Day-to-day Operations

6 Chapter 6: Icebergs and Escapes

Icebergs and Escapes

Source: Used with permission from John Bello.

John Bello and Tom Schwalm founded SoBe Beverages in Norwalk, Connecticut, in 1996. The name is an abbreviation of South Beach, the well-known upscale area in Miami, Florida. John describes SoBe as playfully irreverent, having brand equity with meaning, a cult brand that resonates in the marketplace. He attributes the company’s success to some luck, missteps by the competition, being aggressive, and tapping into a cultural shift.

SoBe tapped into a cultural shift toward healthier living and wellness and the rise of companies like General Nutrition that focused on wellness products: vitamins, supplements, minerals, and herbs. Their first product, Black Tea 3G, contained ginseng, guarana, and ginkgo. Orange Carrot, another of SoBe’s first successful products, is a blend of orange and carrot juices enhanced with calcium, chromium picolinate, and carnitine. An extensive line of other flavors was added. All ingredients were linked to specific health benefits.

The first two years of operation saw SoBe losing money, but by the end of 1997, the company was on fire. In five years, the company went from $0 to $300 million in sales, and it became a national brand. SoBe was competing effectively at a premium price. Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Arizona, and other brands took notice. Within three years, Coca-Cola was talking to SoBe about a possible strategic partnership. There were fifteen meetings, only two of which were with marketing. The rest were with corporate lawyers (John calls them “sales preventers”) and regulators. At the end of 1999, Minute Maid presented the proposal to the Coca-Cola board. Surprisingly, it was rejected. Coca-Cola saw no reason to go beyond carbonated soft drinks, and there were also some leadership issues. Back to square one.

John and Tom started looking at liquidation because of pressure from investors who wanted their money. But there were other reasons they thought about selling. They were not interested in managing a disparate group of investors—bankers, investors, and private equity companies. With 250 employees, the company was growing into something they did not want it to be—and they were not having as much fun. In 2000, the market was flattening, so with a big brand image, it was a good time to get out. They also wanted to get into larger markets, such as schools and golf clubs, but only big companies could get them into a broader marketplace. They hired an investment bank and again went into negotiations with Coca-Cola as a strategic partner. The situation became very complicated and frustrating. Ultimately, a deal with Coca-Cola was again a no-go.

All was not lost. Pepsi (and others) had expressed an interest. John made a presentation to forty people at Pepsi—rather than the multiple presentations he had to make to Coca-Cola—and within two weeks, they had a deal. SoBe was sold in 2000 to Pepsi for an impressive $370 million…a very nice return on an investment of $7 million in cash and $1 million in trade-out services. Part of the deal was that John would stay on at Pepsi for two years to manage the brand, but after one day, it was clear to him that he was not going to be managing anything. Things were moved into committee, and the corporate bureaucracy took over. John likened the experience to “Making Ho Chi Minh a general in the US Army,” that is, he had a very different way of doing things. He is independent, is unconventional, speaks his mind, and would rather do things and make them work—an approach that tends to be at odds with the culture in large corporations.

SoBe inspired a whole line of functional beverages that people like to buy to make them feel smarter, healthier, and sexier. The company helped to build careers that have lasted. John is very happy with his legacy…and with his piece of the $370 million sale price.[1]

Most textbooks on small business and entrepreneurship emphasize, quite correctly, the benefits and joys of owning and operating one’s own business. However, they often neglect to cover many of the challenges of continuing to operate a business successfully—the icebergs that can sink a business. The first half of this chapter covers one of the biggest icebergs: a natural or a man-made disaster and the disaster planning that should precede it. Being able to anticipate a disaster will contribute significantly to its effective handling so that a business can survive.

Even if a small business survives a disaster or another kind of iceberg, the owner may still wish to walk away. If a business does not survive, the owner will have no choice but to walk away. There may be other reasons forcing the owner to walk away, or escape, as well. The second half of this chapter discusses the forced escape and the other end of the spectrum—when things go so well that the business owner is ready to move on to another phase of his or her life. In both cases, an exit strategy will be required.

Icebergs

Learning Objectives

- Understand the kinds of disasters that can face a small business.

- Understand why disaster planning is important to a small business.

- Describe the process of disaster planning.

- Describe the sources of disaster assistance for small businesses.

A natural or a man-made disaster is but the tip of the iceberg. Planning for the complexity of what lies below the tip is important for every small business. Small- to medium-sized businesses are the most vulnerable in the event of a disaster.[2] It has been estimated by the US Department of Labor that 40 percent of businesses never reopen following a disaster. At least 25 percent of the remaining companies will close within two years. The Association of Records Managers and Administrators estimated that over 60 percent of small businesses that experience a major disaster close by the end of two years.[3]

Given these odds, planning for disaster recovery makes great sense—even if, in the end, walking away makes the most sense. If a small business owner decides to rebuild, the process can begin after human health and safety are restored, the electricity is back on, and transportation is up and running. Everyone will want life to return to normal following the destruction, but that may not be possible for every small business. The market may change. Conditions may change, and a business must change to succeed in disaster recovery.[4]

Disaster Planning

In the film Apollo 13, astronauts and engineers went through seemingly endless simulations of what might go wrong on a flight to the moon. The astronauts complained that some of the scenarios were unrealistic and almost impossible to occur. But when a near disaster occurred on Apollo 13, the engineers and astronauts were confronted with a problem that had never been considered; however, because of their prior experience with disaster training, they were able to develop a solution.

Rather than being negative, anticipating what can go wrong can be profoundly positive through either prevention or quickly responding to a crisis. The wise small business owner should appreciate Murphy’s Law (“Anything that can go wrong will go wrong”) and Murphy’s first corollary (“And it will go wrong at the worst possible moment”). The most pragmatic small business owner will also realize that Murphy was an optimist.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency declared 741 natural disasters in the United States for the period 2000 to 2011. Of that number, 66 percent were declared across the following six states: Texas (#1), California, Oklahoma, New York, Florida, and Louisiana (#6). However, every state and territory was represented.[5] Planning for the aftermath of severe storms, flooding (e.g., perhaps snow melts too fast), fire, a hurricane or a tornado, a terrorist attack, or—in some areas—an earthquake is the key to getting back to business with a minimum of disruption. Not all businesses will face the same likelihood of these disasters occurring, but everyone faces the possibility of fire, severe storms, and flooding. Every situation will be unique, with the complexity of issues depending on the particular industry, size, location, and scope of a business.[6] The widespread nature of a the typical disaster means that public services, such as police, fire fighters, and medical assistance, will be unable to reach everyone right away. A business might be going it alone for a while.[7]

According to a recent poll conducted by the National Federation of Independent Business, man-made disasters affect 10 percent of small businesses, and natural disasters have impacted more than 30 percent of all small businesses in the United States.[8] Man-made disasters are disastrous events caused directly and principally by one or more identifiable deliberate or negligent human actions.[9] They include such things as arson, radiation contamination, terrorism, structural collapse due to engineering failures, civil disorder, and industrial hazards.[10] The better prepared a business is, the faster it will be able to recover and resume operations…if that is the decision. Having a disaster plan can mean the difference between being shut down for a few days and going out of business entirely.[11]

A Disaster Planning Success Story

Joe Bogner of Dodge City, Kansas, learned the importance of disaster planning firsthand. He owns Western Beverage, Inc., a beverage distribution company serving twenty-nine counties in western Kansas. In 2002, Western Beverage sustained millions of dollars in fire damage. Yet the company resumed deliveries after just three days. Bogner was named the Kansas City Small Businessperson of the Year for 2006, partially because of his company’s ability to respond to adversity. As his nomination package stated, “Setting up plans of action and following through are Joe’s way of life. He has proven and is continuing to prove that dreams can come true.”[12]

