Human Resources

13 Chapter 13: People and Organization

People and Organization

“Students can’t afford to pay $200 for a textbook. The old business model wasn’t adapting fast enough to the Internet, where so much information was available for free or low-cost,” says Jeff, referring to traditional publishers. “We knew there had to be a better way to publish high-quality material and eliminate price and access barriers.”

Since its beginning in 2007, more than thirty employees have joined this fast-growing start-up, located just north of New York City, in Irvington, New York. The company has become a recognized pioneer in transforming higher educational publishing and textbook affordability.

FWK is upending the $8 billion college textbook industry with a new business model that focuses on affordability and personalization. Professors who assign FWK books are free to revise and edit the material to match their course and help improve student success. Students have a choice of affordable print and digital formats that they can access online or on a laptop, tablet, e-reader or smartphone for a fraction of the price that most traditional publishers charge.

Rather than hamper the company’s growth, the economic downturn has actually highlighted the value of its products and the viability of its business model. Despite the bad economy, FWK has been able to raise over $30 million in venture capital. Clearly, they are doing something right.

The numbers tell the story. Since the launch of their first ten books in spring 2009 (there are more than one hundred fifteen books to date), faculty at more than two thousand institutions in forty-four countries have adopted FWK books. As a result, more than 600,000 students have benefited from affordable textbook choices that lower costs, increase access and personalize learning.

In 2010, 2011 and 2012, EContent magazine named FWK as one of the top one hundred companies that matter most in the digital content industry. FWK was also named 2010 Best Discount Textbook Provider by the Education Resources People’s Choice Awards.

What is particularly refreshing is Jeff’s philosophy about people and work. “Give talented people an opportunity to build something meaningful, the tools to do it, and the freedom to do one’s best.” He believes in flexibility with people and their jobs, and, to that end, employees have the option to work remotely. There is no question that FWK is an innovator in the educational publishing industry, but it also knows how to treat people well and provide a challenging environment that fosters personal growth.[1] [2] [3]

Principles of Management and Organization

Learning Objectives

- Understand the functions of management.

- Explain the three basic leadership styles.

- Explain the three basic levels of management.

- Understand the management skills that are important for a successful small business.

- Understand the steps in ethical decision making.

What Is Management?

There is no universally accepted definition for management. The definitions run the gamut from very simple to very complex. For our purposes, we define management as “the application of planning, organizing, staffing, directing, and controlling functions in the most efficient manner possible to accomplish meaningful organizational objectives.”[4] Put more simply, management is all about achieving organizational objectives through people and other resources.[5]

Management principles apply to all organizations—large or small, for-profit or not-for-profit. Even one-person small businesses need to be concerned about management principles because without a fundamental understanding of how businesses are managed, there can be no realistic expectation of success. Remember that the most common reason attributed to small business failure is failure on the part of management.

Management Functions

On any given day, small business owners and managers will engage in a mix of many different kinds of activities—for example, deal with crises as they arise, read, think, write, talk to people, arrange for things to be done, have meetings, send e-mails, conduct performance evaluations, and plan. Although the amount of time that is spent on each activity will vary, all the activities can be assigned to one or more of the five management functions: planning, organizing, staffing, directing, and controlling (Figure 13.1 “Management Functions”).

Planning

Planning “is the process of anticipating future events and conditions and determining courses of action for achieving organizational objectives.”[6] It is the one step in running a small business that is most commonly skipped, but it is the one thing that can keep a business on track and keep it there.[7] Planning helps a business realize its vision, get things done, show when things cannot get done and why they may not have been done right, avoid costly mistakes, and determine the resources that will be needed to get things done.[8] [9]

Organizing

Organizing consists of grouping people and assigning activities so that job tasks and the mission can be properly carried out.[10] Establishing a management hierarchy is the foundation for carrying out the organizing function.

Contrary to what some people may believe, the principle of organizing is not dead. Rather, it is clearly important “to both the organization and its workers because both the effectiveness of organizations and worker satisfaction require that there be clear and decisive direction from leadership; clarity of responsibilities, authorities, and accountabilities; authority that is commensurate with responsibility and accountability; unified command (each employee has one boss); a clear approval process; and, rules governing acceptable employee behavior.”[11] Except for a small business run solely by its owner, every small business needs a management hierarchy—no matter how small. Each person in the business should know who is responsible for what, have the authority to carry out his or her responsibilities, and not get conflicting instructions from different bosses. The absence of these things can have debilitating consequences for the employees in particular and the business in general.[12]

Video Link 13.1 Glassblowing Business Thrives

Lesson learned: Everyone should know his or her role in the business.

www.cnn.com/video/#/video/living/2010/10/15/mxp.sbs.glass.business.hln?iref=videosearch

Staffing

The staffing function involves selecting, placing, training, developing, compensating, and evaluating (the performance appraisal) employees.[13] Small businesses need to be staffed with competent people who can do the work that is necessary to make the business a success. It would also be extremely helpful if these people could be retained. Many of the issues associated with staffing in a small business are discussed in Section 13.4 “People”.

Directing

Directing is the managerial function that initiates action: issuing directives, assignments, and instructions; building an effective group of subordinates who are motivated to do what must be done; explaining procedures; issuing orders; and making sure that mistakes are corrected.[14][15] Directing is part of the job for every small business owner or manager. Leading “is the process of influencing people to work toward a common goal [and] motivating is the process of providing reasons for people to work in the best interests of an organization.” [16]

Different situations call for different leadership styles. In a very influential research study, Kurt Lewin established three major leadership styles: autocratic, democratic, and laissez-faire.[17] Although good leaders will use all three styles depending on the situation, with one style normally dominant, bad leaders tend to stick with only one style.[18]

Autocratic leadership occurs when a leader makes decisions without involving others; the leader tells the employees what is to be done and how it should be accomplished.[19][20] Lewin et al. found that this style creates the most discontent.[21] However, this style works when all the information needed for a decision is present, there is little time to make a decision, the decision would not change as a result of the participation of others, the employees are well motivated, and the motivation of the people who will carry out subsequent actions would not be affected by whether they are involved in the decision or not.[22][23] This leadership style should not be used very often.

Democratic leadership involves other people in the decision making—for example, subordinates, peers, superiors, and other stakeholders—but the leader makes the final decision. Rather than being a sign of weakness, this participative form of leadership is a sign of strength because it demonstrates respect for the opinions of others. The extent of participation will vary depending on the leader’s strengths, preferences, beliefs, and the decision to be made, but it can be as extreme as fully delegating a decision to the team.[24] This leadership style works well when the leader has only part of the information and the employees have the other part. The participation is a win-win situation, where the benefits are mutual. Others usually appreciate this leadership style, but it can be problematic if there is a wide range of opinions and no clear path for making an equitable, final decision.[25][26] In experiments that Lewin et al. conducted with others, the democratic leadership style was revealed as the most effective.[27]

Laissez-faire leadership (or delegative or free-reign leadership) minimizes the leader’s involvement in decision making. Employees are allowed to make decisions, but the leader still has responsibility for the decisions that are made. The leader’s role is that of a contact person who provides helpful guidance to accomplish objectives.[28] This style works best when employees are self-motivated and competent in making their own decisions, and there is no need for central coordination; it presumes full trust and confidence in the people below the leader in the hierarchy.[29][30] However, this is not the style to use if the leader wants to blame others when things go wrong.[31] This style can be problematic because people may tend not to be coherent in their work and not inclined to put in the energy they did when having more visible and active leadership.[32][33]

Good leadership is necessary for all small businesses. Employees need someone to look up to, inspire and motivate them to do their best, and perhaps emulate. In the final analysis, leadership is necessary for success. Without leadership, “the ship that is your small business will aimlessly circle and eventually run out of power or run aground.”[34]

Don’t Be This Kind of Leader or Manager

Here are some examples of common leadership styles that should be avoided.

- Post-hoc management. As judge and jury, management is always right and never to blame. This approach ensures security in the leader’s job. This style is very common in small companies where there are few formal systems and a general autocratic leadership style.[35]

- Micromanagement. Alive and well in businesses of all sizes, this style assumes that the subordinate is incapable of doing the job, so close instruction is provided, and everything is checked. Subordinates are often criticized and seldom praised; nothing is ever good enough. It is really the opposite of leadership.[36]

- Seagull management. This humorous term is used to describe a management style whereby a person flies in, poops on you, and then flies away.[37] When present, such people like to give criticism and direction in equal quantities—with no real understanding of what the job entails. Before anyone can object or ask what the manager really wants, he or she is off to an important meeting. Everyone is actively discouraged from saying anything, and eye contact is avoided.[38]

- Mushroom management. This manager plants you knee-deep (or worse) in the smelly stuff and keeps you in the dark.[39] Mushroom managers tend to be more concerned about their own careers and images. Anyone who is seen as a threat may be deliberately held back. These managers have their favorites on whom they lavish attention and give the best jobs. Everyone else is swept away and given the unpopular work. Oftentimes, mushroom managers are incompetent and do not know any better. We have all seen at least one manager of this type.

- Kipper management. This is the manager who is, like a fish, two-faced because employees can see only one face at a time. To senior managers, this person is typically a model employee who puts business first and himself last. To subordinates, however, the reverse is often the case. The subordinates will work hard to get things done in time, but they are blamed when things go wrong—even if it is not their fault. The kipper will be a friend when things need to get done and then stab the subordinates in the back when glory or reward is to be gained.[40] We have all seen this kind of manager, perhaps even worked for one.

Controlling

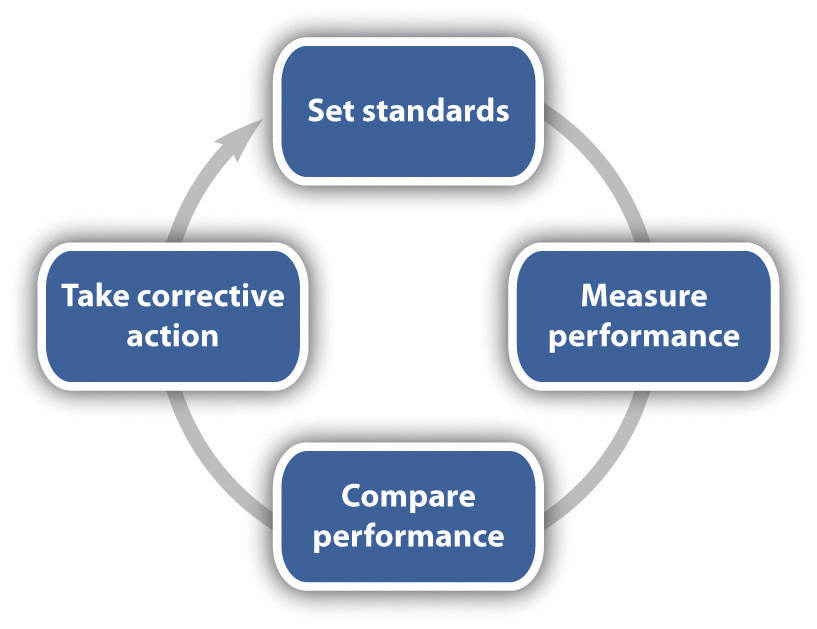

Controlling is about keeping an eye on things. It is “the process of evaluating and regulating ongoing activities to ensure that goals are achieved.”[41] Controlling provides feedback for future planning activities and aims to modify behavior and performance when deviations from plans are discovered.[42] There are four commonly identified steps in the controlling process[43][44]. (See Figure 13.2 “The Controlling Function”.) Setting performance standards is the first step. Standards let employees know what to expect in terms of time, quality, quantity, and so forth. The second step is measuring performance, where the actual performance or results are determined. Comparing performance is step three. This is when the actual performance is compared to the standard. The fourth and last step, taking corrective action, involves making whatever actions are necessary to get things back on track. The controlling functions should be circular in motion, so all the steps will be repeated periodically until the goal is achieved.

