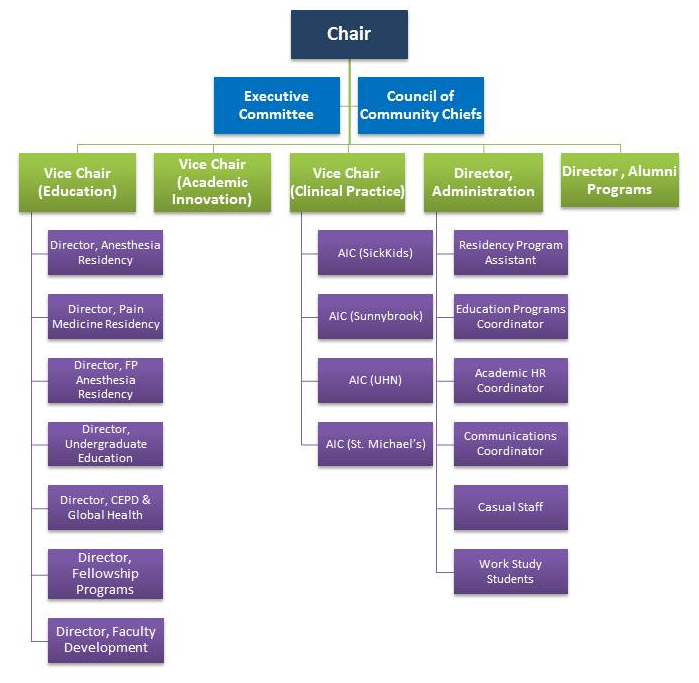

The Organization Chart

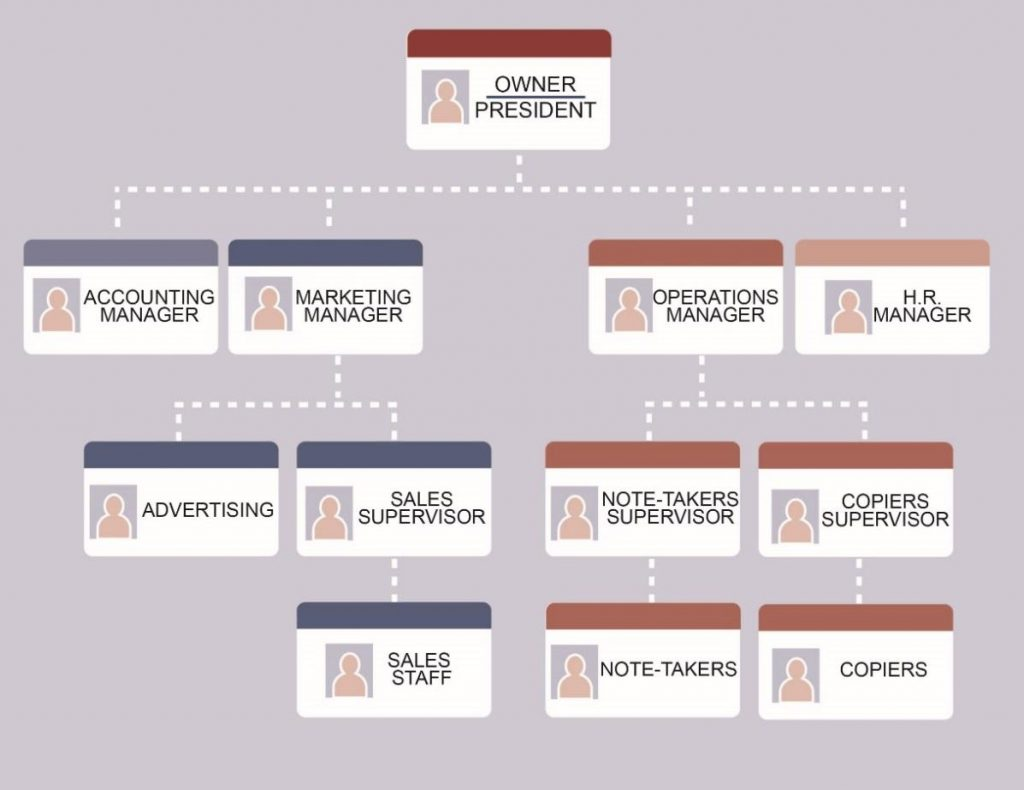

Once an organization has set its structure, it can represent that structure in an organization chart: a diagram delineating the interrelationships of positions within the organization. Here is an example of this type of organization chart:

Figure 3. Potential organization chart for the Note-4-You company

Figure 4. Advanced Organizational Structure

Imagine putting yourself at the top of the chart, as the company’s president. You would then fill in the level directly below your name with the names and positions of the people who work directly for you like your accounting, marketing, operations, and human resources managers. The next level identifies the people who work for these managers. Because you have started out small, neither your accounting manager nor your human resources manager will be currently managing anyone directly. Your marketing manager, however, will oversee one person in advertising and a sales supervisor (who oversees the sales staff). Your operations manager will oversee two individuals, one to supervise note-takers and one to supervise the people responsible for making copies. The lines between the positions on the chart show the reporting relationships; for example, the Note-Takers Supervisor reports directly to the Operations Manager.

Although the structure suggests that you will communicate only with your four direct reports, this is not the way things normally work in practice. Behind every formal communication network there lies a network of informal communications, unofficial relationships among members of an organization. You might find that over time, you receive communications directly from members of the sales staff; in fact, you might encourage this line of communication.

Now let us look at the chart of an organization that relies on a divisional structure. Educational institutions are a good example, either as a whole or even at the departmental level. Use the one below as an example or look at your own institution’s organization chart. Many companies with a divisional structure organize by product, services, or customer base. Educational institutions reflect a mix of those divisional structure options.

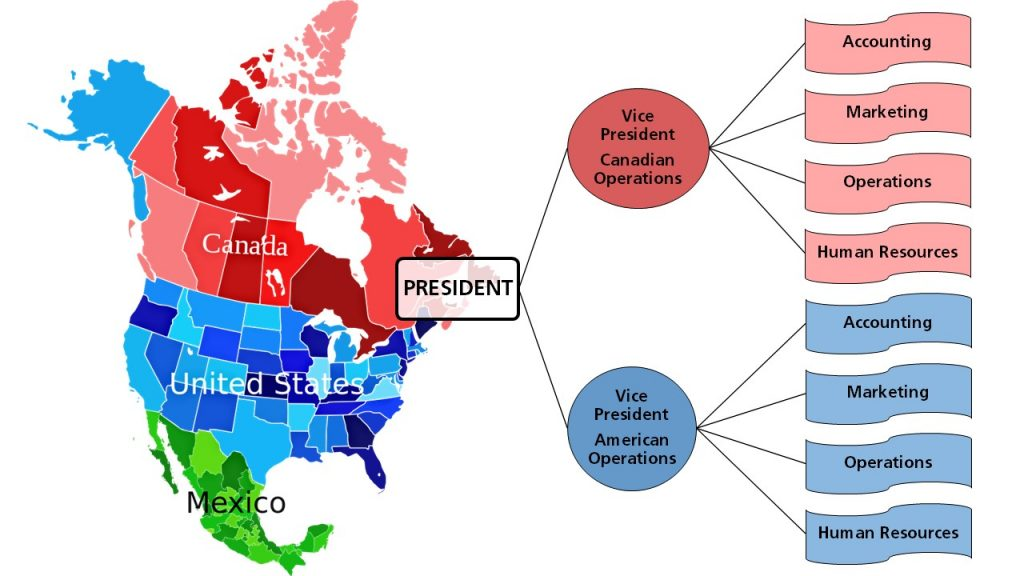

Figure 5. Global Organizational Chart

Over time, companies revise their organizational structures to accommodate growth and changes in the external environment. It is not uncommon, for example, for a firm to adopt a functional structure in its early years. Then, as it becomes bigger and more complex, it might move to a divisional structure, perhaps to accommodate new products or to become more responsive to certain customers or geographical areas. Some companies might ultimately rely on a combination of functional and divisional structures. This could be a friendly approach for a credit card company that issues cards in both the United States and Canada. An outline of this firm’s organization chart might look like the following diagram.