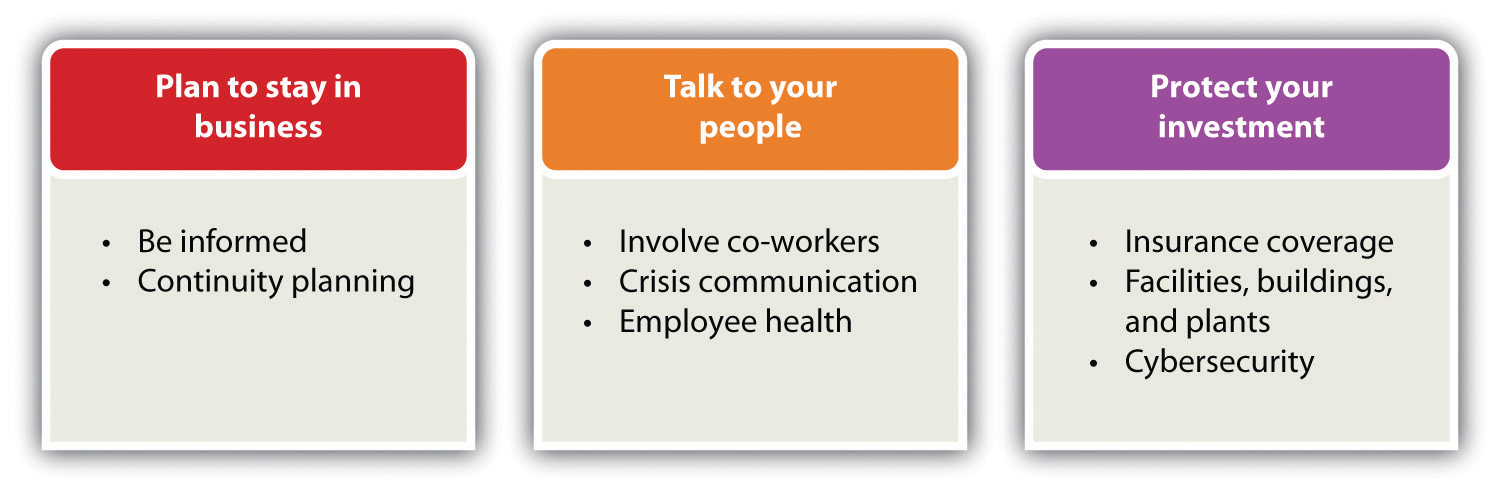

Four key facts about disaster planning must be kept in mind: (1) disasters will occur, (2) an owner must have a plan before the disaster occurs, (3) react with urgency but do not panic, and (4) ride it out.[13] If an owner is committed to having a disaster plan for a business, the plan and process can be structured in a variety of ways. For this section, however, the recommendations on Ready.gov serve as the structure for our discussion. These recommendations reflect the Emergency Preparedness Business Continuity Standard (NFPA 1600) developed by the National Fire Protection Association and endorsed by the American National Standards Institute and the Department of Homeland Security.[14] The recommendations are divided into three areas: plan to stay in business, talk to the people, and protect the investment. The topics discussed here are presented in Figure 6.1 “Disaster Planning”. They have the greatest immediacy for a small business.

A business owner has invested a tremendous amount of time, money, resources, and emotions into building a business, so he or she will want to be able to survive a natural or man-made disaster. This requires taking a proactive approach so that the chances of the business surviving are increased. Unfortunately, nothing can be done to guarantee the survival of a business because there is no way to know what kind of disaster may occur—or when. There is also no way to know what kind of business environment the owner will face after the disaster. There are, however, several things can be done to increase those chances of survival. Resist the temptation to put emergency planning on the back burner.

Be Informed

It is important to look realistically at the types of disasters that might affect a business internally and externally and prepare a risk assessment. Consider the natural disasters that are most common in the areas where the business operates and think about the business’s vulnerability to man-made disasters. Fires are the most common disasters in the United States, and they are extremely destructive to businesses,[16] but an owner may not be aware that a community is very vulnerable to flooding from snow melt or that the proximity to a chemical plant makes a business vulnerable to the results of explosions. This is why it is important to prepare a risk assessment so that the business can plan accordingly.

Make a Continuity Plan

It is said that a business continuity plan is the least expensive insurance any business can have—especially a small business—because it costs virtually nothing to produce.[17] The better the continuity planning is before a disaster, the greater the chances that a business will survive and recover. There are many things that can be done.[18][19] The following is not an exhaustive list:

- Carefully assess how the business functions. Document internal key personnel and backups (i.e., the personnel without whom a business absolutely cannot function). The list should be as large as necessary but as small as possible.

- Identify suppliers, shippers, resources, and other businesses that are interacted with on a daily basis. Document these and other external contacts, such as bankers, attorneys, information technology (IT) consultants, utilities, and municipal and community offices (police, fire, etc.) that may be needed for assistance.

- Identify people who can telecommute. Take steps to ensure that critical staff can telecommute if necessary.

- Plan for payroll continuity.

- Document critical equipment. Personal computers, fax machines, special printers and scanners, and software are critical to most businesses. An accurate inventory will help a business restore critical equipment.

- Make sure that all data and critical documents are protected. Critical documents include articles of incorporation and other legal papers, utility bills, banking information, and human resources documents; all these will be required to start over again. The Small Business Administration (SBA) recommends that vital business records—information stored on paper and computer—should be copied and saved at an offsite location at least fifty miles away from the main business site.[20] Companies such as Carbonite can store records “on the cloud.”

- Identify a contingency location where business can be conducted while the primary office is unavailable. Many hotels have well-equipped business facilities that can be used, but remember that other businesses may need to do the same thing. It is good to have a contingency plan for a contingency location.

- Put all the information together. The continuity plan is an important document, a copy of which should be given to all key personnel. Do not distribute the plan to people who do not need to have it. The plan will contain sensitive and secure information that could be used by a disgruntled employee for inappropriate purposes.

- Plan to change the plan. There will always be events that could not have been factored into the plan. For example, the contingency site is damaged beyond use or the business’s bank is in an area that will be without power for days. Situations such as these will require immediate changes to the plan.

- Review and revise the plan.

Talk to People

Without good communication, the internal and external structure of a business—and its daily operations—will face challenges that may ultimately lead to its downfall.[21] Strong communication skills are, therefore, a vital part of business success. When first starting out, the owner will need good communication skills to attract and keep new customers. As the business grows and new employees are required, these skills will be needed to hire, motivate, and retain good staff.[22] It is for this reason that the employees of a business should play a central role in creating a disaster plan.

Involve Coworkers

Providing for the well-being of all employees is one of the best ways to ensure that a business will recover from a disaster. A business must be able to communicate with them before, during, and after a disaster. There are several recommendations for doing this, including the following:[23]

- Employees from all levels in the organization should be involved.

- Internal communications tools, such as newsletters and intranets, should be used to communicate emergency plans and procedures.

- Set up procedures to warn people, being sure to plan how to warn employees who are hearing impaired, are otherwise disabled, or do not speak English.

- Encourage employees to find an alternate way of getting to and from work in case their usual way of transportation is interrupted.

- Keep a record of employee emergency contact information with other important documents.

Write a Crisis Communication Plan

The owner must decide how the business will contact suppliers, creditors, other employees, local authorities, customers, media, and utility companies during and after the disaster. One easy way to do this is to assign key employees to make designated contacts. Provide a list of these key employees and contacts to each affected employee and keep a copy with other protected contacts. Each key employee should also keep a copy of the list at home. In addition,[24] do the following:

- Make sure that top executives have all the relevant information needed to protect employees, customers, vendors, and nearby facilities.

- Update customers on whether and when products will be received and services rendered.

- Let public officials know what the business is prepared to do to help in the recovery effort.

- Let public officials know whether the business will need emergency assistance to conduct essential business activity.

Support Employee Health—and the Owner’s Health

Disasters often result in business disorientation and environmental detachment, with the psychological trauma of key decision makers leading to company inflexibility (perhaps inability) to deal with the change required to move forward.[25] If the owner or other key personnel experience post traumatic stress disorder, it can cripple a business’s decision-making ability.

No matter the disaster, there will be psychological effects (e.g., fear, stress, depression, anxiety, and difficulty in making decisions) as well as—depending on the nature of the disaster—physical effects such as injuries, burns, exposure to toxins, and prolonged pain.[26] As a result, the owner and the employees may have special recovery needs. To support those needs, do the following:[27]

- Provide for time at home to care for family needs, if necessary.

- Have an open-door policy that facilitates seeking care when needed.

- Reestablish routines as best as possible.

- Offer special counselors to help people address their fears and anxieties.

- Take care of yourself. Leaders tend to experience increased stress after a disaster. The leader’s own health and recovery are also important to both family and the business as a whole.