Levels of Management

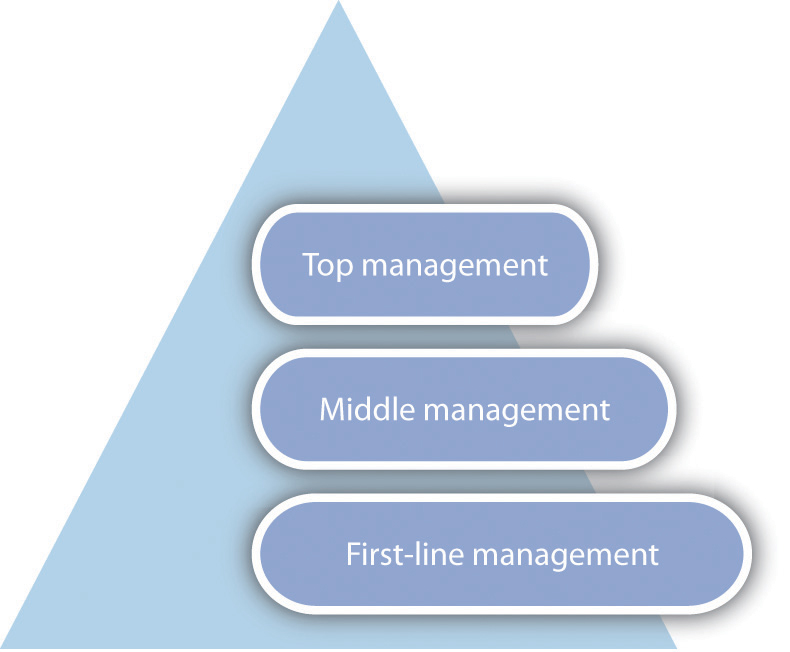

As a small business grows, it should be concerned about the levels or the layers of management. Also referred to as the management hierarchy, (Figure 13.3 “The Management Hierarchy”) there are typically three levels of management: top or executive, middle, and first-line or supervisory. To meet a company’s goals, there should be coordination of all three levels.

Top management also referred to as the executive level, guides and controls the overall fortunes of a business.[45] This level includes such positions as the president or CEO, the chief financial officer, the chief marketing officer, and executive vice presidents. Top managers devote most of their time to developing the mission, long-range plans, and strategy of a business—thus setting its direction. They are often asked to represent the business in events at educational institutions, community activities, dealings with the government, and seminars and sometimes as a spokesperson for the business in advertisements. It has been estimated that top managers spend 55 percent of their time planning.[46]

Middle management is probably the largest group of managers. This level includes such positions as regional manager, plant manager, division head, branch manager, marketing manager, and project director. Middle managers, a conduit between top management and first-line management, focus on specific operations, products, or customer groups within a business. They have responsibility for developing detailed plans and procedures to implement a firm’s strategic plans.[47]

First-line or supervisory management is the group that works directly with the people who produce and sell the goods and/or the services of a business; they implement the plans of middle management.[48] They coordinate and supervise the activities of operating employees, spending most of their time working with and motivating their employees, answering questions, and solving day-to-day problems.[49] Examples of first-line positions include supervisor, section chief, office manager, foreman, and team leader.[50][51]

In many small businesses, people often wear multiple hats. This happens with management as well. One person may wear hats at each management level, and this can be confusing for both the person wearing the different hats and other employees. It is common for the small business owner to do mostly first-level management work, with middle or top management performed only in response to a problem or a crisis, and top-level strategic work rarely performed.[52] This is not a good situation. If the small business is large enough to have three levels of management, it is important that there be clear distinctions among them—and among the people who are in those positions. The small business owner should be top management only. This will eliminate confusion about responsibility and accountability.

Management Skills

Management skill “is the ability to carry out the process of reaching organizational goals by working with and through people and other organizational resources.”[53] Possessing management skill is generally considered a requirement for success.[54] An effective manager is the manager who is able to master four basic types of skills: technical, conceptual, interpersonal, and decision making.

Technical skills “are the manager’s ability to understand and use the techniques, knowledge, and tools and equipment of a specific discipline or department.”[55] These skills are mostly related to working with processes or physical objects. Engineering, accounting, and computer programming are examples of technical skills.[56] Technical skills are particularly important for first-line managers and are much less important at the top management level. The need for technical skills by the small business owner will depend on the nature and the size of the business.

Conceptual skills “determine a manager’s ability to see the organization as a unified whole and to understand how each part of the overall organization interacts with other parts.”[57] These skills are of greatest importance to top management because it is this level that must develop long-range plans for the future direction of a business. Conceptual skills are not of much relevance to the first-line manager but are of great importance to the middle manager. All small business owners need such skills.

Interpersonal skills, “include the ability to communicate with, motivate, and lead employees to complete assigned activities,”[58] hopefully building cooperation within the manager’s team. Managers without these skills will have a tough time succeeding. Interpersonal skills are of greatest importance to middle managers and are somewhat less important for first-line managers. They are of least importance to top management, but they are still very important. They are critical for all small business owners.

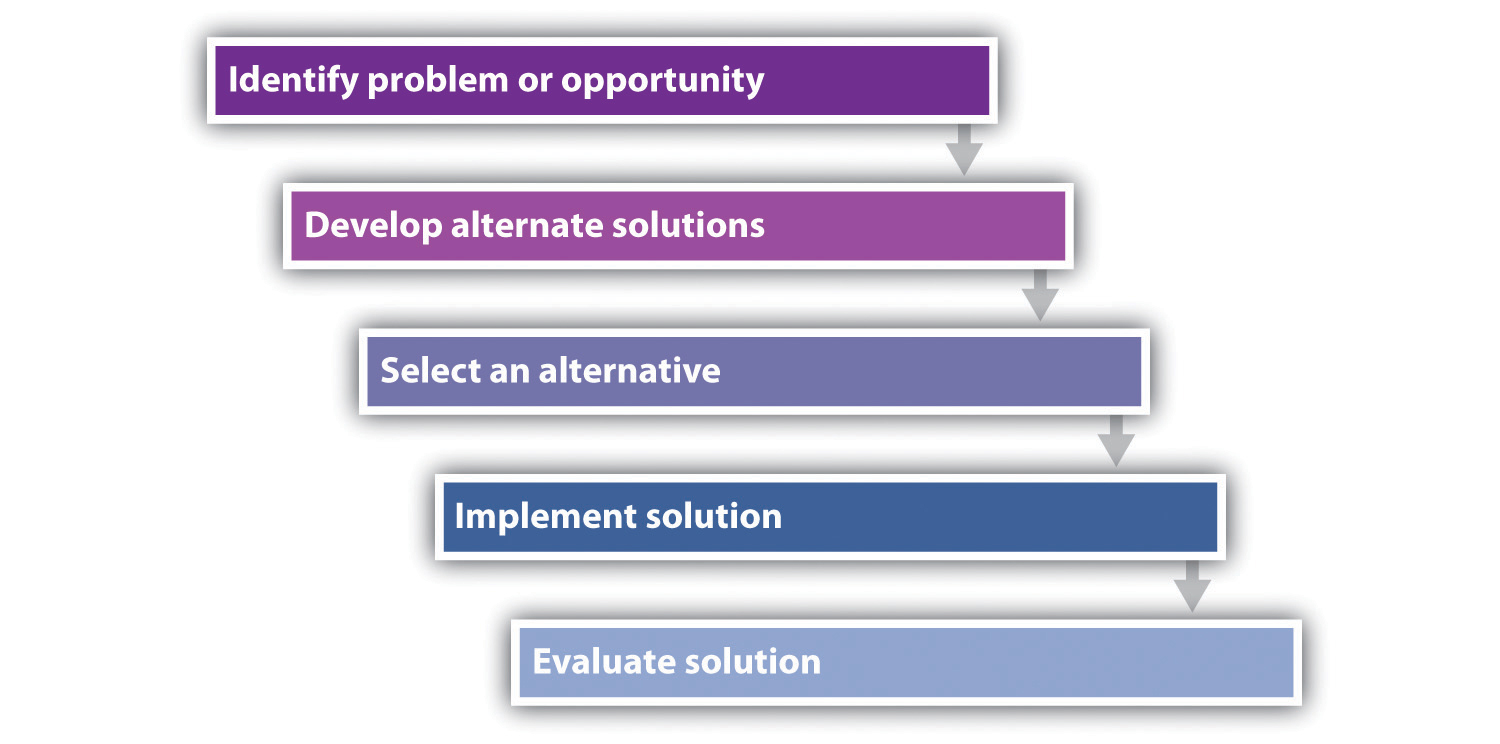

The fourth basic management skill is decision making (Figure 13.4 “Management Decision Making”), the ability to identify a problem or an opportunity, creatively develop alternative solutions, select an alternative, delegate authority to implement a solution, and evaluate the solution.[59]

Figure 13.4 Management Decision Making

Making good decisions is never easy, but doing so is clearly related to small business success. “Decisions that are based on a foundation of knowledge and sound reasoning can lead the company into long-term prosperity; conversely, decisions that are made on the basis of flawed logic, emotionalism, or incomplete information can quickly put a small business out of commission.”[60]

A Framework for Ethical Decision Making

Small business decisions should be ethical decisions. Making ethical decisions requires that the decision maker(s) be sensitive to ethical issues. In addition, it is helpful to have a method for making ethical decisions that, when practiced regularly, becomes so familiar that it is automatic. The Markkula Center for Applied Ethics recommends the following framework for exploring ethical dilemmas and identifying ethical courses of action.[61] However, in many if not most instances, a small business owner or manager and an employee will usually know instinctively whether a particular decision is unethical.