Chain of Command

The vertical connecting lines in the organization chart show the firm’s chain of command: the authority relationships among people working at different levels of the organization. They show who reports to whom. When you are examining an organization chart, you will probably want to know whether each person reports to one or more supervisors: to what extent is there unity of command? To understand why unity of command is an important organizational feature, think about it from a personal standpoint. Would you want to report to multiple bosses? What happens if you get conflicting directions? Whose directions would you follow?

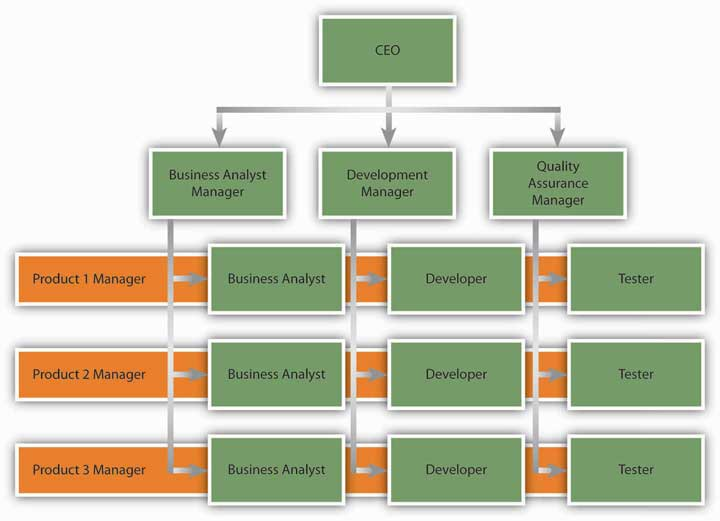

There are, however, conditions under which an organization and its employees can benefit by violating the unity of command principle. Under a matrix structure, for example, employees from various functional areas (product design, manufacturing, finance, marketing, human resources, etc.) form teams to combine their skills in working on a specific project or product. This matrix organization chart might look like the one in the following figure.

Nike sometimes uses this type of arrangement. To design new products, the company may create product teams made up of designers, marketers, and other specialists with expertise in sports categories, like running shoes or basketball shoes. Both the team manager and the head of his or her functional department would evaluate each team member.

Figure 6. Organizational Matrix

Span of Control

Another thing to notice about a firm’s chain of command is the number of layers between the top managerial position and the lowest managerial level. New organizations have only a few layers of management, an organizational structure that is often called flat. Let us say, for instance, that a member of the Notes-4-You sales staff wanted to complain about slow sales among a certain group of students. That person’s message would have to filter upward through only two management layers (the sales supervisor and the marketing manager) before reaching the president.

As a company grows, it adds more layers between the top and the bottom. Added layers of management can slow down communication and decision-making, causing the organization to become less efficient and productive. That is one reason many of today’s organizations are restructuring to become flatter.

There are trade-offs between the advantages and disadvantages of flat and tall organizations. Companies determine which trade-offs to make according to a principle called span of control, which measures the number of people reporting to a particular manager. If, for example, you remove layers of management to make your organization flatter, you end up increasing the number of people reporting to a particular supervisor. If you refer to the organization chart for Notes-4-You, you’ll recall that, under your present structure, four managers report to you as the president: the heads of accounting, marketing, operations, and human resources. Two of these managers have positions reporting to them: the advertising manager and sales supervisor report to the marketing manager, while the note-takers supervisor and the copiers supervisor report to the operations manager. Let us say that you remove a layer of management by getting rid of the marketing and operations managers. Your organization would be flattered, but what would happen to your workload? As president, you would now have six direct reports rather than four: accounting manager, advertising manager, sales manager, note-taker supervisor, copier supervisor, and human resources manager.