Protect the Investment

Last but certainly not least, take steps to protect the business and secure its physical assets. Among the things that can be done, having appropriate insurance coverage; securing facilities, buildings, and plants; and improving cybersecurity are at the top of the list.

Insurance Coverage

Having inadequate insurance coverage can leave a business vulnerable to a major financial loss if it is damaged, destroyed, or simply interrupted for a period of time. Because insurance policies vary, meet with an insurance agent who understands the needs of a particular business.[28]

- Review coverage for things such as physical losses, flood coverage, and business interruption. Normal hazard insurance does not cover floods, so make sure the business has the right insurance.[29] Business interruption insurance protects a business in the event of a natural disaster, a fire, or other extenuating circumstances that affect the ability of a company to conduct business.[30] Small business owners should seriously consider this type of insurance because it can provide enough money to meet overhead and other expenses while out of commission. The premiums for these policies are based on a company’s income.[31]

- Understand what the insurance policy covers and what it does not cover.

- Add coverage as necessary.

- Understand the deductible and make adjustments as appropriate.

- Think about how creditors and employees will be paid.

- Plan how to pay yourself if the business is interrupted.

- Find out what records the insurance provider will require after an emergency and store them in a safe place. It would be a good idea to take pictures of your physical facilities, equipment, buildings, and plant so that insurance claims can be processed quickly. These pictures will also provide a good basis for putting the operation back into working order.

Secure Facilities, Buildings, and Plants

One cannot predict what will happen in the case of a disaster, but there are steps that can be taken in advance to help protect a business’s physical assets, including the following:[32]

- Fire extinguishers and smoke detectors should be installed in appropriate places.

- Building and site maps with critical utility and emergency routes clearly marked should be available in multiple locations—and they should be protected with other important documents.

- Think about whether automatic fire sprinklers, alarm systems, closed circuit television, access control, security guards, or other security measures would make sense.

- Secure the entrance and the exit for people, products, supplies, and anything else that comes into and leaves the business.

- Teach employees to quickly identify suspect packages and letters, for example, packages and letters with misspelled words, no return address, the excessive use of tape, and strange coloration or odor. Have a plan for how such packages and letters are to be handled.

Improve Cybersecurity

Many, perhaps most, small businesses will have data and IT systems that may require specialized expertise. They need to be protected. The industry, size, and scope of a business will determine the complexity of cybersecurity, but even the smallest business can be better prepared.[33] Small businesses are the most vulnerable to cybersecurity breaches because they have the weakest security systems, thereby making them easier online targets.[34]

Video Clip 6.1- Cybersecurity

An overview of cybersecurity.

Video Link 6.1- Chubb Group of Insurance Companies

The Chubb Group of Insurance Companies provides a very good video discussion of cybersecurity.

Every computer can be vulnerable to attack. The consequences can range from simple inconvenience to financial catastrophe.[35] There are several things that can be done to protect a business, its customers, and its vendors, including the following:[36][37][38]

- Explore cybersecurity liability insurance. This coverage is available at reasonable rates to protect against credit card identity theft, with limits up to $5 million. This insurance will cover the loss of digital assets plus expenses for public relations, damages, and service interruption. It will also protect customers. The notification of customers whose credit was compromised is included plus any legal costs and a year of credit monitoring for each individual affected. Although other cybersecurity insurance policies can cover data loss, applicants must break down loss estimates on an hourly basis because most breaches are resolved in hours, not days. This is not an easy thing to do.

- Use antivirus software and keep it up to date. If an owner is not already doing this, he or she should probably have a mental examination.

- Do not open e-mail from unknown sources. Always be suspicious of unexpected e-mails that include attachments, whether or not they are from a known source. When in doubt, delete the file and the attachment—and then empty the computer’s deleted items file. This should be a procedure that all employees know about and follow. The owner must do it as well.

- Use hard-to-guess passwords. An application for cyberinsurance requires, among other things, answering the following question: “Are passwords required to be at least seven characters in length, alphanumeric, and free of consecutive characters?” (Check yes or no.) Whether or not a business plans to apply for cyberinsurance, instituting this kind of password policy is well worth consideration.

Key Takeaways

- Small- to medium-sized businesses are the most vulnerable in the event of a disaster.

- Some estimates claim that over 60 percent of small businesses that experience a major disaster close by the end of the second year.

- Planning for disaster recovery makes great sense for protecting a business.

- Every state and territory has experienced disasters. Planning for the aftermath is the key to getting back to business with a minimum of disruption. However, every situation will be unique.

- Man-made disasters affect 10 percent of small businesses, while natural disasters have impacted more than 30 percent of all small businesses in the United States.

- A man-made disaster is a disastrous event caused directly and principally by one or more identifiable deliberate or negligent human actions—for example, arson, terrorism, and structural collapse.

- The better prepared a business is, the faster it will recover from a disaster and resume operations. Having a disaster plan can mean the difference between being shut down for a few days and going out of business entirely.

- Even the smallest business should have a disaster plan.

- The three main areas that an owner should focus on in a disaster plan are the plan to stay in business, talk to people, and protect the investment.

Exercises

Frank’s BarBeQue just missed being impacted by a tornado that ripped through southwestern Connecticut. Many small businesses were lost, never to reopen, while others sustained major physical and economic damage. Frank’s son, Robert, asked his father about whether he was prepared for something like that. Frank’s response was troubling. Although he kept some important documents in a safety deposit box at the bank, there was little planning or protection. Robert explained the importance of disaster planning, but Frank was overwhelmed by the prospect of the process.

Robert contacted a local university and arranged with its school of business for a team of five students to prepare a disaster plan for Frank’s BarBeQue. He presented the project idea to his father and was relieved that his dad was willing to participate. It was clearly understood that no proprietary or confidential information would be shared with the students.

- Assume that you are the leader of the team. Describe the approach you will take and the recommendations that you will make. It is expected that you will go beyond the information provided in the text. Creativity is strongly encouraged.

Disaster Assistance

Learning Objectives

- Learn about the sources of disaster assistance for the physical and/or economic losses of small business.

Do not assume that all small businesses will qualify for disaster loan assistance or that insurance will cover the costs of all losses. A small business owner may have to depend on other forms of financial assistance—for example, savings, friends, and family.[39] However, if a small business has sustained economic injury after a disaster, it may be eligible for financial assistance from the Small Business Administration (SBA). If a business is located in a declared disaster area, the owner may apply for a long-term, low-interest loan to repair or replace damaged property.[40]

Physical and Economic Injury Disaster Loans

In the case of a physical disaster, a small business owner may apply for a low-interest SBA loan of up to $2 million to repair or replace damaged real estate, equipment, inventory, and fixtures: “The loan may be increased by as much as 20 percent of the total amount of disaster damage to real estate and/or leasehold improvements, as verified by SBA, to protect property against future disasters of the same type. These loans will cover uninsured and or under-insured losses.”[41] It is also possible that small business disaster relief loans may be available at the local, county, regional, or state level.[42]

The SBA can also help small businesses that were not damaged physically but have suffered economically.[43] An Economic Injury Disaster Loan of up to $2 million can be granted to meet necessary financial obligations—expenses the business would have paid if the disaster had not occurred.

The interest rate on both Physical and Economic Injury Disaster Loans will not exceed 4 percent if you do not have credit available elsewhere. Repayment can be up to 30 years, but this will depend on the business’s ability to repay the loan. For businesses that may have credit available elsewhere, the interest rate will not exceed 8 percent. SBA determines whether the applicant has credit available elsewhere.[44]

Disaster Assistance from the Internal Revenue Service

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) provides some disaster assistance and emergency relief for businesses through special tax law provisions, especially when the federal government declares their location to be a major disaster area. The IRS may grant additional time to file returns and pay taxes. While doing disaster planning, check the latest special tax law provisions that may help a business recover financially from the impact of a major disaster.[45] It would also be a good idea to check out what kind of record keeping the IRS requires so that a business will be fully prepared should it be necessary to take advantage of what the IRS offers.

