Globalisation

18 Chapter 18: Going Global: Yes or No?

Going Global

Brandon Fisher, the founder of Center Rock Inc., is shown on the left side in the picture. The man to his right is Richard Soppe, the senior drilling application engineer. The number 33 is the number of Chilean miners who were rescued in 2010. Brandon and his company, now at seventy-five employees, are true American heroes.

Center Rock manufactures and distributes a complete line of air drilling tools and products. At its state-of-the-art manufacturing facility in Pennsylvania, they build stock and made-to-order products that are used by leading drilling, oil and gas, foundation, construction, roadway, and mining contractors across North America, Europe, Asia, Russia, and Australia. Fisher entered the global market four years ago as a way to expand the business. He was able to finance the expansion internally, so financing was not an issue.

Center Rock Inc., founded in 1998 by then twenty-six-year-old Brandon Fisher, began as a drilling company. He designed and built his own horizontal drilling rig and, shortly thereafter, began focusing on making Center Rock an air and rock drilling supplier and manufacturer. He recognized the need for a manufacturing company that was reactive to customer needs, with innovative products and 24/7 customer service and support. Working with his high-tech engineering and design team, Fisher created a company different from its competitors with its unique products and service capabilities.

“I love what I do,” says Fisher. “There is always a challenge in this industry to find new ways to drill into the earth, and the challenge feeds the excitement.”[1]

US Small Business in the Global Environment

Learning Objectives

- Understand and appreciate the role of small businesses in the global environment.

- Learn about the global growth opportunities for small businesses.

- Understand the advantages and the disadvantages of a small business going global.

Although small businesses make up a disproportionately large share of the number of companies that export and import, this represents only about 1 percent of the total number of small businesses. Thus many small businesses have yet to compete globally. The opportunities are there. “So much of what America makes is in great demand,” said US Commerce Secretary Gary Locke in an interview, adding further that the growth potential for small companies is outside the United States. Dale Hayes, vice president of US marketing for UPS concurs, observing that the demand for high-quality American products is huge.[2][3] It may be that a small business is already competing globally because foreign-owned companies are competing in our own backyards.[4]

Yet the global marketplace is not relevant to most small businesses. Given that 99 percent of the small businesses in the United States are not operating globally—preferring to grow (if they want to) locally, regionally, and perhaps nationally—it is reasonable to conclude that going global will interest only a few. Those few, however, must undertake careful analyses before jumping into the global arena.

The Small Business Global Presence

It may seem to many that the global market is the domain of the large corporations, but the statistics tell a very different story. Small businesses actually account for close to 97.6 percent of US exporters and 32.8 percent of the value of US exports as well as 97.1 percent of all identified importers and 31.9 percent of the known import value.[5] Consider the following additional facts:[6]

- Small businesses account for 96.4 percent of all manufacturing exporters, which is 17.2 percent of the sector’s $562 billion in exports.

- Nearly 100 percent (99.2 percent) of exporting wholesalers were small businesses, which is 61.1 percent of the sector’s $218 billion in exports.

- Of other companies with exports, 96.9 percent were small businesses. These companies include manufacturing companies of prepackaged software and books, freight forwarders and other transportation service firms, business services, engineering and management services, gas and oil extraction companies, coal mining companies, and communication services, to name a few.

- Small businesses account for 93.6 percent of all manufacturing importers, which is 12.9 percent of the sector’s $602 billion in imports.

- Nearly 100 percent (99.2 percent) of wholesaler importers were small businesses, contributing 56.8 percent of the sector’s $451 billion in imports.

- Small businesses accounted for 94.3 percent of the companies that both exported and imported, accounting for 29 percent of the export value and 27 percent of the import value.

This tells us that small businesses are very active in the global marketplace, and small business success in international markets is extremely important to the welfare of the United States.“[7] Although it is true that small businesses are major users of imported goods, the focus of this chapter is on small business exporting because exporting can be an effective way to diversify the customer base, manage market fluctuations, grow, and become more competitive.[8]

Small businesses are limited in the products and the services that they export. Small business exports are concentrated in four main product categories: computers and electronic products, chemicals, machinery, and transportation equipment. However, the leading product categories in terms of market share were wood products, apparel and accessories, tobacco products, beverages, and leather products.[9]