What is better? A narrow span of control (with few direct reports) or a wide span of control (with many direct reports)? The answer to this question depends on several factors, including frequency and type of interaction, proximity of subordinates, competence of both supervisor and subordinates, and the nature of the work being supervised. For example, you would expect a much wider span of control at a non-profit call centre than in a hospital emergency room.

Delegating Authority

Given the tendency toward flatter organizations and wider spans of control, how do managers handle increased workloads? They must learn how to handle delegation, entrusting work to subordinates. Unfortunately, many managers are reluctant to delegate. As a result, they not only overburden themselves with tasks that others could handle, but they also deny subordinates the opportunity to learn and develop new skills.

Responsibility and Authority

As owner of Notes-4-You, you will probably want to control every aspect of your business, especially during the startup stage. But as the organization grows, assign responsibility for performing certain tasks to other people. You will also have to accept the fact that responsibility alone (the duty to perform a task) will not be enough to get the job done. You will need to grant subordinates the authority they require completing a task, such as the power to decide (they will also need sufficient resources). Ultimately, you will hold your subordinates accountable for their performance.

Centralization and Decentralization

If/when your company expands (i.e. offering note-taking services at other schools), decide whether most individuals should still make decisions at the top or delegated to lower-level employees. The first option, in which most decision-making is concentrated at the top – centralization. The second option, which spreads decision-making throughout the organization, is decentralization.

Centralization has the advantage of consistency in decision-making. The same top managers make key decisions in a centralized model, which tend to be more uniform than if decisions were made by a variety of different people at lower levels in the organization. In most cases, decisions can also be made more quickly provided that top management does not control too many decisions. There are disadvantages to centralization, including if top management makes virtually all key decisions, then lower-level managers will feel under-used and will not develop decision-making skills that would help them become promotable. An overly centralized model cannot consider information that only front-line employees have or might delay the decision-making process. Consider a case where the sales manager for an account is meeting with a customer representative who makes a request for a special sale price; the customer offers to buy 50% more product if the sales manager will reduce the price by 5% for one month. If the sales manager had to get approval from the head office, the opportunity might disappear before she could get approval, a competitor’s sales manager might be the customer’s next meeting.

An overly decentralized decision model has its risks as well. Imagine a case in which a company had adopted a geographically based divisional structure and had decentralized decision-making. To expand its business, suppose one division expanded its territory into the geography of another division. If headquarters approval for such a move was not required, the divisions of the company might end up competing against each other, to the detriment of the organization. Companies that wish to maximize their potential must find the right balance between centralized and decentralized decision-making.

Key Takeaways

Managers coordinate the activities identified in the planning process among individuals, departments, or other units and allocate the resources needed to perform them.

Typically, there are three levels of management: top managers, who handle overall performance; middle managers, who report to top managers and oversee lower-level managers; and first-line managers, who supervise employees to ensure work is performed correctly and on time.

Management must develop an organizational structure, or arrangement of people within the organization, that will best achieve company goals.

The process begins with specialization by dividing necessary tasks into jobs; the principle of grouping jobs into units is called departmentalization.

Units are then grouped into an appropriate organizational structure. Functional organization groups people with comparable skills and tasks; divisional organization creates a structure composed of self-contained units based on product, customer, process, or geographical division. Forms of organizational division are often combined.

An organization’s structure is represented in an organization chart, a diagram showing the interrelationships of its positions.

- This chart highlights the chain of command, or authority relationships among people working at different levels.

- It also shows the number of layers between the top and lowest managerial levels. An organization with few layers has a wide span of control, with each manager overseeing many subordinates; with a narrow span of control, only a few subordinates reports to each manager.

Feedback/Errata