SCORE Business Advice

Disaster recovery will push the limits of a small business…and then some. Locate the closest offices of SCORE (Service Corps of Retired Executives)—a nonprofit association dedicated to educating entrepreneurs and helping small businesses start, grow, and succeed nationwide—and enlist their support. SCORE provides confidential business counseling services at no charge.[46]

Online Disaster Assistance

DisasterAssistance.gov is a one-stop web portal, self-described as access to disaster help and resources, that details over sixty different forms of assistance from seventeen US government agencies where a business owner can apply for SBA loans through online applications, receive referral information on forms of assistance that do not have online applications, or check the progress and status of online applications.[47][48]

Benefits.gov wants to let survivors and disaster relief workers know about the many disaster relief programs that are available. There are questions for a small business owner who has suffered damage because of a natural disaster to answer to find out which government benefits the business may be eligible to receive. The site also provides a link to DisasterAssistance.gov [49]; [50]

Key Takeaways

- Do not assume that a small business will qualify for disaster loan assistance or that insurance will cover the costs of all losses. A small business owner may have to depend on others for financial assistance—for example, friends, family, and savings.

- A small business owner may apply for a low-interest SBA loan of up to $2 million to repair or replace damaged real estate. The interest rate on this loan will not exceed 4 percent if credit is not available elsewhere.

- The SBA also provides financial assistance to small businesses that were not damaged physically but suffered economic losses. The interest rate on this loan will also not exceed 4 percent if the business does not have credit available elsewhere.

- The IRS provides disaster assistance and emergency relief through special tax provisions.

- It would be worthwhile checking out SCORE for assistance.

- Online disaster assistance is available through two website portals: DisasterAssistance.gov and Benefits.gov.

Exercises

- As part of the disaster management plan, Robert has asked the student team to prepare a specific plan for obtaining disaster assistance under the assumption that both physical and economic damages will occur. Review the various options and the material from the previous section in this chapter and then make specific recommendations. It is expected that you will go beyond the information presented in the text.

Escapes: Getting Out of the Business

Learning Objectives

- Identify the situations in which an owner may choose to get out of business.

- Identify and understand the situations that may lead to being forced out of business.

- Understand the resources that can help an owner make a decision.

There are many reasons why an owner might want to walk away from a business; the choice is oftentimes the owner’s. Perhaps the owner wants to sell the business before retirement. Perhaps someone has approached the owner with a terrific offer. Perhaps investors are pressuring the owner for their money. Perhaps no one in the owner’s family wants to take over the business. Perhaps it is no longer fun; the entrepreneurial spirit is gone, and the owner’s passion has changed. It could be that either the owner or the team is not committed to making things work.[51] Perhaps the owner would like to cash out the equity built in the business.[52][53] There are many other reasons as well:

- The owner is spending more time fixing nominal problems, it feels as if he or she is working backward, and no end seems in sight.

- Instead of being the most optimistic person on the team, the owner starts taking a negative view on most of the decisions the team is making about future prospects for growth.

- Continuing with the business may have serious, lasting personal repercussions, such as threatening one’s marriage, familial relationships, or health. The potential risk is no longer worth the reward.

- The owner sees the writing on the wall: no repeat or referral customers, no positive feedback from any source, or no demand for the business’s product or service. Positive feedback can take many forms: word of mouth, referrals, favorable press, favorable posts and reviews on Facebook and Twitter, and plenty of inquiries. If a business owner is not satisfying customers and attracting new ones, why be in business at all?

When Walking Away Is Not the Owner’s Choice

There will also be those times when walking away from a business may not be the owner’s choice.

-

The owner wants no one else to run the business and is unwilling to give up equity. Every small business founder faces the founder’s dilemma—that is, the dilemma between making money and controlling the business.[54] It is tough to do both because they tend to be incompatible goals. Founders often make decisions that conflict with maximizing wealth.[55] If an owner wants to make a lot of money from a business, the owner will need to give up more equity (the money put into the business) to attract investors, which requires relinquishing control as equity is given away; investors may alter the board membership of a business.[56] To retain control of a business, the owner will have to keep more equity, relying on his or her own capital instead of taking money from investors. The result will be less capital to increase a company’s value, but he or she will be able to run the company.[57]

In a recent study of 212 new ventures, it was found that in three years, 50 percent of the founders were no longer the CEO, only 20 percent were still “in the corner office,” and fewer than 25 percent led their company’s initial public offering (IPO). Four out of five found themselves being forced to step down at some point.[58][59] Although specific to new ventures, this information has a clear message for all small business founders/owners: wanting to make a lot of money while still controlling and running the business are not compatible goals. One must decide which goal is most important, understanding that the choice of letting someone else run the business will likely result in being forced to step down…and perhaps out of the business altogether.

- The owner is facing bankruptcy. One study, [60] found that firms with less sophisticated owners or managers with respect to experience and training increases the likelihood of bankruptcy as do a deteriorating market and having less access to capital. There can be other reasons as well—for example, employee theft, fraud, or a consumer liability lawsuit that drains a company’s assets.

- The owner may be the cause. The owner could be killing the company or, at the very least, shooting himself or herself in the foot. There are several ways in which this could happen: [61] (1) micromanaging, which may lead to, for example, employees presenting problems or issues but no solutions, unusually high turnover, and never receiving a project that the owner does not change; (2) spending money in the wrong places—for example, spending money on items not needed, such as a fancier location, hiring more staff than needed, and attending costly trade shows with limited or no return on investment; (3) chasing after every customer instead of focusing on the ideal and regular customers that should be reached; (4) the owner is not on top of the numbers, perhaps because he or she is not financially minded and has not taken the time to become financially minded or hire someone as the finance person; and (5) the owner is not a people person, perhaps being a “my way or the highway” kind of person who invests no emotion or warmth when dealing with employees and colleagues, or is an egomaniac.

- The owner is seriously ill. Being ill will raise doubts about a company’s future, and new businesses are the most vulnerable.[62] If there is no one in the owner’s family who is interested in or willing to take over the business, this can add additional stress to the situation.

- The industry dies or implodes. Sometimes the demand for a service or a product just dies—for example, web-consulting companies during the dot-com bust in 2000 and 2001.[63] Henrybuilt Corporation, a Seattle firm that specialized in designing kitchens from $30,000 to $100,000, saw its sales come to a standstill in 2008. Everyone was cancelling projects. The company modified its product and was able to survive.[64]

Resources to Help Make a Decision

The decision to walk away from a business—whether that decision is voluntary or forced—is not an easy one to make. Consult with an appropriate mix of individuals; a partner or partners if applicable, your spouse, your family, an attorney, an accountant, and perhaps someone from SCORE. Each individual can offer a different perspective and different counsel. Ultimately, however, the decision is the owner’s.

One thing is for certain. Whether the escape is voluntary or forced, there should be an exit strategy.

Key Takeaways

- Escaping from a business is the owner’s choice when, for example, he or she wants to sell the business before retirement, someone has approached the owner with a terrific offer, investors are pressuring the owner for their money, no family member wants to take over the business, or it is not fun anymore.

- An escape may be forced when, for example, an owner wants no one else to run the business and is unwilling to give up equity or is facing bankruptcy or is seriously ill.

- The owner should consult with a mix of resources before making a decision.

Exercises

- You are the twenty-eight-year-old founder of a very successful, five-year-old software company. For the last three years, sales have doubled in each year. Last year’s sales were $75 million. A major high-tech firm wants to buy your company. They will offer cash and will sweeten the offer by allowing you the option of being CEO for at least two years. How much would the firm have to offer you to take this deal? How would you know if it was a fair offer? Would you exercise the option to act as CEO for the two years? If you took the offer, what would be your life plans?

Exit Strategies

Learning Objectives

- Understand the importance of an exit strategy.

- Explain the exit strategies that a small business can consider.

The most emotional topic a small business owner will face while building a business—and the hardest decision to make—is when and how to exit the business. This very personal decision should be considered while building the business because this decision will impact many other decisions made along the way.[65] Ultimately, however, an exit strategy must be developed whether or not it is considered along the way. The strategy should be developed early in the business, and it should be reviewed and changed periodically because conditions change. Unfortunately, many small business owners have no exit strategy. This will make an already very emotional decision and process even more difficult.