Recognize an Ethical Issue

-

Could this decision or situation be damaging to someone or some group? Does this decision involve a choice between a good and a bad alternative or perhaps between two “goods” or between two “bads”?

-

Is this issue about more than what is legal or most efficient? If so, how?

Get the Facts

-

What are the relevant facts of the case? What facts are not known? Can I learn more about the situation? Do I know enough to make a decision?

-

What individuals and groups have an important stake in the outcome? Are some concerns more important? Why?

-

What are the options for acting? Have all the relevant persons and groups been consulted? Have I identified creative options?

Evaluate Alternative Actions

- Which option will produce the most good and do the least harm?

- Which option best respects the rights of all who have a stake?

- Which option treats people equally or proportionately?

- Which option best serves the community as a whole, not just some members?

- Which option leads me to act as the sort of person I want to be?

Make a Decision and Test It

- Considering all these approaches, which option best addresses the situation?

- If I told someone I respect—or told a television audience—which option I have chosen, what would they say?

Act and Reflect on the Outcome

- How can my decision be implemented with the greatest care and attention to the concerns of all stakeholders?

- How did my decision turn out, and what have I learned from this specific situation?

Key Takeaways

- Management principles are important to all small businesses.

- Management decisions will impact the success of a business, the health of its work environment, its growth if growth is an objective, and customer value and satisfaction.

- Management is about achieving organizational objectives through people.

- The most common reason attributed to small business failure is failure on the part of management.

- On any given day, a typical small business owner or manager will be engaged in some mix of planning, organizing, staffing, directing, and controlling.

- Different situations call for different leadership styles. The three major styles are autocratic, democratic, and laissez-faire. Bad leaders typically stick with one style.

- The management hierarchy is typically composed of three levels: top or executive, middle, and first-line or supervisory. If a small business is large enough to have these three levels, it is important that there be a clear distinction between them.

- Management skills are required for success. Technical, conceptual, interpersonal, and decision-making skills will be of differing importance depending on the management level.

Exercises

- Apply the four steps in the controlling function for Frank’s BarBeQue. Identify and discuss examples of performance standards that Frank might use. Indicate which standards should be numerically based. How could he measure performance? What corrective action should he take if performance does not meet the established performance standards?

Organizational Design

Learning Objectives

- Understand why an organizational structure is necessary.

- Understand organizational principles.

- Explain the guidelines for organizing a small business.

- Describe the different forms of organizational structure and how they apply to small businesses.

Organizing consists of grouping people and assigning activities so that job tasks and the mission of a business can be properly carried out. The result of the organizing process should be an overall structure that permits interactions among individuals and departments needed to achieve the goals and objectives of a business.[62] Although small business owners may believe that they do not need to adhere to the organizing principles of management, nothing could be farther from the truth.

Principles represent guidelines that managers can use in making decisions. They are not laws etched in stone. At times, principles can be used exactly as the way they are stated; at other times they should be modified or even completely ignored. Small business owners must learn through experience when and where to use [the] principles or to modify them [emphasis added]. Principles when used effectively and in the right context often bring organizational efficiencies and thus result in the growth of the business. Some organizing principles…would apply to small businesses as well as they would to large enterprises and would lead to similar benefits.[63]

There is no single best way to organize. Rather, the organization decision is based on a multitude of factors, including business size, market, product mix, competition, the number of employees, history, objectives and goals, and available financial resources.[64] Each small business must decide what organizational design best fits the business.

Fundamentals of Organization

Ivancevich and Duening maintain that there are several fundamental issues that managers need to consider when making any kind of organizational decision: clear objectives, coordination, formal and informal organization, the organization chart, formal authority, and centralization versus decentralization. Understanding these fundamentals can facilitate the creation of an organizational structure that is a good fit for a small business. [65]

Clear Objectives

Objectives “give meaning to the business—and to the work done by employees—by determining what it is attempting to accomplish.”[66] Objectives provide direction for organizing a firm, helping to identify the work that must be done to accomplish the objectives. This work, in turn, serves as the basis on which to make staffing decisions.

Coordination

The resources of a small business and its employees must be coordinated to minimize duplication and maximize effectiveness.[67] Coordination requires informal communication with and among employees every day. All businesses must continually coordinate the activities of others—an effort that should never be underestimated. Business leaders must make sure that employees have the answers to six fundamental questions:[68]

- What is my job?

- How am I doing?

- Does anyone care?

- How are we doing?

- What are our vision, mission, and values?

- How can I help?

Formal and Informal Organization

When a one-person small business adds employees, some kind of hierarchy will be needed to indicate who does what. This hierarchy often becomes the formal organization —that is, the details of the roles and responsibilities of all employees.[69] Formal organization tends to be static, but it does indicate who is in charge of what. This helps to prevent chaos. The formal organizational structure helps employees feel safe and secure because they know exactly what their chain of command is. The downside of a formal organizational structure is that it typically results in a slower decision-making process because of the numerous groups and people who have to be involved and consulted.[70]

The informal organization is almost never explicitly stated. It consists of all the connections and relationships that relate to how people throughout the organization actually network to get a job done. The informal organization fills the gaps that are created by the formal organization.[71] Although the informal organization is not written down anywhere, it has a tremendous impact on the success of a small business because it is “composed of natural leaders who get things done primarily through the power granted to them by their peers.”[72] Informal groups and the infamous grapevine are firmly embedded in the informal organization. The grapevine (or water cooler) “is the informal communications network within an organization,…completely separate from—and sometimes much faster than—the organization’s formal channels of communication.”[73] Small business owners must acknowledge the existence of the grapevine and figure out how to use it constructively.

Video Clip 13.1 Leading Outside the Lines

The formal and informal organizations need to work together to sustain peak performance over time.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7DNRWgYT-Go

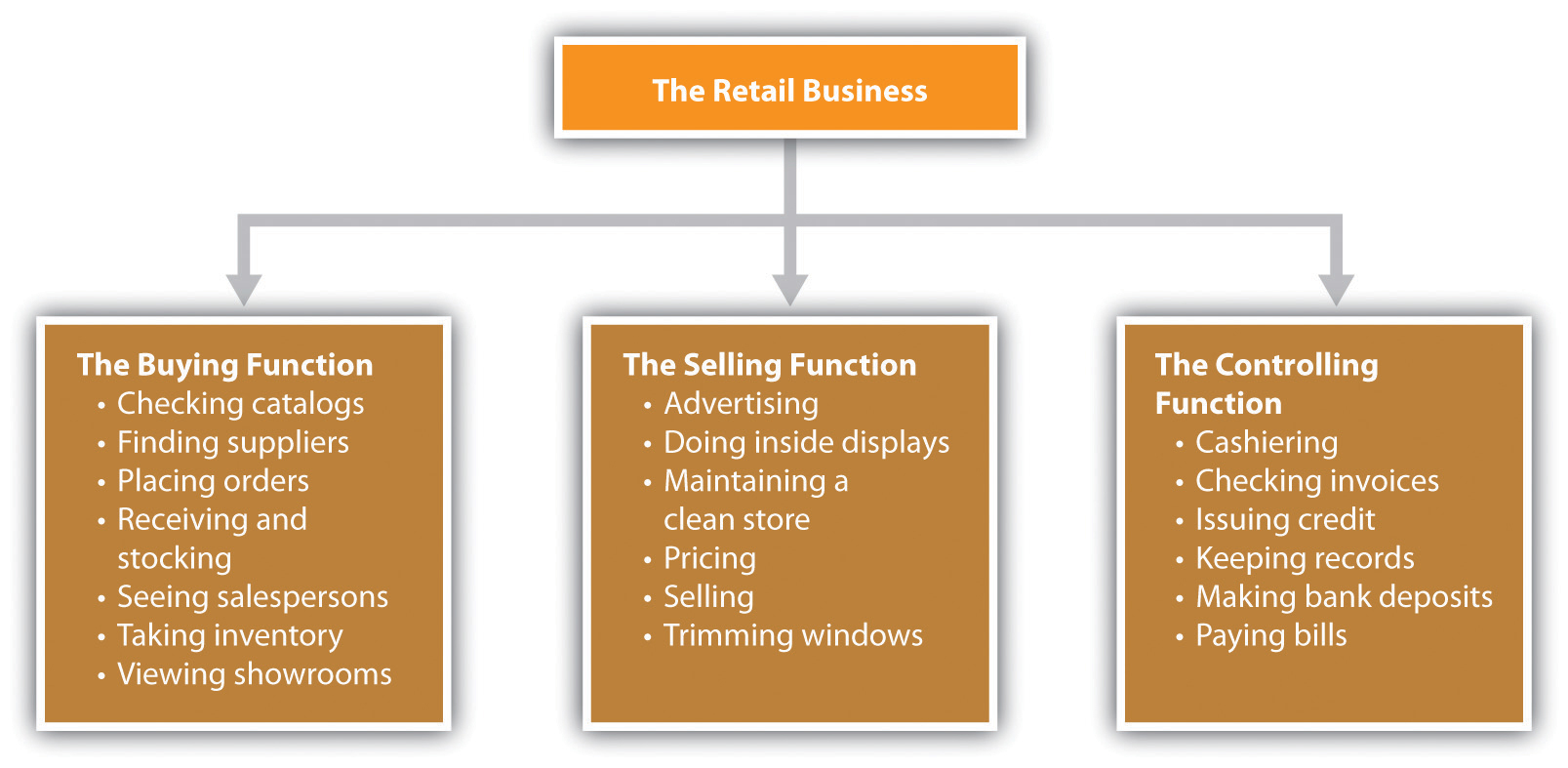

Organization Chart

The organization chart is a visual representation of the formal organization of a business. The chart shows the structure of the organization and the relationships and relative ranks of its positions; it helps organize the workplace while outlining the direction of management control for subordinates.[74] Even the one-person small business can use some kind of organization chart to see what functions need to be performed; this will help ensure that everything that should be done is getting done.[75] Figure 13.5 “Organization Chart for a One-Person Small Business” illustrates a simple organization chart for a one-person retail business.[76]

Figure 13.5 Organization Chart for a One-Person Small Business

Organization charts offer the following benefits:[77] [78]

- Effectively communicate organizational, employee, and enterprise information

- Allow managers to make decisions about resources, provide a framework for managing change, and communicate operational information across the organization

- Are transparent and predictable about what should happen in a business

- Provide a quick snapshot about the formal hierarchy in a business

- Tell everyone in the organization who is in charge of what and who reports to whom

There are, of course, several limitations to organization charts:[79]

- They are static and inflexible, often being out of date as organizations change and go through growth phases.