Although the United States is one of the world’s largest participants in global services trade, very little information exists with respect to services exports by small businesses. What is known is that it is increasingly common for most US services firms to establish a foreign affiliate —a branch or a subsidiary of the parent company established outside the national boundaries of the parent company’s home market—because most services are better supplied in close proximity to the principal or final customers.[10] Additionally, in some business sectors, foreign regulations may restrict the delivery of some services to affiliates only. For example, to comply with domestic solvency requirements, some countries require that personal lines of insurance be carried out only by affiliates. Another example is the protection of intellectual property rights. This is often accomplished through the services of affiliates, thus intellectual property is kept in-house.[11]

What is particularly interesting is that most of the service exporting occurs in businesses with 0–19 employees, with the least service exporting done by small businesses with 300–499 employees. This may be the exact opposite of what you would expect.

The Advantages of Going Global

The flexibility of a smaller company may make it possible to meet the demands of global markets and redefine a company’s programs more quickly than might occur in the larger multinational corporation. [12] A multinational corporation is a company that operates on a worldwide scale without ties to any specific nation or region; it is organized under the laws of its own country.[13] This flexibility of the smaller company is particularly true of the micromultinationals, a relatively new category of tiny companies that operate globally, having a presence and people in multiple countries. [14][15]

These micromultinationals outsource virtually everything to specialists all over the world and sell to people all over the world through the Internet.[16] The Internet is inexpensive technology, and the services designed to help small businesses make it possible for the small company to operate across borders with the same effectiveness and efficiencies as large businesses.[17]

Micromultinationals

Generation Alliance is a branding and design firm that provides services to clients all over the world. They have core employees in Australia and specialist contractors in New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Germany, Switzerland, Jamaica, Dubai, and Singapore. One of their more interesting projects was to rebrand the country of Botswana for the global market.[18]

Worketc operates in the large and competitive business software market. Their focus is small businesses, selling web-based customer relationship management (CRM), project management, billing, shared calendars, help desk, and document management software. The company is headquartered in Sydney, Australia, and it claims happy customers in sixteen countries. The United States accounts for 86 percent of its customers.[19][20]

There are many reasons why small businesses should consider going global:[21][22][23][24]

- A small business that thinks and sells only domestically may be reaching only a small share of its potential customers because 95 percent of the world’s consumers live outside the United States.

- Exporting enables companies to diversify their portfolios and weather changes in the domestic economy. This stabilizes seasonal and cyclical market fluctuations.

- Exporting helps small businesses grow and become more competitive in all their markets, which reduces the dependence on existing markets.

- Exporting increases sales and profits, also extending the sales potential of existing products. Research has shown that exporting can expand total sales 0.6 percent to 1.3 percent faster than would otherwise be the case.

- Exporting companies are able to sell excess production capacity.

- Exporting companies are nearly 8.5 percent less likely to go out of business.

- There are higher worker earnings as well, which contributes to the betterment of the community.

According to the US Small Business Administration (SBA),[25] US exporting businesses experience faster annual employment growth by 2 to 4 percentage points over their nonexporting counterparts. Workers employed in exporting companies have better paying jobs and better opportunities for advancement. Research has estimated that blue-collar worker earnings in firms that export are 13 percent higher than those in nonexporting plants, 23 percent higher when comparing large plants, and 9 percent higher when comparing small plants. White-collar employees also benefit from higher salaries, 18 percent more than their nonexporting counterparts. Less skilled workers also earn more at companies that export. Lastly, the benefits that all workers receive at exporting plants are 37 percent higher and include improved medical insurance and paid leave.

Video Link 18.1 Why Export?

Why small businesses should consider entering the global marketplace.

The Disadvantages of Going Global

There is no question that the benefits of going global are considerable. However, disadvantages or barriers must also be considered. For example, a small business will incur additional costs, such as modifying its product or its packaging (perhaps even changing the name of its product so that it does not convey negative meanings outside the United States), developing new promotional materials, administrative costs (such as hiring staff to launch the export expansion and dedicating personnel for traveling), traveling to foreign locations (very important), and shipping.[26][27] It may also be necessary for the owner to subordinate short-term profits to long-term gains, wait longer for payments, apply for additional financing, and obtain special export licenses.[28] There will be differences in consumer needs, wants, and usage patterns for products; differences in consumer response to the elements of the marketing mix and differences in the legal environment may conflict with those of the United States.[29] Then, of course, there are cultural and language issues along with the all-too-familiar fear of the unknown. [30] A recent survey of exporting and nonexporting members of the National Small Business Association (NSBA) and the Small Business Exporters Association (SBEA) reported the following main barriers to small businesses selling their goods and/or services to foreign customers:[31]

- I do not have goods and/or services that are exportable: 49 percent.