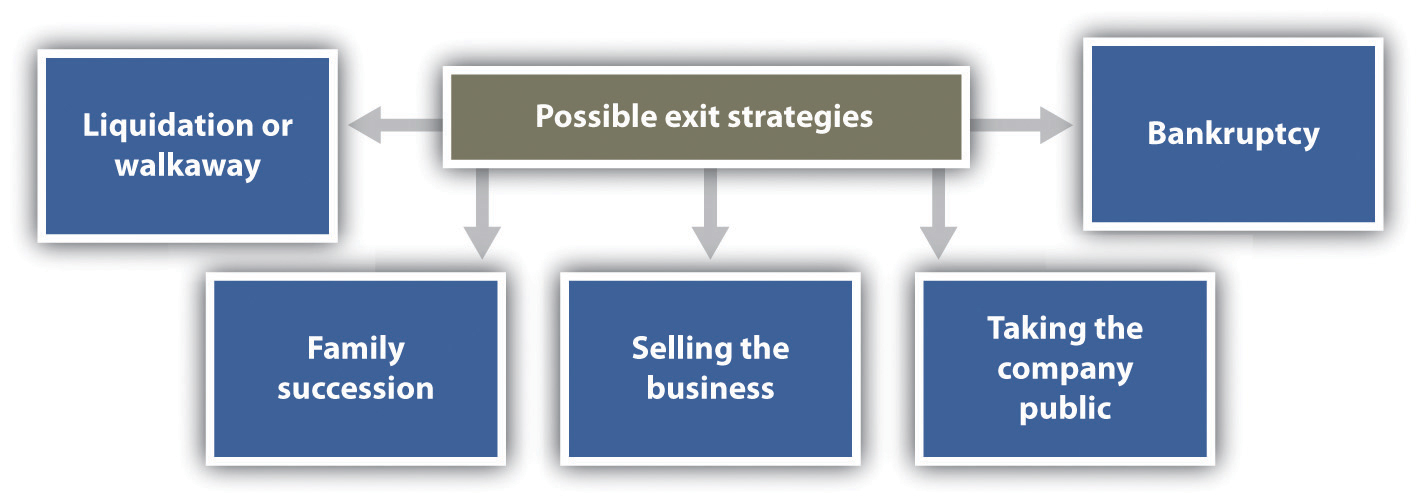

There are many exit strategies that a small business owner can consider. Liquidation or walk away, family succession, selling the business, bankruptcy, and taking the company public are discussed here. Selecting an exit strategy is important because the way in which an owner exits can affect the following:[66]

- The value that the owner and/or shareholders (if any) can realize from a business

- Whether a cash deal, deferred payments, or staged payments are received

- The future success of the business and its products or services (unless one is closing the business)

- Whether the owner wants to retain any involvement in or control of the business

- Tax liabilities

Figure 6.4 Possible Exit Strategies

The best exit strategy (see Figure 6.4 “Possible Exit Strategies”) is the one that is the best match to a small business and the owner’s personal and professional goals. The owner must first decide what he or she wants to walk away with—for example, money, management control, or intellectual property. If interested only in money, selling the business on the open market or to another business may be the best choice. If, on the other hand, one’s legacy and seeing the small business continue are important, family succession or selling the business to the employees might be a better solution.[67]

Liquidation or Walkaway

There are times when a small business owner may decide that enough is enough, so he or she simply calls it quits, closes the business doors, and calls it a day.[68] This happens all the time, to hundreds of businesses every day—for example, a small shop, a restaurant, a small construction company, a shoe store, a gift shop, a consignment shop, a nail salon, a bakery, or a video store.[69] This closing of the business involves liquidation, the selling of all assets. If all debts are paid, it can also be referred to as a walkaway.

To make any money with the liquidation exit strategy, a business must have valuable assets to sell—for example, land or expensive equipment. The name of the business may have some value, so it could be purchased by someone for pennies on the dollar and restarted with different owners. There is also a possibility that there may be a substantial amount of goodwill or even badwill if a business has been around for a long time. Goodwill is an intangible asset that reflects the value of intangible assets, such as a strong brand name, good customer relationships, good employee relationships, patents, intellectual property, size and quality of the customer list, and market penetration.[70] However, if a business is simply closed, the value of the goodwill will drop, and the selling price will be lower than it would have been prior to the business being closed.[71]

Badwill is the negative effect felt by a company when it is found out that a company has done something not in accord with good business practices. Although badwill is typically not expressed in a dollar amount, it can result in such things as decreased revenue; the loss of clients, customers, and suppliers; the loss of market share; the loss of credit; federal or state indictments for crimes committed, and censure by the community.[72] For the small business owner who wants to close under these circumstances, there will be nothing much to sell but tangible assets because the business will have very little, if any, market value.

In all instances of liquidation, the proceeds from the sale of assets must first be used to repay creditors. The remaining money is divided among the shareholders (if any), the partners (if any), and the owner.[73] In an ideal walkaway situation, the following occurs:[74]

- All bills are paid off (or scheduled).

- All taxes are paid, and the various levels of government are informed of the closure.

- Contracts, leases, and the like are fulfilled or formally terminated.

- Employees are let go to find other jobs.

- Assets or inventory is depleted.

- No lawsuits are consuming money and time.

- Customers are placed so that they get needed goods or services.

- If needed, insurance is continued to cover unexpected claims after the firm closes.

The walkaway is the cleanest and best way to exit, but it is not always possible for all businesses that decide to close their doors. There will, of course, always be those instances in which the owner closes the business and takes off, leaving a mess behind.

Any small business owner thinking about liquidation should consider the pros and cons, which are as follows:[75][76]

-

Pros

- It is easy and natural. Everything comes to an end.

- No negotiations are involved.

- There are no worries about the transfer of control.

-

Cons

- Get real! It is a waste. At most, the owner will get the market value of the company’s assets.

- Things such as client lists, the owner’s reputation, and business relationships may be very valuable. Liquidation destroys them without an opportunity to recover their value.

- Other shareholders, if any, may be less than thrilled about how much is left on the table.

- If a company’s brand has any value, there is a loyal or sizeable customer base, or there is a stable core of employees, an owner would be significantly better off selling the company.

Family Succession

Many small business owners dream of passing the business to a family member. Keeping the business in the family allows the owner’s legacy to live on, which is clearly an attractive option. Family succession as an exit strategy also allows the owner an opportunity to groom the successor; the owner might even retain some influence and involvement in the business if desired.[77] However, given that very few family firms survive beyond the first generation and even fewer survive into the third generation. [78][79][80] Succession is the most critical issue facing family firms.[81] Succession is the transference of leadership from one generation to the next to ensure continuity of family ownership of the business.[82]

A sudden decision to hand over the business to a family member is unwise. The owner will be burdened with problems that will likely lead to business failure. Succession in family firms is a multistage, complex process that should begin even before the heirs enter the business, and effects extend beyond the point in time when they are named as successors. Many factors are involved, and the succession should evolve over a long period of time.[83][84] Further, because succession is usually followed by changes in the organization, particularly the change in the top position, it is thought to be an indicator of the future of the business. The better prepared and committed the successor is, the greater the likelihood of a successful succession process and business.[85] The quality of interpersonal relationships, successors’ expectations, and the role of the predecessor are also relevant to success.[86]

The ideal is for the family business to have engaged in formal succession planning: planning for the family business to be transferred to a family member or members. The failure to plan for succession is seen as a fundamental human resource problem as well as the primary cause for the poor survival rate of family businesses.[87] Unfortunately, a very small percentage of family businesses plan appropriately for succession, and those that do frequently have mental, not written, plans.[88]

Video Clip 6.2- Family Business Succession

Tarzan Zerbini Circus

Bankruptcy

Feeling the need to file for bankruptcy is a tough pill for any small business owner to swallow. Bankruptcy is an extreme form of business termination that uses a legal method for closing a business and paying off creditors when the business is failing and the debts are substantially greater than the assets.[89] Because bankruptcy is a complicated legal process, it is important to get an attorney involved as soon as possible. There may be options other than bankruptcy, and consulting with an attorney will help. The owner must understand how bankruptcy works and the options that are available. It is also good to know that not all bankruptcies are voluntary; creditors can petition the court for a business to declare bankruptcy.[90]

Chapter 7 small business bankruptcy, more commonly referred to as liquidation, is appropriate when a business is failing, has no future, and has no substantial assets. This form of bankruptcy makes sense only if the owner wants to walk away. It is particularly suited to sole proprietorships and other small businesses in which the business is essentially an extension of its owner’s skills.[91][92] Under Chapter 7 bankruptcy law, a trustee will take a business apart, selling assets to satisfy outstanding debts and discharging debts that cannot be satisfied with the assets that are available.[93][94]

Small business bankruptcy allows an owner to run a business with court oversight. The owner loses control of the firm, but it continues to operate. The owner is protected from creditors in the short term because the court orders an automatic stay that prevents the creditors from seizing your assets. Unfortunately, the outcome is not pleasant. The owner is out as manager, and the creditors end up owning the business. If the owner cannot pay the $75,000+ in legal fees, the judge will probably order liquidation.[95] This form of bankruptcy applies to sole proprietorships, corporations, and partnerships.[96]

The amount that creditors can collect will depend on how a business is structured. If a business is a sole proprietorship, the owner’s personal assets may be used to pay off business debts, depending on the chosen bankruptcy option. If a business is a corporation, a limited liability company, or some form of a partnership, the owner’s personal assets are protected and cannot be used to pay off business debts.[97]

Alternatives to Bankruptcy

Instead of going the bankruptcy route, a small business owner could do the following things: [98] This is also known as a Consumer Proposal within Canada.