- They do not aid in understanding what actually happens within the informal organization. The reality is that organizations are often quite chaotic.

- They cannot cope with changing boundaries of firms due to outsourcing, information technology, strategic alliances, and the network economy.

In its early stages, a small business may choose not to create a formal organization chart. However, organization must exist even without a chart so that the business can be successful. Most small businesses find organization charts to be useful because they help the owner or the manager track growth and change in the organizational structure.[80] The real challenge is to create an organizational chart that reflects the real world. Small businesses have a definite advantage here because their size allows for more flexibility and manageability.

Video Clip 13.2 Burn Your Org Chart

Not all organizational charts reflect the real world.

Formal authority is “the right to give orders and set policy.”[81] It is organized according to a hierarchy, typically expressed in the organization chart, where one manager may have authority over some employees while being subject to the formal authority of a superior at the same time. Formal authority also encompasses the allocation of an organization’s resources to achieve its objectives.[82][83] The position on the organization chart will be indicative of the amount of authority and formal power held by a particular individual.

Two major types of authority that the small business owner should understand are line and staff. These authorities reflect the existing relationships between superiors and subordinates.[84] Line authority refers to having direct authority over lower positions in the hierarchy. “A manager with line authority is the unquestioned superior for all activities of his or her subordinates.”[85] The day-to-day tasks of those with line authority involve working directly toward accomplishing an organization’s mission, goals, and objectives.[86] Examples of positions with line authority are the president, the vice president of operations, and the marketing manager. In a small business, the owner or the top manager will have line authority over his or her subordinates. The extent of line authority beyond the owner or the top manager will depend on the size of the business and the organizational vision of the owner.

Staff authority is advisory only. There is no authority to take action (except when someone is a manager of a staff function, e.g., human resources), and there is no responsibility for revenue generation. Someone with staff authority assists those with line authority as well as others who have staff authority. Examples of staff authority are human resources, legal, and accounting, each of which is relevant to a small business. Staff personnel can be extremely helpful in improving the effectiveness of line personnel. Unfortunately, staff personnel are often the first to go when cutbacks occur. As a small business grows, a decision may be made to add staff personnel because the most significant factor in determining whether or not to add personnel is the size of a business. The larger the organization, the greater the need and the ability to hire staff personnel to provide specialized expertise.[87] Small businesses, however, may prefer to hire outside service providers for staff functions such as legal and accounting services because it would be difficult to keep such people busy full time. Remember, cash flow is king.

Centralization and Decentralization

Centralization and decentralization are about the amount of authority to delegate. Centralization means that little or no authority and job activities are delegated to subordinates. A relatively small number of line managers make the decisions and hold most of the authority and power. Decentralization is the opposite. Authority and job activities are delegated rather than being held by a small management group.[88] [89]

Depending on various factors, organizations move back and forth on the centralization-decentralization continuum. For example, managing a crisis requires more centralized decision making because decisions need to be made quickly.[90] A noncrisis or a normal work situation would favor decentralized decision making and encourages employee empowerment and delegated authority.[91] There are no universally accepted guidelines for determining whether a centralized or a decentralized approach should be used. It has been noted, however, that, “the best organizations are those that are able to shift flexibly from one level of centralization to another in response to changing external conditions.” [92] Given the flexibility and the responsiveness of small businesses that originate from their size, any movement that is needed along the centralization-decentralization continuum will be much easier and quicker.

Guidelines for Organizing

Several management principles can be used as guidelines when designing an organizational structure. Although there are many principles to consider, the focus here is on unity of command, division of work, span of control, and the scalar principle. These principles are applicable to small businesses although, as has been said earlier, they should not be seen as etched in stone. They can be modified or ignored altogether depending on the business, the situation at hand, and the experience of management.[93] [94]

Unity of Command

Unity of command means that no subordinate has more than one boss. Each person in a business should know who gives him or her the authority to make decisions and do the job. Having conflicting orders from multiple bosses will create confusion and frustration about which order to follow and result in contradictory instructions.[95] In addition, violating the unity of command will undermine authority, divide loyalty, and create a situation in which responsibilities can be evaded and work efforts will be duplicated and overlapping. Abiding by the unity of command will provide discipline, stability, and order, with a harmonious relationship—relatively speaking, of course—between superior and subordinate.[96] Unity of command makes the most sense for everyone, but it is violated on a regular basis.

Division of Labor

The division of labor is a basic principle of organizing that maintains that a job can be performed much more efficiently if the work is divided among individuals and groups so that attention and effort are focused on discrete portions of the task—that is, the jobholder is allowed to specialize.[97] [98] The result is a more efficient use of resources and greater productivity. As mentioned earlier, small businesses are commonly staffed with people who wear multiple hats, including the owner. However, the larger the business, the more desirable it will be to have people specialize to improve efficiency and productivity. To do otherwise will be to slow down processes and use more resources than should be necessary. This will have a negative impact on the bottom line.

Span of Control

Span of control (span of management) refers to the number of people or subordinates that a manager supervises. The span of control typically becomes smaller as a person moves up the management hierarchy. There is no magic number for every manager. Instead, the number will vary based on “The abilities of both the manager and the subordinates, the nature of the work being done, the location of the employees, and the need for planning and coordination.”[99] The growing trend is to use wider spans of control. Companies are flattening their structures by reducing their layers of management, particularly middle management. This process has increased the decision-making responsibilities that are given to employees.[100][101] [102] As a small business grows, there will likely be more management hierarchy unless the small business owner is committed to a flatter organization. Either approach will have implications for span of control.

Scalar Principle

The scalar principle maintains “that authority and responsibility should flow in a clear, unbroken line from the highest to the lowest manager.”[103] Abiding by this principle will result in more effective decision making and communication at various levels in the organization. Breaking the chain would result in confusion about relationships and employee frustration. Following this principle is particularly important to small businesses because the tendency may otherwise be to operate on a more informal basis because of the size of the business. This would be a mistake. Even a two-person business should pay attention to the scalar principle.

Types of Organization Structures

Knowledge about organization structures is important for a small business that is already up and running as well as a small business in its early stages. Organizations are changing every day, so small business owners should be flexible enough to change the structure over time as the situation demands, perhaps by using the contingency approach. “The contingency approach to the structure of current organizations suggests there is no ‘one best’ structure appropriate for every organization. Rather, this approach contends the ‘best’ structure for an organization fits its needs for the situation at the time.”[104] If a small business employs fewer than fifteen people, it may not be necessary to worry too much about its organizational structure. However, if the plans for the business include hiring more than fifteen people, having an organizational structure makes good sense because it will benefit a company’s owner, managers, employees, investors, and lenders.[105] There are many structure options. Functional, divisional, matrix, and network or virtual structures are discussed here.

Functional Structure

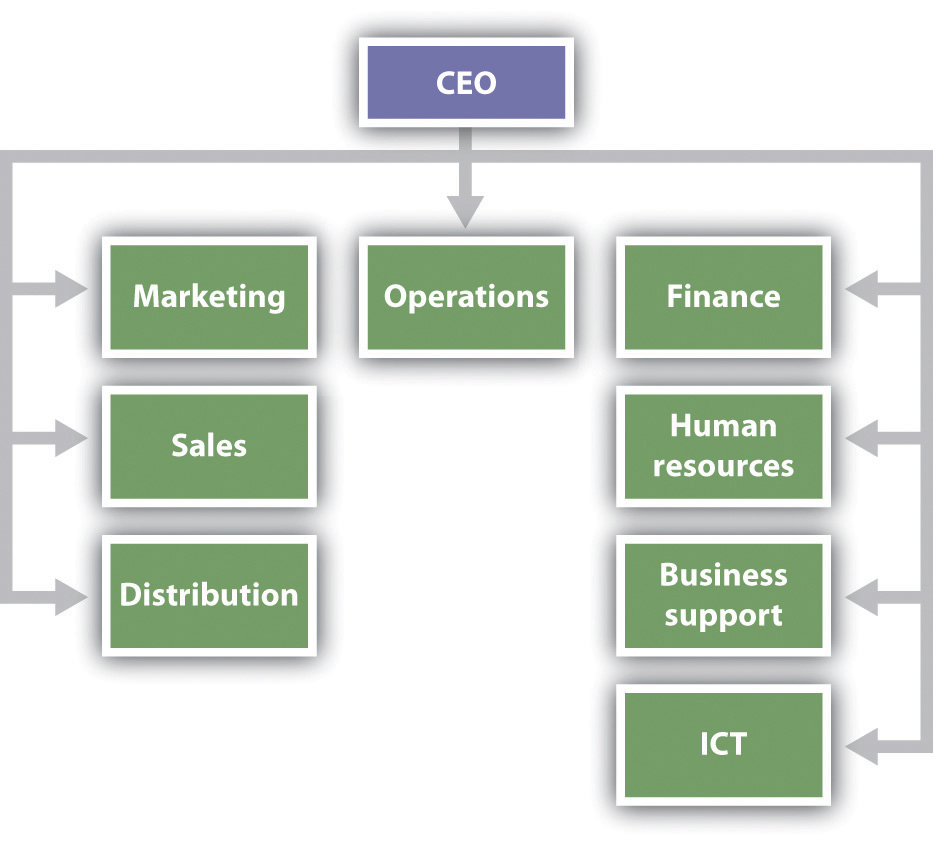

The functional structure is overwhelmingly the choice of business start-ups and is probably the most common structure used today. This structure organizes a business according to job or purpose in the organization and is most easily recognized by departments that focus on a single function or goal. (See Figure 13.6 “An Example of a Functional Structure” for an example of a functional structure.) A start-up business is not likely to have an organization that looks like this. There may be only one or two boxes on it, representing the founder and his or her partner (if applicable).[106] As a small business grows, the need for additional departments will grow as well.