- I do not know much about it and am not sure where to start: 38 percent.

- I would worry too much about getting paid: 29 percent.

- It is too costly: 27 percent.

- It would take too much time away from my regular, domestic sales: 17 percent.

- I cannot obtain financing to offer products or services to foreign customers: 7 percent.

Three things were identified as the single largest challenge: worrying about getting paid (26 percent), feeling that exporting is confusing and difficult to do (24 percent), and having limited goods and/or services that are exportable (18 percent).

Richard Ginsburg in the SBA’s Office of International Trade has commented that most US small businesses simply do not understand the value of taking their business global, further noting that “the number-one barrier to trade is the psychological acceptance that global business is necessary.[32]

Small businesses also face some resource constraints that reduce their ability to export. For example, small businesses are more likely than larger firms to face scarcities of financial and human resources that limit their ability to take advantage of global opportunities. Limited personnel, the inability to meet quality standards, the lack of financial backing, and insufficient knowledge of foreign markets are important constraints affecting the ability of small businesses to export.[33] Fortunately, being proactive, innovative, and willing to take risks have helped small businesses overcome export impediments and improve export performance.[34]

The disadvantages of going global may warrant a go-slow approach, but they should not be viewed as knockout factors. If a business’s financial situation is weak, the timing may not be right for becoming an exporter…but perhaps exporting makes sense in the future. In any case, very careful thinking should precede the decision to export.

2010 Winner of the Growth through Global Trade Award

Source: SteelMaster Buildings. Reprinted with permission.

The UPS Growth through Global Trade Award recognizes businesses with fewer than five hundred employees that are excelling in international trade. The inaugural winner was SteelMaster Buildings LLC, in Virginia Beach, Virginia, a manufacturer, designer, and supplier. The UPS award was followed up by two other national awards and four regional awards related to SteelMaster’s increases in global trade plus a mention in a September 2010 speech by the former US Secretary of Commerce, Gary Locke, at a trade conference. The company earned first place in the 2011 Export Video Contest cosponsored by the SBA and VISA.

Video Link 18.1 Starting an Import/Export Business

How to start an Import/Export business.

SteelMaster employs fifty people, excluding distributors. It exports to more than forty countries and has distributorship relationships in more than fifty international markets (e.g., South Korea, Romania, Mexico, Angola, Chile, Peru, Slovakia, South Sudan, and Australia). This distributor network has provided an important source of market differentiation. Since the company began exporting in 2006, in response to the very competitive and saturated US market, the company’s revenue has quadrupled, and exporting now represents over 20 percent of its total revenue. In addition,

- The SteelMaster website is user-friendly and offers a bilingual choice for Spanish-speaking viewers. Live chat is also available. In addition, various parts of the website have been translated to other languages (i.e., Korean, French, Romanian, Portuguese, and Arabic) to serve the company’s international customers in their own languages.

- SteelMaster buildings are environmentally friendly and can be recycled. Green buildings are offered that protect against nonuniform weathering and reduce energy loads on buildings due to a long-term, bright service that helps heat reflectivity.

- SteelMaster’s Galvalume Plus coated steel has been approved by the ENERGY STAR program for both low-slope and high-slope applications.

- The SteelMaster product can be easily used in the wake of natural disasters, such as earthquakes, flooding, or hurricanes. The company has participated in humanitarian relief efforts, specifically in Haiti.[35][36][37][38] The company stands ready to provide safe and reliable construction solutions to people in need around the world.

Key Takeaways

- Small businesses make up a disproportionately large share of the number of companies that export and import. However, this is only about 1 percent of the total number of small businesses.

- The growth potential for small companies outside the United States is huge because of the demand for high-quality American products.

- Small businesses account for close to 98 percent of US exporters and 33 percent of the value of US exports.

- Small business success in international trade is extremely important to the welfare of the United States.

- There are many advantages and disadvantages of a small business going global. These must be analyzed very carefully before deciding to enter the global marketplace.