- Negotiate debt. This involves trying to reorganize a business’s finances outside a legal proceeding. The owner can work with the creditors to renegotiate the terms of payment and the amount owed to each creditor. If a business is basically profitable but the debt situation is due to an unusual circumstance, such as a lawsuit or a temporary industry slowdown, this could be a successful solution.

- Improve operations. If the owner is in a position to fix the cash problem by fixing the underlying problems in the business, it may not be necessary to declare bankruptcy. An owner should look at cash-flow controls; eliminate unprofitable products, services, and divisions; and restructure into a leaner and meaner organization.

- Turn around and restructure the business. This alternative combines debt negotiation and operational improvement—perhaps the best choice. By doing both things at the same time, an owner will be in an even stronger position to improve the balance sheet, cash flow, and profitability—and avoid insolvency.

Taking a Company Public

An initial public offering (IPO) is a stock offering in which the owner or owners of equity in a formerly private company have their private holdings transferred into issues tradable in public markets, such as the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE).[99] From the initial owners’ perspective, an IPO is often seen as liquidation, but it is also a money event for a company. For this reason, an IPO makes sense only if a small business can benefit from a substantial infusion of cash. [100]

IPOs receive lots of press, even though they are really very rare. In a typical year, there may be 200 IPOs, perhaps even less. Consider the following data:[101][102][103][104]

- 2008: 32 IPOs

- 2009: 63 IPOs

- 2010: 157 IPOs

- 2011: 159 IPOs

Why are the numbers so small? [105] The IPO process is costly, labor intensive, and usually requires an up-front investment of more than $100,000. Detailed reports are required on a business’s financials, staffing, marketing, operations, management, and so forth. Preparing these reports typically costs hundreds of thousands of dollars, sometimes millions, every year. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act alone, a product of the Enron scandal, costs even the smallest companies several hundred thousands of dollars in consulting fees. Lastly, many companies are not valued very highly on the stock market.

When thinking about an IPO, consider the following pros and cons: [106]

-

Pros

- The owner will be on the cover of Newsweek.

- The stock will be worth in the tens—or even hundreds—of millions of dollars.

- Venture capitalists will finally stop bugging the owner as they frantically try to ensure their shares will retain value.

-

Cons

- Only a very few number of small businesses actually have this option available to them because there are so few IPOs in the United States each year.

- A business needs financial and accounting rigor from day one that is way beyond what many small business owners put in place.

- The owner will spend most of his or her time selling the company, not running it.

- Investment bankers take 6 percent off the top, and the transaction costs of an IPO can run into the millions.

Stever Robbins of Entrepreneur paints an amusing but very dismal picture of what is actually involved in an IPO.[107]

You start by spending millions just preparing for the road show, where you grovel to convince investors your stock should be worth as much as possible…Unlike an acquisition, where you craft a good fit with a single suitor, here you are romancing hundreds of Wall Street analysts. If the romance fails, you’ve blown millions. And if you succeed, you end up married to the analysts. You call that a life? Once public, you bow and scrape to the analysts. These earnest 28-year-olds—who haven’t produced anything of value since winning their fifth grade limerick contest—will study your every move, soberly declaring your utter incompetence at running the business you’ve built over decades. It’s one thing to receive this treatment from your loving spouse. It’s quite another to receive it from Smith Barney. We won’t even talk about the need to conform to Sarbanes-Oxley, or the 6 percent underwriting fees you’ll pay to investment bankers, or lockout periods, or how markets can tank your wealth despite having a healthy business, or how IPO-raised funds distort your income statement, or… In short, IPOs are not only rare, they’re a pain in the backside. They make the headlines in the very, very rare cases that they produce 20-year-old billionaires. But when you’re founding [and running] your company, consider them just one of many exit strategies. Realize that there are a lot of ways to skin a cat, and just as many ways to get value out of your company. Think ahead, surely, but do it with sanity and gravitas. And if you find yourself tempted to start looking for more office space in preparation for your IPO in 18 months, call me first. I’ll talk you down until the paramedic arrives.

For some small businesses, although not many, an IPO might make sense—and may even be necessary. For most, however, an IPO is clearly not a viable exit strategy.

Selling the Business

Another possible exit strategy is selling the business. Although the sale of a business is sometimes described as the end of entrepreneurship or as failure or defeat,[108] selling the business can also be a relief and the beginning of the next phase of the owner’s personal and professional life. As in the case of SoBe (highlighted at the beginning of this chapter), the owners sold the business because, among other things, it was becoming something they did not want it to be—and it was no longer fun. Whatever the reason, an owner can sell a business only once, so be sure that it is the right exit strategy. The owner should address the following questions:[109][110]

- Can the business be sold? There are many things that make a business attractive to buyers: a solid history of profitability, a large and loyal base of customers, a good reputation, a competitive advantage (e.g., intellectual property rights, patents, long-term contracts with clients, and exclusive distributorships), opportunities for growth, a desirable location, a skilled workforce, and a loyal workforce. If a business does not have at least some of these things or others of equal value, it will not likely generate much interest in the market.

- Is the owner ready to sell or does the owner need to sell? Selling a business, when it is a choice, requires emotional and financial readiness. The owner must think about what life will be like after the business is sold. What will be a source of income? How will time be spent? Has the owner “sold out” or could more have been done with the business? Does the owner love what he or she is doing? Many small business owners suffer real remorse after handing their businesses over to a new owner. Selling the business because the owner is forced to will engender very different emotional and financial challenges.

- What is the business worth? The owner may have no idea. For example, the owner of a small professional services firm felt the firm was worth more than $1 million. After a lengthy search, however, the owner received less than one-half that amount from the buyer. On the other side of the coin, the owner of an information technology (IT) company planned to sell the company to an employee for $200,000. However, after advertising the business for sale nationwide, the owner sold it for one dollar shy of $1 million.

It is recommended that an owner start planning for a sale at least three to four years in advance. Sometimes, even five years is not long enough. It is very easy to become overly attached to a business, so it will be difficult to see how the business really looks to an outsider.[111] Selling a business is an art and a science. If the asking price is too high, this may signal to potential buyers that the owner is not really interested in selling. Because there are several methods used to value a business, it is a good idea to hire a professional.[112]

There are different ways to sell a business (see Figure 6.5 “Four Ways to Sell a Small Business”). Acquisition, friendly buyout, selling to the employees, and selling on the open market are discussed here. Be aware, however, that if a business is floundering and it is well known that the business is having major problems paying bills, vulture capitalists, might start circling. A vulture capitalist is a venture capitalist who invests in floundering firms in the hope that they will turn around.[113][114] A venture capitalist is an investor who either provides capital to start-up ventures or supports small companies to expand but does not have access to public funding. Venture capitalists typically expect higher returns because they are taking additional risks.[115]

Figure 6.5 Four Ways to Sell a Small Business

Acquisition

When one business buys another business, as in the case of Pepsi buying SoBe, it is called an acquisition. Businesses buy other businesses for all kinds of reasons—for example, as a quick path to expansion or diversification or to get rid of the competition. When Pepsi was considering acquiring SoBe, their first thought was to kill the brand. But the bottlers convinced them otherwise, saying that it was a very strong brand.[116]

Acquisition is one of the most common exit strategies for a small business. One key to success is to target the potential acquirer(s) in advance, position the business accordingly, and convince the acquirer that the small business is worth the asking price.[117] Another way to become the target of an acquisition is to be successful in the marketplace. This happened with SoBe. Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Arizona, and Campbell’s all expressed an interest after SoBe became a national brand. Pepsi ended up being the acquirer in the end.[118]

In an acquisition, the owner negotiates the price—a good thing because public markets value a business relative to its industry, which limits the value of a business. In an acquisition, however, there is no limit on the perceived value of a company. Why? The person making the acquisition decision is rarely the owner of the acquiring company, so there is no problem with the checkbook. It is someone else’s money.