Figure 13.6 An Example of a Functional Structure [107]

The functional structure gives employees and their respective departments clear objectives and purpose for their work. People in accounting can focus on improving their knowledge and skills to perform that work. This structure has also been shown to work well for businesses that operate in a relatively stable environment.[108] [109]

At the same time, the functional structure can create divisions between departments if conflict occurs,[110] and it can become an obstruction if the objectives and the environment of the business require coordination across departments.[111]

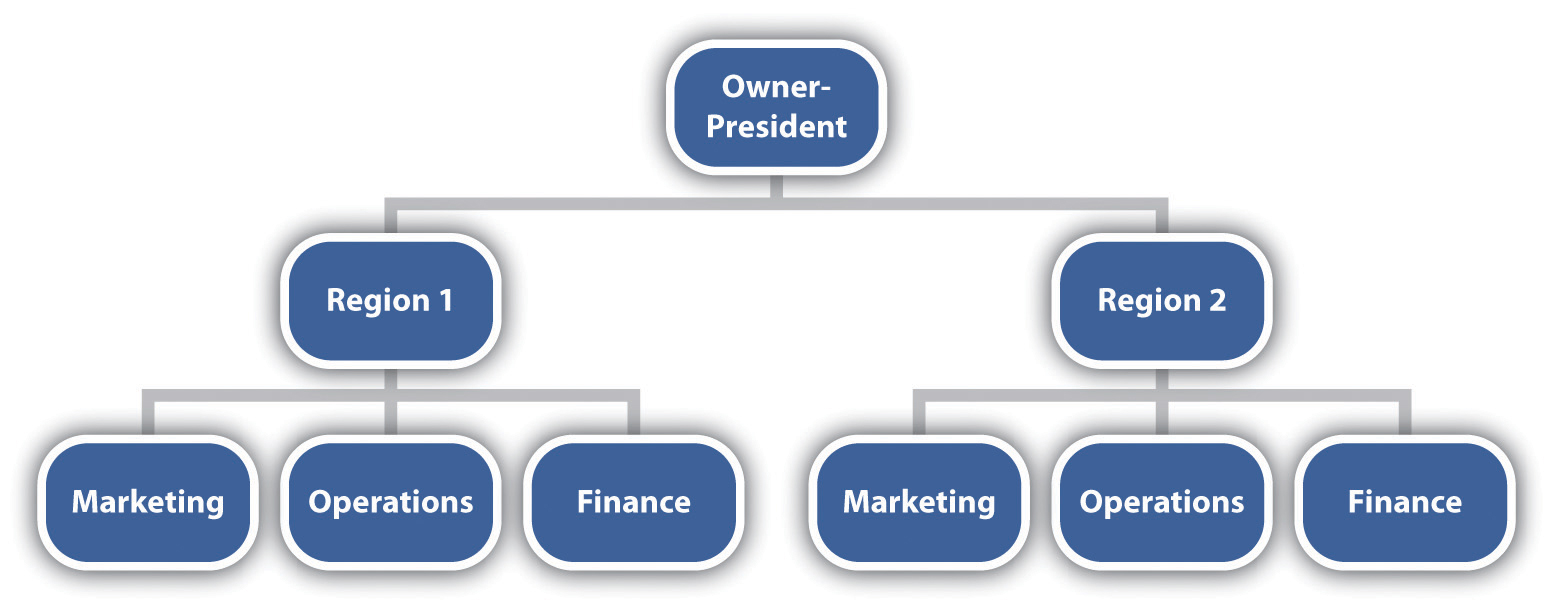

Divisional Structure

The divisional structure can be seen as a decentralized version of the functional structure. The functions still exist in the organization, but they are based on product, geographic area or territory, or customer. Each division will then have its own functional department(s).[112] (See Figure 13.7 “An Example of a Divisional Structure” for an example of a divisional structure.)

Figure 13.7 An Example of a Divisional Structure

The divisional structure can work well because it focuses on individual geographic regions, customers, or products. This focus will enable greater efficiencies of operation and the building of “A common culture and esprit de corps that contributes both to higher morale and a better knowledge of the division’s portfolio.” [113] There are, of course, disadvantages to this structure. Competing divisions may turn to office politics, rather than strategic thinking, to guide their decision making, and divisions may become so compartmentalized as to lead to product incompatibilities. [114]

As a small business starts to grow in the diversity of its products, in the geographic reach of its markets, or in its customer bases, there is an evolution away from the functional structure to the divisional structure. However, significant growth would be needed before the divisional structure should be put into place.

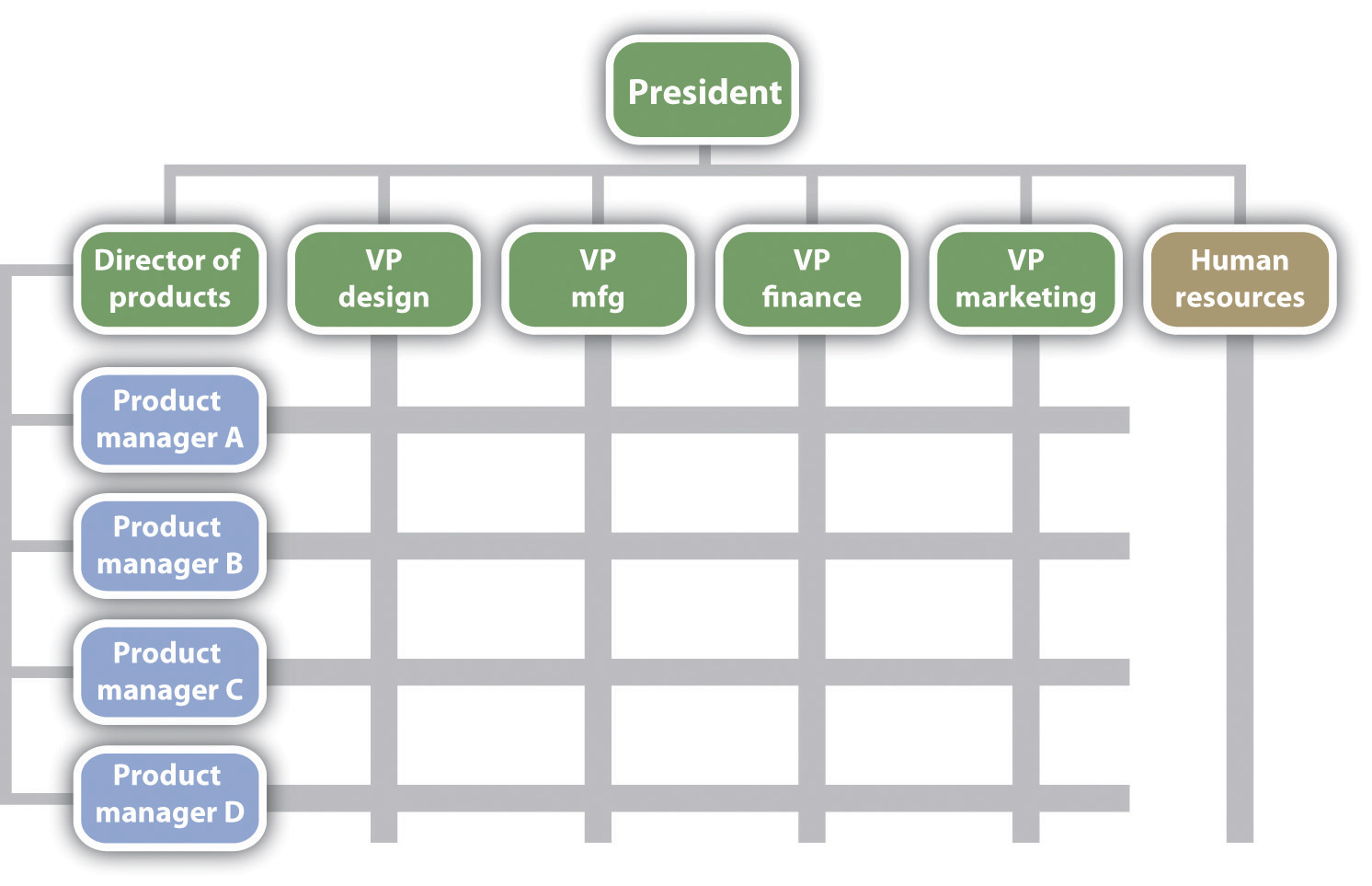

Matrix Structure

The matrix structure combines elements of the functional and the divisional structures, bringing together specialists from different areas of a business to work on different projects on a short-term basis. Each person on the project team reports to two bosses: a line manager and a project manager. (See Figure 13.8 “An Example of a Matrix Structure” for an example of a matrix structure.) The matrix structure, popular in high-technology, multinational, consulting, and aerospace firms and hospitals, offers several key advantages, including the following: flexibility in assigning specialists, flexibility in adapting quickly to rapid environmental changes, the ability to focus resources on major products and problems, and creating an environment where there is a higher level of motivation and satisfaction for employees.[115] [116] [117] The disadvantages include the following: the violation of the “one boss” principle (unity of command) because of the dual lines of authority, responsibility, and accountability;[118] employee confusion and frustration from reporting to two bosses; power struggles between the first-line and the project managers; too much group decision making; too much time spent in meetings; personality clashes; and undefined personal role.s[119] [120] The disadvantages notwithstanding, many companies with multiple business units, operations in multiple countries, and distribution through multiple channels have discovered that the effective use of a matrix structure is their only choice.[121]

Figure 13.8 An Example of a Matrix Structure [122]

The matrix structure is for project-oriented businesses, such as aerospace, construction, or small manufacturers of the job-shop variety (producers of a wide diversity of products made in small batches).

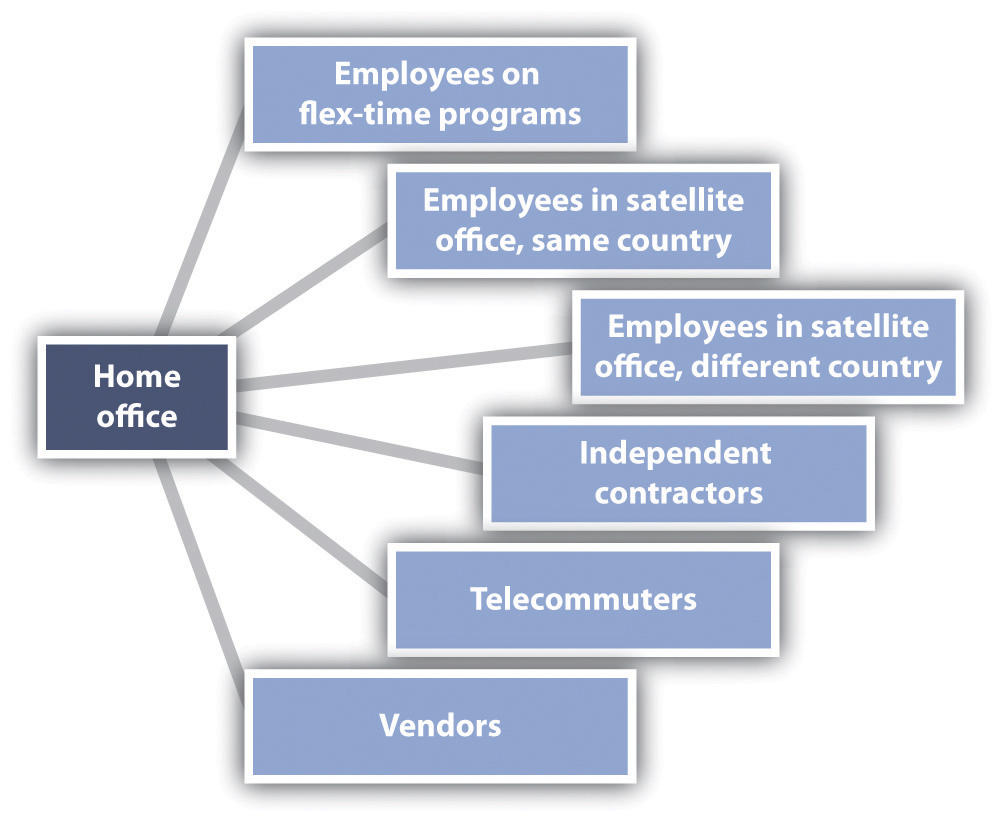

Virtual Organization

The virtual organization (or network organization) is becoming an increasingly popular business structure as a means of addressing critical resource, personnel, and logistical issues. (See Figure 13.9 “An Example of a Virtual Organization” for an example of a virtual organization.) Administration is the primary function performed; other functions—such as marketing, engineering, production, and finance—are outsourced to other organizations or individuals. Individual professionals may or may not share office space, the organization is geographically distributed, the members of the organization communicate and coordinate their work through information technology, and there is a high degree of informal communication. The barriers of time and location are removed. [123] [124] [125]