- A recent survey of small business owners revealed that the number one barrier to exporting was the feeling that their businesses did not have exportable goods and/or services. The number one challenge was worrying about getting paid.

Exercises

- Go to www.trade.gov/mas/ian/statereports. Select your state and prepare a profile of small business exporting. Review additional sites as well, for example, websites sponsored by your state’s commerce and/or economic development departments. When looking at government sites, you may see the term small- and medium-sized businesses or something similar. They are simply referring to businesses with fewer than five hundred employees. This is the small business group for your purposes.

What You Should Know Before Going Global

Learning Objectives

- Learn about the different ways that a business can export.

- Understand the importance of an industry analysis.

- Understand that it is important to carefully assess a business.

- Learn about the marketing decisions that must be made.

- Learn about the kinds of legal and political issues that will affect the exporting activities of a business.

- Understand why the currency exchange rate is important to determining price.

- Learn about the different sources of financing.

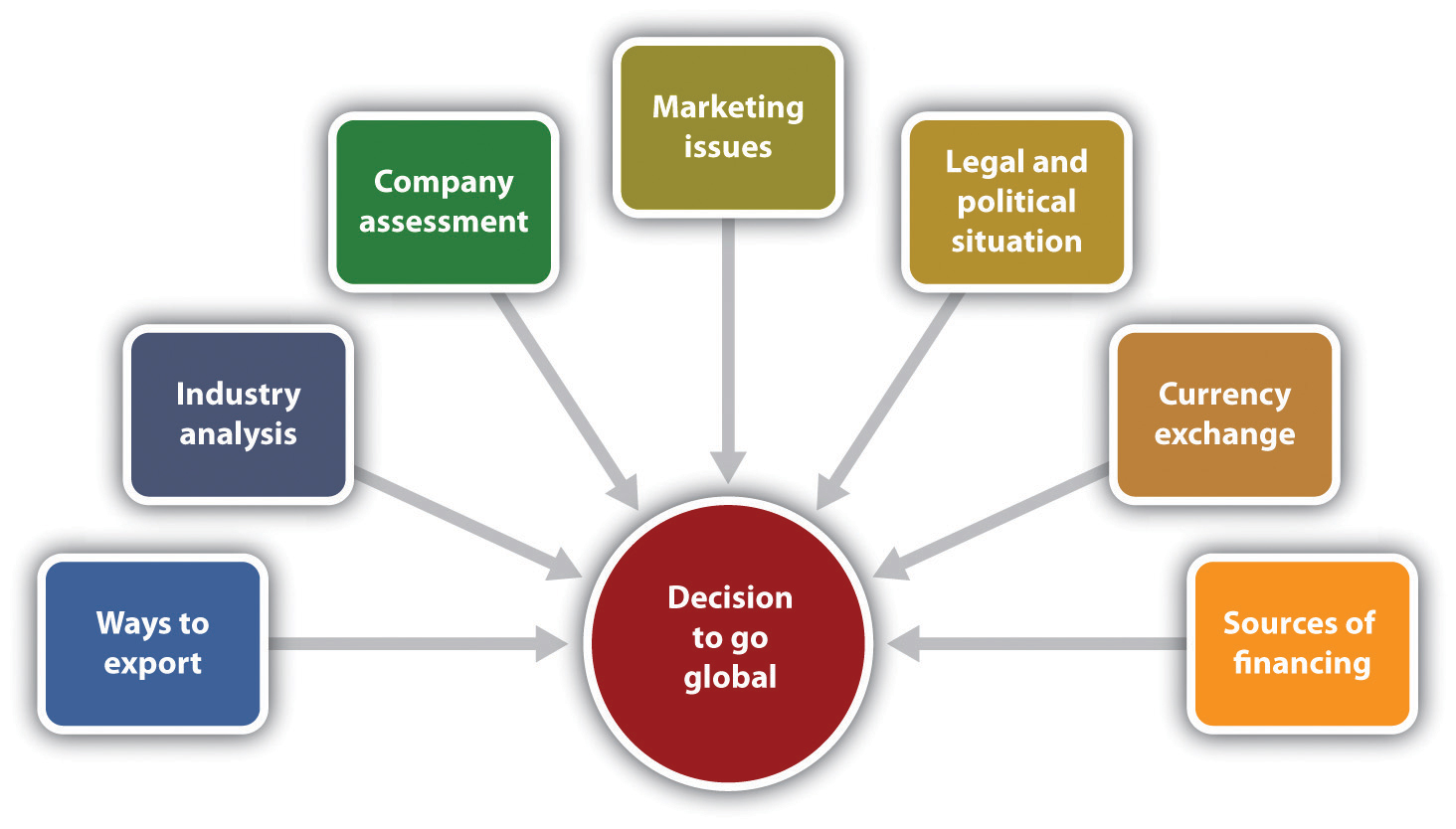

Although expanding into global markets offers many important benefits, not the least of which is increased profits, it will also introduce new complexities into the operations of a small business. There are several key decisions (see Figure 18.1 "Factors Affecting the Decision to Go Global") that will need to be made, including the following:[39]

- Determine which foreign market(s) to enter.

- Analyze the expenditures required to enter a new market and determine the source(s) of financing.

- Determine the best way to organize the overseas operation in concert with the US organization.

- Determine the extent to which, if any, the marketing mix will need to be adapted to the needs of the foreign market(s).

- Figure out the best way for the business to get paid.

These decisions, and others, will be based on an assessment of the ways to export, an analysis of the industry and the business, marketing and cultural factors, legal and political conditions, currency exchange issues, and sources of financing.

Video Link 18.2 A Family Business Goes Global

A small business specializing in leather-care products gets a lesson in expanding beyond its old fashioned clientele.

Figure 18.1 Factors Affecting the Decision to Go Global

Ways to Export

Small businesses can choose from two basic ways to export: directly or indirectly.[40] There are advantages and disadvantages of each that should be understood before making a choice.

Direct Exporting