When thinking about an acquisition, consider the following pros and cons:

-

Pros – [119]

- If a business has strategic value to an acquirer, it may pay far more than the business is worth to anyone else.

- If multiple acquirers are in a bidding war, the owner can raise the price “to the stratosphere.”

-

Cons – [120]

- If the owner organizes the business around a specific acquirer, the business may be unattractive to other buyers.

- Acquisitions are messy and often difficult when cultures and systems clash in the merged company. Although not a small business example, the Warner-AOL combination was a failure largely due to a major culture clash.

- Acquisitions are frequently accompanied by noncompete agreements and other strings that, while making the owner rich, can make life unpleasant for a while. Noncompete agreements are enforceable, but their enforcement depends on the applicable facts and circumstances—including which state’s law governs.[121]

Friendly Buyout

A friendly buyout occurs when ownership is transferred to family members, customers, employees, current managers, children, or friends. It is still considered selling the business, but the terms and nature of the transaction are usually very different. No matter who the “friendly” buyer may be, figure on starting to plan early—and engage a professional before, during, and after the sale.[122][123]

When thinking about friendly buyout, consider the following pros and cons:

-

- The owner knows much more about the buyer, and the buyer knows the owner. There is less due diligence required.

- The buyer will most likely preserve what is important about the business.

- If management buys the business, it has a commitment to make it work.

-

- The owner will be less objective about the buyer and more likely to let his or her guard down in negotiations and planning. The owner leaves too much money on the table.

- If the owner sells to a friend, the friend will be less than thrilled when discovering, for example, decades’ worth of unpaid taxes.

- Selling to family can tear a company apart with jealousies and promotions that put emotion ahead of business needs.

Selling to Employees

Selling the business to employees and/or managers is another option to consider. “Arranging an employee buyout can be a win-win situation as they get an established business they know a great deal about already and you get enthusiastic buyers that want to see your business continue to thrive.”[128] The owner can accomplish this process by setting up an employee stock option plan (ESOP). However, because the owner is giving control of the business to the employees, a transition plan is critical to make sure that they are ready to carry on the business after the owner leaves. It is a good idea to hire an ESOP specialist. Keep in mind, though, that only corporations are eligible to form an ESOP. An ESOP is expensive to set up and maintain, so this might not be the best choice.[129]

If an ESOP is not appealing or the business is not eligible to have an ESOP, selling the business could be as simple as having a current employee take it over. The owner could also consider a worker-owned cooperative, in which interested employees become members of a cooperative that buys the business.[130] In the case of Select Machine of Brimfield, Ohio, “[the owners] sold 30 percent of their stock to the co-op in the first of several installments. The co-op took out loans in the amount of $324,000, which were personally guaranteed by the sellers. The loans were paid off out of company profits over three years; subsequent installments have been owner-financed. Today the co-op owns 59 percent of the company’s stock, and sale of an additional 10 percent is now on the table.”[131]

For a worker-owned cooperative to work, the business owner(s) must be totally committed to the sale of the business to the employees. It is a good option if the business is small (fewer than twenty-five employees), profitable, relatively debt free, already has a culture of participatory management, and the owners are willing to stay on throughout the transition.[132]

Selling on the Open Market

Selling a business on the open market is the most popular exit strategy for small businesses.[133] Unfortunately, it has been estimated that 75 percent of US businesses do not sell,[134] so if this is how the owner wants to sell the business, it must be marketed in a way that maximizes its value in the eyes of a potential buyer.

An owner also needs to spread the word. Most savvy business buyers use the Internet to research available businesses for sale, so post the sale notice on the two largest websites:[135] BizBuySell.com, self-described as the “Internet’s Largest Business for Sale Marketplace,” and BizQuest.com, self-described as the “Original Business for Sale Website.”

Key Takeaways

- The most emotional topic an owner will face when building a business—and the hardest decision he or she will probably have to make—is when and how to exit.

- An exit strategy should be planned while running the business. Unfortunately, many small businesses do not have an exit plan.

- There are many exit strategies that a small business owner can consider, including liquidation or walkaway, family succession, selling the business, bankruptcy, and taking a company public.

- The best exit strategy is the one that best matches the small business and the owner’s personal and professional goals.

- Liquidation is the selling of all assets. If all debts are paid, it can also be referred to as a walkaway. Walking away is the cleanest and best way to exit a business.

- Family succession is the transference of leadership from one generation to the next to ensure continuity of family ownership in the business. It is a critical issue in family businesses because few family firms survive beyond the first generation and even fewer survive into the third generation.

- The failure to plan for succession is seen as a basic human resource problem as well as the primary cause for the poor survival rate of family businesses.

- Bankruptcy is an extreme exit strategy that uses a legal method for closing a business and paying off creditors when a business is failing and the debts are substantially greater than the assets.

- Debt negotiations, operational improvements, or business turnaround and restructuring are alternatives to bankruptcy.

- An IPO is a stock offering in which the owner or owners of equity in a business have their private holdings transferred into issues tradable in public markets, such as the NYSE.

- There are several options for selling a business: acquisition, friendly buyout, selling to the employees, and selling in the open market.

- An acquisition is when another business buys a business. In an acquisition, there is no limit on the perceived value of the business.

- A friendly buyout is the transfer of ownership to family members, customers, employees, current managers, children, or friends—but it is still a sale.

- Selling to the employees can be a win-win situation because they get an established business that they know a great deal about already, and the owner gets enthusiastic buyers who want to see a business continue to thrive.

- Selling in the open market is the most popular exit strategy for small businesses.

- It has been estimated that 75 percent of small businesses do not sell, so a business must market in a way that maximizes its value in the eyes of the potential buyer.

Exercises

-

Two executives of a regional food company are regular customers and big fans of Frank’s All-American BarBeQue. They recently learned that Frank has been selling his sauces in local grocery stores and have been a big hit. The executives bought jars of each flavor, took them back to their company, and talked to the people who would decide about adding products to their line. Everyone loved the sauces, and there was definite interest in acquiring the sauce-making side of Frank’s business. It would fill a hole in their product line that they had been looking to fill.

The company contacted Frank about its interest, and Frank—with some urging from his son, Robert—is thinking about it. It would provide Frank with a nice retirement (when he decides to do that), money for his son and daughter, and a legacy. How should Frank proceed?

- Source: Interview with John Bello, cofounder of SoBe, August 23, 2011. ↵

- “Planning Can Cut Disaster Recovery Time, Expense,” US Small Business Administration, accessed February 6, 2012, archive.sba.gov/idc/groups/public/documents/sba_homepage/serv_da_dprep_howtoprep.pdf. ↵

- Darrell Zahorsky, “Disaster Recovery Decision Making for Small Business,” About.com, accessed February 6, 2012, sbinformation.about.com/od/disastermanagement/a/disasterrecover.htm. ↵

- Darrell Zahorsky, “Disaster Recovery Decision Making for Small Business,” About.com, accessed February 6, 2012, sbinformation.about.com/od/disastermanagement/a/disasterrecover.htm. ↵

- “Declared Disasters by Year and State,” Federal Emergency Management Agency, accessed February 6, 2012, www.fema.gov/news/disaster_totals_annual.fema. ↵

- “Planning Can Cut Disaster Recovery Time, Expense,” US Small Business Administration, accessed February 6, 2012, archive.sba.gov/idc/groups/public/documents/sba_homepage/serv_da_dprep_howtoprep.pdf. ↵

- F. John Reh, “Survive the Unthinkable through Crisis Planning,” About.com, accessed February 6, 2012, management.about.com/cs/communication/a/PlaceBlame1000.htm. ↵

- Darrell Zahorsky, “Disaster Recovery Decision Making for Small Business,” About.com, accessed February 6, 2012, sbinformation.about.com/od/disastermanagement/a/disasterrecover.htm. ↵