Figure 13.9 An Example of a Virtual Organization [126]

The positives associated with a virtual organization include reduced real-estate expenses, increased productivity, higher profits, improved customer service, access to global markets, environmental benefits (such as reduced gas mileage for employees, which contributes to reduced auto emissions), a wider pool of potential employees, and not needing to have all or some of the relevant employees in the same place at the same time for meetings or delivering services.[127][128] The negatives include setup costs; some loss of cost efficiencies; cultural issues (particularly when working in the global arena); traditional managers not feeling secure when their employees are working remotely, particularly in a crisis; feelings of isolation because of the loss of the camaraderie of the traditional office environment; and a lack of trust.[129] [130]

The virtual organization can be quite attractive to small businesses and start-ups. By outsourcing much of the operations of a business, costs and capital requirements will be significantly reduced and flexibility enhanced. Given the lower capital requirements of a virtual business, some measures of profitability (e.g., return on investment [ROI] and return on assets [ROA]), would be significantly increased. This makes a business much more financially attractive to potential investors or banks, which might provide funding for future growth. ROI “is a performance measure used to evaluate the efficiency of an investment or to compare the efficiency of a number of investments.”[131] ROA is “an indicator of how profitable a company is relative to its assets…[giving] an idea as to how efficient management is at using its assets to generate earnings.”[132]

Creating an Effective Business Organization Structure

Thinking and rethinking the business organization structure is important for all businesses—large or small. Conditions, products, and markets change. It is important to be flexible in creating a business structure that will best allow a business to operate effectively and efficiently. Each of the following should be considered:

- Competitors. Make an educated guess of the structure of competitors. Try to find out what works for them. Look at their reporting line structures and their procurement, production, marketing, and management systems. Perhaps there are some good ideas to be had.

- Industry. Is there a standard in an industry? Perhaps an industry lends itself to flexible organization structures, or perhaps more hierarchical structures are the norm. For example, auto manufacturers are usually set up regionally.

- Compliance or legal requirements. If an industry is regulated, certain elements may be required in the business structure. Even if an industry is not regulated, there may be compliance issues associated with employing a certain number of employees.

- Investors and lending sources. Having a business organization structure will give potential investors and funding institutions a window into how the business organizes its operations. The structure also lets investors and lenders know what kind of talent is needed, how soon they will be needed, and how the business will find and attract them.[133]

Key Takeaways

- Organizations are changing every day, so small business owners should be flexible enough to change their structure over time as the situation demands.

- The functional structure is overwhelmingly the choice of business start-ups and is probably the most commonly used structure today.

- The functional structure organizes a business according to the job or the purpose in the organization and is most easily recognized by departments that focus on a single function or goal.

- The divisional structure is a decentralized version of the functional structure. The functions still exist, but they are based on product, geographic area or territory, or customer.

- As a small business starts to grow, there is an evolution away from the functional to the divisional structure. However, significant growth is required before the divisional structure is put into place.

- The matrix structure brings specialists from different areas of a business together to work on different projects for a short-term basis. This structure is for project-oriented businesses, such as aerospace, construction, or small manufacturers.

- In the virtual structure, administration is the primary function performed, with other functions—such as marketing, engineering, production, and finance—outsourced to other companies or individuals. This structure can be quite attractive to small businesses and start-ups.

- Creating an effective business organization structure should take the competition, the industry, compliance or legal requirements, investors, and lending sources into consideration.

Exercises

- Select two small businesses that market two very different products, for example, a small manufacturer and a restaurant. Contact the manager of each business and conduct a fifteen-minute interview about the organizational structure that has been chosen. Ask each manager to describe the existing organizational structure (drawing an organization chart), explain why that structure was chosen, and reflect on the effectiveness and efficiency of the structure. Also ask each manager whether any thoughts have been given to changing the existing structure.

- Frank Rainsford has been, in effect, the CEO of Frank’s All-American BarBeQue since its inception. His major role has been that of restaurant manager, receiving support from his assistant manager Ed Tobor for the last fourteen years. Frank has two children, a son and daughter, who both worked in the restaurant as teenagers. His daughter has worked periodically at the restaurant since she graduated from high school. Frank’s son, who recently lost his job, has returned to work for his father. The son produced several plans to expand the business, including the opening of a second restaurant and the extensive use of social media. After careful consideration, Frank has decided to open a second restaurant, but this has presented him with a major problem—how to assign responsibilities to personnel. His son wants to be designated the restaurant manager of the second restaurant and made the vice president of marketing. Ed Tobor also wants to be the manager of the new restaurant. His daughter has expressed an interest in being the manager of either restaurant. How should Frank resolve this problem?

Legal Forms of Organization for the Small Business

Learning Objectives

- Understand the different legal forms that a small business can take.

- Explain the factors that should be considered when choosing a legal form.

- Understand the advantages and disadvantages of each legal form.

- Explain why the limited liability company may be the best legal structure for many small businesses.

Every small business must select a legal form of ownership. The most common forms are sole proprietorship, partnership, and corporation. A limited liability company (LLC) is a relatively new business structure that is now allowed by all fifty states. Before a legal form is selected, however, several factors must be considered, not the least of which are legal and tax options.

Factors to Consider

The legal form of the business is one of the first decisions that a small business owner will have to make. Because this decision will have long-term implications, it is important to consult an attorney and an accountant to help make the right choice. The following are some factors the small business owner should consider before making the choice:[134] [135]

- The owner’s vision. Where does the owner see the business in the future (size, nature, etc.)?

- The desired level of control. Does the owner want to own the business personally or share ownership with others? Does the owner want to share responsibility for operating the business with others?

- The level of structure. What is desired—a very structured organization or something more informal?

- The acceptable liability exposure. Is the owner willing to risk personal assets? Is the owner willing to accept liability for the actions of others?

- Tax implications. Does the owner want to pay business income taxes and then pay personal income taxes on the profits earned?

- Sharing profits. Does the owner want to share the profits with others or personally keep them?

- Financing needs. Can the owner provide all the financing needs or will outside investors be needed? If outside investors are needed, how easy will it be to get them?

- The need for cash. Does the owner want to be able to take cash out of the business?

The final selection of a legal form will require consideration of these factors and tradeoffs between the advantages and disadvantages of each form. No choice will be perfect. Even after a business structure is determined, the favorability of that choice over another will always be subject to changes in the laws.[136]

Sole Proprietorship

A sole proprietorship is a business that is owned and usually operated by one person. It is the oldest, simplest, and cheapest form of business ownership because there is no legal distinction made between the owner and the business (see Table 13.1 “Sole Proprietorships: A Summary of Characteristics”). Sole proprietorships are very popular, comprising 72 percent of all businesses and nearly $1.3 trillion in total revenue.[137] Sole proprietorships are common in a variety of industries, but the typical sole proprietorship owns a small service or retail operation, such as a dry cleaner, accounting services, insurance services, a roadside produce stand, a bakery, a repair shop, a gift shop, painters, plumbers, electricians, and landscaping services.[138] Clearly, the sole proprietorship is the choice for most small businesses.

Table 13.1 Sole Proprietorships: A Summary of Characteristics [139] [140] [141] [142]

| Liability | Taxes | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unlimited: owner is responsible for all the debts of the business. | No special taxes; owner pays taxes on profits; not subject to corporate taxes |

|

|

Partnership

A partnership is two or more people voluntarily operating a business as co-owners for profit. Partnerships make up more than 8 percent of all businesses in the United States and more than 11 percent of the total revenue.[143] Like the sole proprietorship, the partnership does not distinguish between the business and its owners (see Table 13.2 “Partnerships: A Summary of Characteristics”). There should be a legal agreement that “sets forth how decisions will be made, profits will be shared, disputes will be resolved, how future partners will be admitted to the partnership, how partners can be bought out, and what steps will be taken to dissolve the partnership when needed.”[144]

There are two types of partnerships. In the general partnership, all the partners have unlimited liability, and each partner can enter into contracts on behalf of the other partners. A limited partnership has at least one general partner and one or more limited partners whose liability is limited to the cash or property invested in the partnership. Limited partnerships are usually found in professional firms, such as dentists, lawyers, and physicians, as well as in oil and gas, motion-picture, and real-estate companies. However, many medical and legal partnerships have switched to other forms to limit personal liability.[145] [146] [147]

Before creating a partnership, the partners should get to know each other. According to Michael Lee Stallard, cofounder and president of E Pluribis Partners, a consulting firm in Greenwich, Connecticut, “The biggest mistake business partners make is jumping into business before getting to know each other…You must be able to connect to feel comfortable expressing your opinions, ideas and expectations.”[148]

Table 13.2 Partnerships: A Summary of Characteristics [149] [150] [151] [152] [153]

| Liability | Taxes | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unlimited for general partner; limited partners risk only their original investment. | Individual taxes on business earnings; no income taxes as a business |

|

|

Corporation

A corporation “is an artificial person created by law, with most of the legal rights of a real person. These include the rights to start and operate a business, to buy or sell property, to borrow money, to sue or be sued, and to enter into binding contracts”.[154] (see Table 13.3 “Corporations: A Summary of Characteristics”). Corporations make up 20 percent of all businesses in the United States, but they account for almost 90 percent of the revenue.[155] Although some small businesses are incorporated, many corporations are extremely large businesses—for example, Walmart, General Electric, Procter & Gamble, and Home Depot. Recent data show that only about one-half of the small business owners in the United States run incorporated businesses.[156]

Scott Shane, author of The Illusions of Entrepreneurship (Yale University Press, 2010), argues that small businesses that are incorporated have a much higher rate of success than sole proprietorships, outperforming unincorporated small businesses in terms of profitability, employment growth, sales growth, and other measures.[157] Shane maintains that being incorporated may not make sense for “tiny little businesses” because the small amount of risk may not be worth the complexity. However, Deborah Sweeney, incorporation expert for Intuit, disagrees, saying that “even the smallest eBay business has a risk of being sued” because shipping products around the country or the world can create legal problems if a shipment is lost.[158] Ultimately, it is the small business being successful that may be the biggest factor for the owner to move from a sole proprietorship to a corporation.