In direct exporting, a small business exports directly to a customer who is interested in buying a particular product. The small business owner makes all the arrangements for shipping and distributing the product overseas, is responsible for the marketing research, and collects payment. This approach gives the owner greater control over the entire transaction and entitles him or her to higher profits—although these higher profits are accompanied by the need to invest significantly more resources and efforts (see Table 18.1 "Advantages and Disadvantages of Direct Exporting"). It also requires a significantly changed internal organizational structure, which entails more risk.[41][42][43]

Table 18.1 Advantages and Disadvantages of Direct Exporting

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Potential profits are greater because intermediaries are eliminated. | It takes more time, energy, and money than an owner may be able to afford. |

| The owner has a greater degree of control over all aspects of the transaction. | It requires more “people power” to cultivate a customer base. |

| The owner knows customers, and the customers know the owner. Customers feel more secure in doing business directly with the owner. | Servicing the business will demand more responsibility from every level in the organization. The owner is held accountable for whatever happens. There is no buffer zone. |

| Business trips are much more efficient and effective because an owner can meet directly with the customer responsible for selling the product. | The owner may not be able to respond to customer communications as quickly as a local agent can. |

| The owner knows whom to contact if something is not working. The owner gets slightly better protection for trademarks, patents, and copyrights. | The owner must handle all the logistics of the transaction. If it is a technological product, the owner must be prepared to respond to technical questions and provide on-site start-up training and ongoing support services. |

| The owner is presented as fully committed and engaged in the export process and develops a better understanding of the marketplace. As a business develops in the foreign market, the owner has greater flexibility to improve or redirect marketing efforts. |

Source: [44]

Indirect Exporting

Indirect exporting involves entering “into an agreement with an agent, distributor, or a traditional exporting house for the purpose of selling (or marketing and selling) the products in the target market.”[45] Many small businesses choose this option, at least at the outset. It is the simplest approach, particularly when a business does not have the necessary human and financial resources to promote products in foreign markets in any other way (see Table 18.2 "Advantages and Disadvantages of Indirect Exporting").[46][47] The easiest way to export indirectly is to sell to an intermediary in the United States because the business will normally not be responsible for collecting payment from the overseas customer or coordinating the shipping logistics.[48]