- “Man-Made Disaster,” BusinessDictionary.com, accessed February 6, 2012, www.businessdictionary.com/definition/man-made-disaster.html. ↵

- “Anthropogenic Hazard,” Wikipedia, accessed February 6, 2012, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_man-made_disasters. ↵

- “Disaster Preparedness: FAQs,” US Small Business Administration, accessed February 6, 2012, sbaonline.sba.gov/services/disasterassistance/disasterpreparedness/serv_da _dprep_howcaniprep.html. ↵

- “Planning Can Cut Disaster Recovery Time, Expense,” US Small Business Administration, accessed February 6, 2012, archive.sba.gov/idc/groups/public/documents/sba_homepage/serv_da_dprep_howtoprep.pdf. ↵

- F. John Reh, “Survive the Unthinkable through Crisis Planning,” About.com, accessed February 6, 2012, management.about.com/cs/communication/a/PlaceBlame1000.htm. ↵

- “Plan For and Protect Your Business,” Ready.gov, accessed February 29, 2012, www.ready.gov/business. ↵

- Source: http://www.ready.gov/business. ↵

- “Fires,” American Red Cross, accessed February 6, 2012, www.sdarc.org/HowWeHelp/DisasterPreparedness/Fire/tabid/81/Default.aspx. ↵

- “How to Create a Business Continuity Plan,” wikiHow, accessed February 6, 2012, www.wikihow.com/Create-a-Business-Continuity-Plan. ↵

- “Plan For and Protect Your Business,” Ready.gov, accessed February 29, 2012, www.ready.gov/business ↵

- “How to Create a Business Continuity Plan,” wikiHow, accessed February 6, 2012, www.wikihow.com/Create-a-Business-Continuity-Plan. ↵

- “Disaster Preparedness: FAQs,” US Small Business Administration, accessed June 1, 2012, http://archive.sba.gov/services/disasterassistance/disasterpreparedness/serv _da_dprep_howcaniprep.html. ↵

- Kristie Lorette, “Importance of Good Communication in Business,” Chron.com, accessed February 6, 2012, smallbusiness.chron.com/importance-good -communication-business-1403.html. ↵

- Leslie Schwab, “Small Business: The Importance of Strong Communication Skills,” Helium, June 20, 2009, accessed February 6, 2012, www.helium.com/items/1486526-strong-communication-skills-are-required-for-success-in-small-business. ↵

- “Plan For and Protect Your Business,” Ready.gov, accessed February 29, 2012, www.ready.gov/business. ↵

- “Plan For and Protect Your Business,” Ready.gov, accessed February 29, 2012, www.ready.gov/business. ↵

- Darrell Zahorsky, “Disaster Recovery Decision Making for Small Business,” About.com, accessed February 6, 2012, sbinformation.about.com/od/disastermanagement/a/disasterrecover.htm. ↵

- John H. Ehrenreich, “Coping with Disasters: A Guidebook to Psychosocial Intervention,” Toolkit Sport for Development, October 2001, accessed February 6, 2012, www.toolkitsportdevelopment.org/html/resources/7B/7BB3B250-3EB8-44C6-AA8E -CC6592C53550/CopingWithDisaster.pdf. ↵

- “Plan For and Protect Your Business,” Ready.gov, accessed February 29, 2012, www.ready.gov/business. ↵

- “Insurance Coverage Review Worksheet,” Ready.gov, accessed February 6, 2012, www.ready.gov/sites/default/files/documents/files/InsuranceReview_Worksheet.pdf. ↵

- “Disaster Preparedness: FAQs,” US Small Business Administration, accessed June 1, 2012, http://archive.sba.gov/services/disasterassistance/disasterpreparedness/serv _da_dprep_howcaniprep.html. ↵

- “Business Interruption Insurance,” Entrepreneur, accessed February 6, 2012, www.entrepreneur.com/encyclopedia/term/82282.html. ↵

- “Business Interruption Insurance,” Entrepreneur, accessed February 6, 2012, www.entrepreneur.com/encyclopedia/term/82282.html. ↵

- “Plan For and Protect Your Business,” Ready.gov, accessed February 29, 2012, www.ready.gov/business. ↵

- “Plan For and Protect Your Business,” Ready.gov, accessed February 29, 2012, www.ready.gov/business. ↵

- “CyberSecurity by Chubb,” Chubb Group of Insurance Companies, accessed February 6, 2012, www.chubb.com/businesses/csi/chubb822.html. ↵

- “Plan For and Protect Your Business,” Ready.gov, accessed February 29, 2012, www.ready.gov/business. ↵

- “Plan For and Protect Your Business,” Ready.gov, accessed February 29, 2012, www.ready.gov/business ↵

- “Cyber Security Liability Insurance,” Wall Street Journal, March 18, 2010, as cited in Robert Hess and Company Insurance Brokers, May 6, 2010, accessed February 6, 2012, robhessco.com/183/cyber-security-liability-insurance/ ↵

- Eric Schwartzel, “Cybersecurity Insurance: Many Companies Continue to Ignore the Issue,” Pittsburg Post-Gazette, June 22, 2010, accessed February 6, 2012, www.post-gazette.com/pg/10173/1067262-96.stm. ↵

- Darrell Zahorsky, “Disaster Recovery Decision Making for Small Business,” About.com, accessed February 6, 2012, sbinformation.about.com/od/disastermanagement/a/disasterrecover.htm. ↵

- “Disaster Assistance For Businesses of All Sizes,” US Small Business Administration, accessed February 28, 2012, archive.sba.gov/idc/groups/public/documents/sba_homepage/serv_da _dprep_factsheethome.pdf. ↵

- “Disaster Assistance For Businesses of All Sizes,” US Small Business Administration, accessed February 28, 2012, archive.sba.gov/idc/groups/public/documents/sba_homepage/serv_da _dprep_factsheethome.pdf. ↵

- See, for example, the small business loans that are available through the Union County Economic Development Corporation (Union, New Jersey) for disaster assistance: scotchplains.patch.com/articles/union-county-makes-small-business-loans -available. ↵

- “Demand Grows for Disaster Loans,” Wall Street Journal, September 7, 2011, accessed February 6, 2012, blogs.wsj.com/in-charge/2011/09/07/demand-grows-for-disaster -loans/?mod=google_news_blog. ↵

- “Disaster Assistance For Businesses of All Sizes,” US Small Business Administration, accessed February 28, 2012, archive.sba.gov/idc/groups/public/documents/sba_homepage/serv_da _dprep_factsheethome.pdf. ↵

- “Disaster Assistance and Emergency Relief for Individuals and Businesses,” Internal Revenue Service, accessed February 6, 2012, www.irs.gov/businesses/small/article/0,,id=156138,00.html. ↵

- “About SCORE,” SCORE, accessed February 6, 2012, www.score.org/about-score. ↵

- “Disaster Assistance and Emergency Relief for Individuals and Businesses,” Internal Revenue Service, accessed February 6, 2012, www.irs.gov/businesses/small/article/0,,id=156138,00.html ↵

- “What Is DisasterAssistance.gov,” DisasterAssistance.gov, accessed February 6, 2012, www.disasterassistance.gov. ↵

- “Disaster Assistance and Emergency Relief for Individuals and Businesses,” Internal Revenue Service, accessed February 6, 2012, www.irs.gov/businesses/small/article/0,,id=156138,00.html ↵

- “Looking for Benefits?,” accessed February 6, 2012, www.benefits.gov. ↵

- “Knowing When to Throw in the Towel,” Fox Business, May 2, 2011, accessed February 6, 2012, smallbusiness.foxbusiness.com/entrepreneurs/2011/05/02/knowing -throw-towel. ↵

- Timothy Faley, “Making Your Exit,” Inc., March 1, 2006, accessed February 6, 2012, www.inc.com/resources/startup/articles/20060301/tfaley.html ↵

- “Knowing When to Throw in the Towel,” Fox Business, May 2, 2011, accessed February 6, 2012, smallbusiness.foxbusiness.com/entrepreneurs/2011/05/02/knowing-throw-towel. ↵

- Dan Bigman, “On the Hunt,” Forbes 185, no. 2 (2009): 56–59 ↵

- Noam Wasserman, “The Founder’s Dilemma,” Harvard Business Review, February 2008, 1–8 ↵