Table 13.3 Corporations: A Summary of Characteristics [159] [160] [161] [162]

| Liability | Taxes | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limited; | multiple taxation |

|

|

Limited Liability Company

The limited liability company (LLC) is a relatively new form of business ownership that is now permitted in all fifty states, although the laws of each state may differ. The LLC is a blend of a sole proprietorship and a corporation: the owners of the LLC have limited liability and are taxed only once for the business.[163] The LLC provides all the benefits of a partnership but limits the liability of each investor to the amount of his or her investment (see Table 13.4 “Limited Liability Companies: A Summary of Characteristics”). “LLCs were created to provide business owners with the liability protection that corporations enjoy without the double taxation.”[164]

According to Carter Bishop, a professor at Suffolk University Law School, who helped draft the uniform LLC laws for several states, “There’s virtually no reason why a small business should file as a corporation, unless the owners plan to take the business public in the near future.”[165] In the final analysis, the LLC business structure is the best choice for most small businesses. The owners will have the greatest flexibility, and there is a liability shield that protects all owners. [166]

Table 13.4 Limited Liability Companies: A Summary of Characteristics [167] [168][169] [170] [171]

| Liability | Taxes | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limited; | owners taxed at individual income tax rate |

|

|

Key Takeaways

- Every small business must select a legal form of ownership. It is one of the first decisions that a small business owner must make.

- The most common forms of legal structure are the sole proprietorship, the partnership, and the corporation. An LLC is a relatively new business structure.

- When deciding on a legal structure, every small business owner must consider several important factors before making the choice.

- The sole proprietorship is the oldest, simplest, and cheapest form of business ownership. This business structure accounts for the largest number of businesses but the lowest amount of revenue. This is the choice for most small businesses.

- A partnership is two or more people voluntarily operating a business as co-owners for profit. There are general partnerships and limited partnerships.

- A corporation is an artificial person with most of the legal rights of a real person. Corporations make up about 20 percent of all businesses in the United States, but they account for almost 90 percent of the revenue.

- Small businesses that are incorporated outperform unincorporated small businesses in terms of profitability, employment growth, sales growth, and other measures.

- The LLC is a hybrid of a sole proprietorship and a corporation. It is the best choice for most small businesses.

Exercises

- Select three small businesses of different sizes: small, medium, and large. Interview the owners, asking each about the legal structure that the owner chose and why. If any of the businesses are sole proprietorships, ask the owner if an LLC was considered. If not, try to find out why it was not considered.

- Frank’s BarBeQue is currently a sole proprietorship. Frank’s son, Robert, is trying to persuade his father to either incorporate or become an LLC. Assume that you are Robert. Make a case for each legal structure and then make a recommendation to Frank. It is expected that you will go beyond the textbook in researching your response to this assignment.

People

Learning Objectives

- Understand the complexities of hiring, retaining, and terminating employees.

- Be aware of the laws that apply to businesses of all sizes and specifically to small businesses of certain sizes.

- Understand outsourcing: what it is; when it is a good idea; and when it is a bad idea.

- Describe ways to improve office productivity.

The term human resources has been deliberately avoided in this section. This term is more appropriate for large bureaucratic organizations that tend to view their personnel as a problem to be managed. Smaller and midsize enterprise personnel, however, are not mere resources to be managed. They should not be seen as cogs in a machine that are easily replaceable. Rather, they are people to be cultivated because they are the true lifeblood of the organization.

Many small businesses operate with no employees. The sole proprietor handles the whole business individually, perhaps with help from family or friends from time to time. Deciding to hire someone will always be a big leap because there will be an immediate need to worry about payroll, benefits, unemployment, and numerous other details.[172] A small business that looks to grow will face the hiring decision again and again, and additional decisions about compensation, benefits, retention, training, and termination will become necessary. Other issues of concern to a growing small business or a small business that wants to stay pretty much where it is include things such as outsourcing, how to enhance and improve productivity, and legal matters.

Hiring New People

All businesses want to attract, develop, and retain enough qualified employees to perform the activities necessary to accomplish the organizational objectives of the business.[173] Although most small businesses will not have a department dedicated to performing these functions, these functions must be performed just the same. The hiring of the first few people may end up being pretty simple, but as the hiring continues, there should be a more formal hiring process in place.

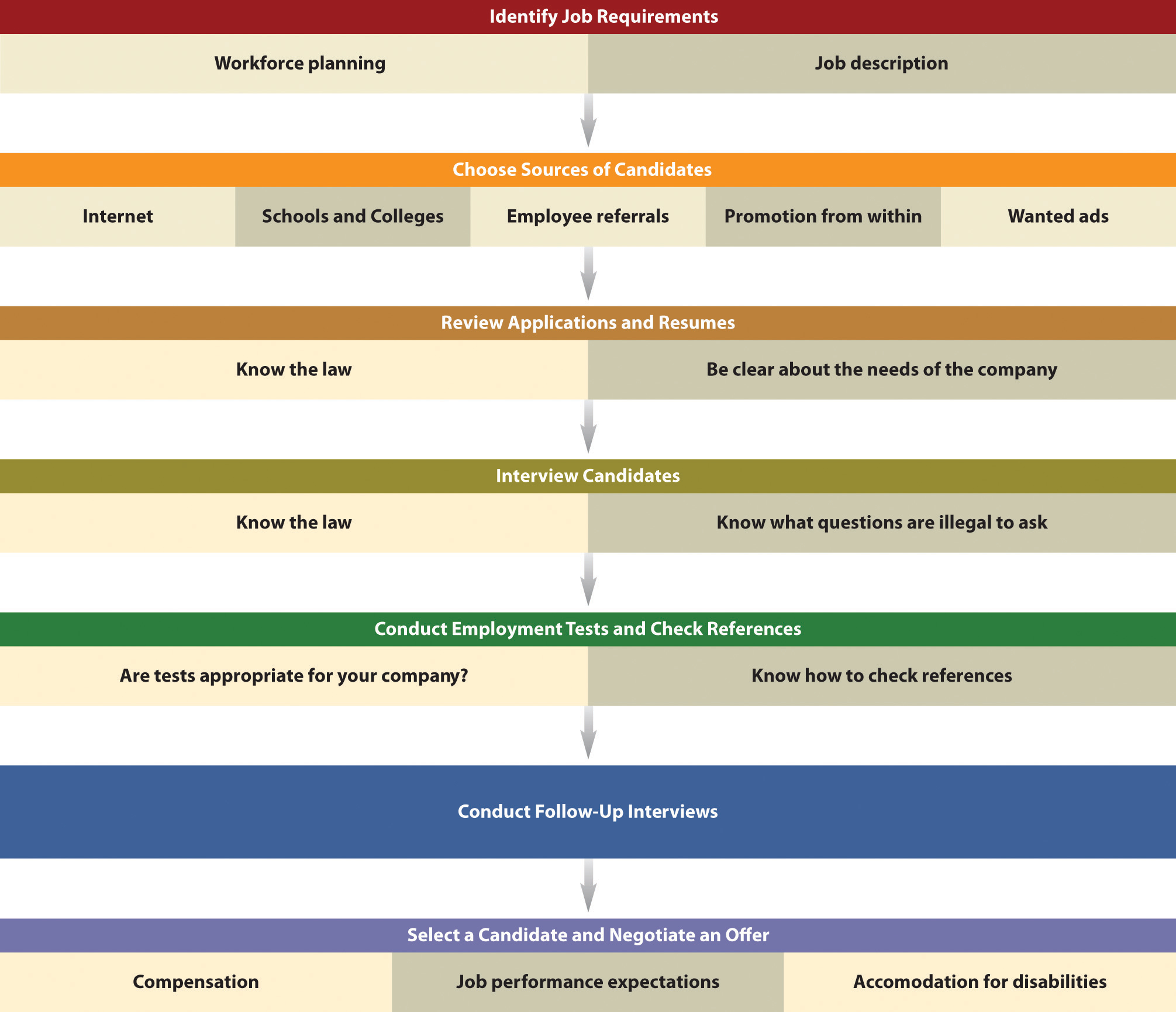

Figure 13.10 “Steps in the Hiring Process” illustrates the basics of any hiring process, whether for a sole proprietorship or a large multinational corporation.

Figure 13.10 Steps in the Hiring Process [174]

Identify Job Requirements

A small business owner should not proceed with hiring anyone until he or she has a clear idea of what the new hire will do and how that new hire will help attain the objectives of the business. Workforce planning, the “process of placing the right number of people with the right skills, experiences, and competencies in the right jobs at the right time,”[175] is a way to do that. The scope of this planning will be very limited when a business is very small, but as a business grows, it will take on much greater importance. Doing things right with the first new hire will establish a strong foundation for hiring in the future. Forecasting needs for new people, both current and future, is part of workforce planning. No forecast is perfect, but it will provide a basis on which to make hiring decisions.

As an employer, every small business should prepare a job description before initiating the recruitment process. A good job description describes the major areas of an employee’s job or position: the duties to be performed, who the employee will report to, the working conditions, responsibilities, and the tools and equipment that must be used on the job.[176] It is important not to create an inflexible job description because it will prevent the small business owner and the employees from trying anything new and learning how to perform their jobs more productively.[177]

Choose Sources of Candidates

Because hiring a new employee is an expensive process, it is important to choose sources that have the greatest potential for reaching the people who will most likely be interested in what a small business has to offer. Unfortunately, it is not always possible to know what those sources are, so selecting a mix of sources makes good sense.

- Internet. The Internet offers a wealth of places to advertise a job opportunity. Monster.com, CareerBuilder.com, and LinkedIn.com are among the largest and most well-known sites, but there may be local or regional job sites that might work better, particularly if a business is very small. A business will not have the resources to bring people in from great distances. If a business has a Facebook or a Twitter presence, this is another great place to let people know about job openings. There may also be websites that specialize in particular occupations.

- Schools and colleges. Depending on the nature of the job, local schools and colleges are great sources for job candidates, particularly if the job is part time. Full-time opportunities may be perfect for the new high school or college graduate. It would be worth checking out college alumni offices as well because they often offer job services.

- Employee referrals. Referrals are always worth consideration, if only on a preliminary basis. The employee making the referral knows the business and the person being referred. Going this route can significantly shorten the search process…if there is a fit.