Table 18.2 Advantages and Disadvantages of Indirect Exporting

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Does not require a lot of organizational effort or staff workers. | Not all types of goods lend themselves to indirect exporting (e.g., technically complex goods and services). |

| The producer of the goods is subject to only small dangers and risk (e.g., a short-term drop in the exchange rate). | The profits of a business will be lower, and control over foreign sales is lost. |

| It is an almost risk-free way to begin. It demands minimal involvement in the export process. It allows the owner to continue to concentrate on its domestic business. | A business very rarely knows who its customers are, thus losing the opportunity to tailor its offerings to their evolving needs. |

| The business has limited liability for product marketing problems. There is always someone else at which to point the finger. | When an owner visits, he or she is a step removed from the actual transaction and feels out of the loop. |

| The owner learns on the fly about international marketing. Depending on the type of intermediary with which the owner is dealing, the owner does not have to be concerned with shipment and other logistics. | The intermediary might be offering products similar to a particular business’s products, including directly competitive products, to the same customers instead of providing exclusive representation. |

| A business can field-test its products for export potential. In some instances, the local agent can field technical questions and provide necessary product support. | The long-term outlook and goals for an export program can change rapidly, and if a business has put its product in someone else’s hands, it is hard to redirect efforts accordingly. |

Industry Analysis

Before jumping into the global pond, it is a good idea to identify where an industry currently is and then look at the trends and directions that are predicted over the next three years. This will be true whether a business is only on the ground, only online, or both brick and click.

A business should try to determine how competitive an industry is in the global market.[51] Try to get as good a picture of the market as possible because the better informed a business is, the better its chances of a successful global entry. Learn a product’s potential in a given market, where the best prospects for success seem to be, and common business practices.[52]

A small business owner may be reticent about conducting market research before going global, particularly if domestic research efforts have been limited or nonexistent. However, the global market is a very different animal compared to the domestic market. It is even more important to conduct thorough market research to help identify possible risks in advance so that the appropriate steps can be taken to avoid mistakes. This ultimately portrays the business as forward-thinking, trustworthy, and credible.[53]

- Several resources should be consulted. However, the best guide to exporting for the small business comes from the US government.[54]

- The SBA is a great place to start to find information to help a business break into the global game. The information on exporting and importing is comprehensive and easily understood.

- The US government portal Export.gov provides online trade resources and one-on-one assistance for global businesses. Export.gov provides particularly helpful information on regulations, licenses, and trade data and analysis. Trade data can help a business identify the best countries to target for exports. A business can gauge the size of the market for a product or a service and develop a pricing strategy to become competitive.[55]

- The US International Trade Commission offers market information, trade leads, and overseas business contacts. Trade professionals are available to help a business every step of the way with information counseling that can reduce costs, risks, and the mystery of exporting.[56]

- The US Department of Commerce provides trade opportunities for US business, export-related assistance, and market information.[57]

- Information about protecting intellectual property abroad can be found at http://www.stopfakes.gov. This is important because counterfeiting and piracy cost the world economy approximately $650 billion per year.[58]

Other sources to be consulted include people in the same business or industry, industry-specific magazines, trade fairs, seminars,[59] and export training and technical assistance that is available to small businesses through the states and the federal government. The Federation of International Trade Associations is a global trade portal that provides trade leads, market research, links to eight thousand import/export websites, and even travel services. WorldBid.com describes itself as the largest network of international trade marketplaces in the world, providing trade leads and new business contacts.[60]

The Internet makes it possible to gather and view tremendous amounts of information. If a business is thinking seriously about going global, there is no better time to take advantage of this quick-and-easy access than now.

Video Link 18.3 Knowing the Export Environment

Government experts identify challenges and debunk some myths.

Business Assessment: Are You Ready?

It is important to honestly self-evaluate a business to determine whether it is really ready to go global or not…or at least not yet.[61]If a business is thinking about expanding globally, it is probably already doing something right to have reached this point. However, that does not preclude the importance of assessing its strengths and its weaknesses to determine the approach that should be taken in the global market.[62] This will be true no matter what role e-commerce plays in a business. Even a micromultinational business should assess its strengths and its weaknesses, although its instantaneous presence as a global business means that the assessment must be done at start-up and then must continue as products and services move from country to country.

There are several issues that should be addressed. The following are some of the questions that should be asked:[63][64][65][66]

- Why is a business successful in the domestic market? What is its growth rate? What are its strengths?

- What products have export potential? Do the products fill a niche that is exclusive to the US market? Are they packaged in a way that can be understood by non-English-speaking consumers? Do they violate any cultural taboos or contain ingredients that will prohibit their sale in a foreign market? Identify the key selling features of the products, identify the needs that they satisfy, and identify any selling constraints.

- What are the competitive advantages of a particular business’s products over other domestic and international businesses?