- Promotion from within. Promoting from within is a time-honored practice. The owner sends a positive signal to employees that there is room for advancement and management cares about its employees. It is significantly less costly and quicker than recruiting outside, candidates are easier to assess because more information is available, and it improves morale and organization loyalty.[178] On the downside, there may be problems between the person who is promoted and former coworkers, and the organization will not benefit from the fresh ideas of someone hired from the outside.

- Want ads. Want ads can be very effective for a small business, especially if a business is looking locally or regionally. The more dynamic the want ad, the more likely it will attract good candidates. Newspapers and local-reach magazines might be a business’s first thoughts but also consider advertising in the newsletters of relevant professional organizations and at the career services offices of local colleges, universities, and technical colleges.

Review Applications and Résumés

When looking for the best qualified candidates, be very clear about the objectives of the business and the associated reason(s) for hiring someone new. It is also critical to know the law. Some examples are provided here. This would be a good time to consult with a lawyer to make sure that everything is done properly.

- Employee registration requirement. All US employers must complete and retain Form I-9 for each individual, whether a citizen or a noncitizen, hired for employment in the United States. The employer must verify employment eligibility and identity documents presented by the employee.[179]

- The Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Civil Rights Act of 1991, and the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972. Attempt to provide equal opportunities for employment with regard to race, religion, age, creed, gender, national origin, or disability.[180] The closest Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) district office should be contacted for specific information.

- Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986. This law places a major responsibility on employers for stopping illegal immigration.

Labor Laws Governing Employers

The following is a brief synopsis of some of the federal statutes governing employers that may apply to a small business. In many instances, they are related to the size of the business.[181] There are definite advantages to staying small.

The following laws apply no matter the size of the business:

- Fair Labor Standards Act

- Social Security

- Federal Insurance Contributions Act

- Medicare

- Equal Pay Act

- Immigration Reform and Control Act

- Federal Unemployment Tax Act

This additional law applies if a business has more than ten employees:

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration Act

The following additional laws apply if a business has more than fourteen employees:

- Title VII Civil Rights Act

- Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

- Pregnancy Discrimination Act

The following additional laws apply if a business has more than nineteen employees:

- Age Discrimination in Employment Act

- Older Worker Benefit Protection Act

- Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act

This additional law applies if a business has more than forty-nine employees:

- Family Medical Leave Act

The following additional laws apply if a business has more than ninety-nine employees:

- Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act

- Employee Retirement Income Security Act

Interview Candidates

Just as knowing the law is important when reviewing applications and résumés, it is also important when interviewing candidates. Several interview questions are illegal to ask—for example, “Do you have dependable child care in place?” and “Do you rent or own your own home?”[182] In general, the off-limit topics in most employment interviews include religion, national origin, race, marital status, parental status, age, disability, gender, political affiliation, criminal records, and other personal information such as financial and credit history.[183] In short, keep the interview focused on the job, its requirements, and the qualifications of the candidate.[184]

Conduct Employment Tests and Check References

Selection tests have been used to screen applicants for more than one hundred years.[185] An effective testing program can improve accuracy in selecting employees; provide an objective means for comparing candidates; and provide information about training, development, or counseling needs. These advantages must be carefully weighed against the disadvantages: the fallibility of tests, the fact that tests can never measure everything, and many tests discriminate against minorities.[186] Each small business owner must decide whether employment tests make sense for his or her business. However, Daniel Kehrer of Work.com claims that employee testing is essential to reducing employee turnover for small businesses because preemployment screens are four times greater at predicting employee success than interviews. He notes further that high turnover rates are much more expensive for small businesses than large companies.[187] Just be sure that all employment tests can be linked to a business necessity.[188]

Checking references is a much more difficult proposition. It is a good idea to check references after the interview to objectively evaluate the candidate’s qualifications, experience, and other information presented during the interview. Not checking references can result in poor hiring choices.[189]

Unfortunately, many former employers are reluctant to reveal anything other than an employee’s date of hire and departure and job title,[190] but others may be willing to discuss an employee’s job performance, work ethic, attendance, attitude, and other things that may be important to the prospective employer.[191]

As important as it is to check references, it is a process that is fraught with legal risk, so check with an attorney before moving forward.

Select a Candidate and Negotiate an Offer

After any desired follow-up interviews are conducted, it is time to select a candidate and negotiate an offer. There are three main issues to consider: compensation, job performance and expectations, and accommodations for disabilities.

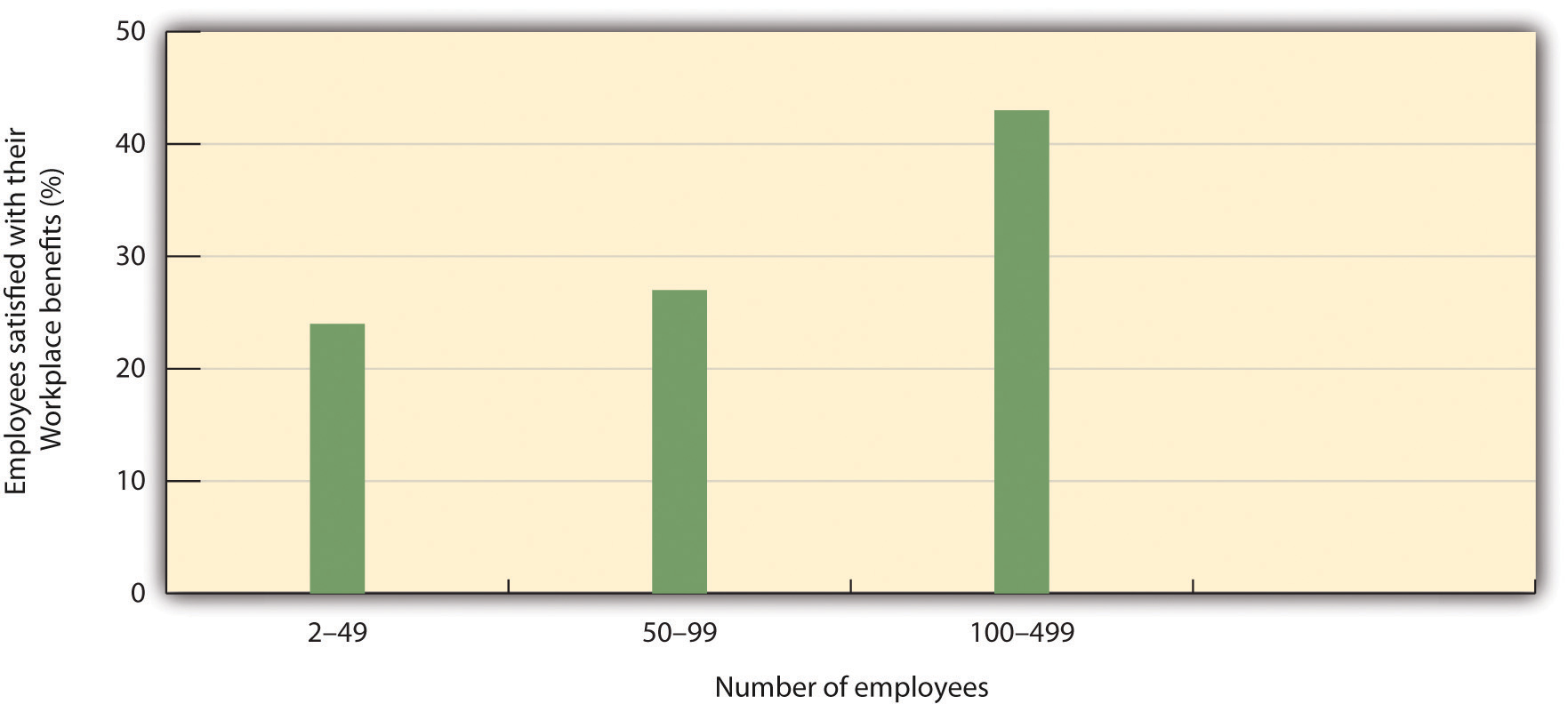

Wages and salaries are often used interchangeably, however they are different. Wages are payments based on an hourly pay rate or the amount of output. Production employees, maintenance workers, retail salespeople (sometimes), and part-time workers are examples of employees who are paid wages.[192] Salaries are typically calculated weekly, biweekly, or monthly. They are usually paid to office personnel, executives, and professional employees.[193] Every small business should do its best to offer competitive wages and salaries, but a small business will generally not be able to offer wages and salaries that are comparable to those offered by large corporations and government. Employee benefits such as health and disability insurance, sick leave, vacation time, child and elder care, and retirement plans, are paid entirely or in part by the company; they represent a large component of each employee’s compensation.[194] Most employees have come to expect a good benefits program, even in a small business, so “the absence of a program or an inadequate program can seriously hinder a company’s ability to attract and keep good personnel.”[195] Not surprisingly, small businesses are also not in a position to offer the same level of benefits that can be offered by large corporations and the government. However, small businesses can still offer a good benefits program if it includes some or all the following elements: health insurance, disability insurance, life insurance, a retirement plan, flexible compensation, leave, and perks.[196] In addition, small businesses can offer benefits that only a small business can offer—for example, the flexibility to dress casually, half days on Friday, and bringing one’s pet to work. Other ideas include gym memberships or lunch programs. These things have proven to increase employee loyalty, and they will fit the budget of even the smallest business.[197]

Set Performance Expectations

It is in the best interests of a business for prospective new employees to know and understand their performance expectations. This means that a business must determine what these expectations are. New employees should understand the goals of the organization and, as applicable, the department in which they will be working. It should also be made clear how the employee’s work can positively impact the achievement of these goals.[198]

Make Accommodations for Disabilities

If a business is hiring someone with a disability and has fifteen or more employees, it is required by the ADA (enacted in 1990) to make reasonable workplace accommodations for employees with disabilities. Though not required, businesses with fewer than fifteen employees should consider accommodations as well.

Reasonable accommodations are adjustments or modifications which range from making the physical work environment accessible to restructuring a job, providing assistive equipment, providing certain types of personal assistants (e.g., a reader for a person who is blind, an interpreter for a person who is deaf), transferring an employee to a different job or location, or providing flexible scheduling. Reasonable accommodations are tools provided by employers to enable employees with disabilities to do their jobs. For example, employees are provided with desks, chairs, phones, and computers. An employee who is blind or who has a visual impairment might need a computer which operates by voice command or has a screen that enlarges print.[199]

A tax credit is available to an eligible small business, and businesses may deduct the costs (up to $15,000) of removing an architectural barrier. Small businesses should check with the appropriate government agency before making accommodations to make sure that everything is done correctly.

Is a Business Hiring and Breeding Greedy and Selfish Employees?