- What competitive products are sold abroad and by whom?

- Does the product require complementary goods and technologies? If so, who will provide them?

- How will the business provide customer service?

- Can production handle a wider demographic? Can the business increase output without sacrificing quality?

- Does the business have the money to market globally?

- Is the entire business (including all staff) committed to a global effort?

If a product is an industrial good, a business will want to know things such as what firms will likely use it, whether its use or life might be affected by climate, and whether geography will present transportation problems that will affect purchase. In the case of a consumer good, a business will want to know who will consume it; how frequently it will be purchased; whether it will be restricted abroad; whether climate or geography will negatively impact accessibility for purchase; and—perhaps most importantly—whether it conflicts with traditions, taboos, habits, or the beliefs of customers abroad.[67]

A helpful tool to assess readiness is the export questionnaire available at www.export.gov/begin/assessment.asp. This questionnaire highlights characteristics common to successful exporters and identifies areas that need to be strengthened to improve export activities.

Video Link 18.4 Where Will Your Next Customer Come From?

Small businesses looking to grow should look beyond US borders to find new customers.

Marketing

Just as it is necessary to offer a different marketing mix (see Figure 18.2 "The Marketing Mix") for different target markets, it will generally be necessary to adapt the marketing mix to the global market in general and different countries in particular. A business’s unique value proposition (the set of benefits offered to customers to satisfy their needs and wants consisting of some combination of products, services, information, and experiences)[68] is what will differentiate one marketplace offering from the competition. Given the more diversified competition in the global marketplace, identifying the value proposition is even more critical—and most likely more difficult—than in the domestic market.[69]

Figure 18.2 The Marketing Mix

Product

The ideal situation is when a product developed for the US market can be sold in a foreign country without any changes. Although some kinds of products can be introduced with no changes (e.g., cameras, consumer electronics, and many machine tools),[70]most products usually have to be altered in some way to meet conditions in a foreign market.[71] From a small business perspective, the owner will want to market products that do not require drastic changes to be accepted. Relatively minor packaging changes, such as size or the language on the package, can be made inexpensively, but more drastic changes should be avoided. If a product must be changed drastically to market it globally, conduct an in-depth cost analysis to determine whether the additional costs will outweigh the anticipated benefits.[72] If a product is a food or a beverage, for example, is the business prepared to make the changes necessary to appeal to widely varying tastes? [73]

Products need to be adapted for many reasons, including the following:[74][75]

- Different physical or mandated requirements must be met (e.g., electrical goods will need to be rewired for different voltage systems).

- The legal, economic, political, technological, and climatic requirements of the local marketplace vary (e.g., varying laws will set specific packaging sizes and safety and quality standards).

- The product or the company name must translate flawlessly to the new target market so that it does not convey an unintended, perhaps very negative, meaning. One of the most well-known examples of a translation blunder is the Chevy Nova. In Spanish, “nova” means “no go.”

- The package label may need to be changed. Imagine the horror of a well-known baby food producer that introduced small jars of baby food in Africa when it found out that the consumers inferred from the baby picture on the jars that the jars contained ground-up babies. This shows us that even big companies can make big mistakes.

- A change in flavor or fragrance may be necessary to bring a product in line with what is expected in a culture. The pine and hints of ammonia or chlorine scents that are popular in the United States were flops in Japan because many Japanese sleep on the floor on futons. With their heads so close to the floor, a citrus scent is more pleasing.

The less economically developed a market happens to be, the greater may be the need for product adaptation. Research has found that only one in ten products can be marketed in developing countries without some kind of product adaptation.[76]

Cultural Differences

It is important to know that cultural and social differences are intertwined with the perceived value and importance that a market places on a product.[77] “A product is more than a physical item: It is a bundle of satisfactions (or utilities) that the buyer receives. These include its form, taste, color, odor, and texture; how it functions in use; the package; the label; the warranty; the manufacturer’s and retailer’s servicing; the confidence or prestige enjoyed by the brand; the manufacturer’s reputation; the country of origin; and any other symbolic utility received from the possession or use of the goods. In short, the market relates to more than a product’s physical form and primary function.”[78]

The values, customs, rituals, language, and taboos within a culture will determine the acceptability of a product or a service. Cultural sensitivity is particularly important in cyberspace. Website visitors may come from anywhere in the world. Icons and gestures that seem friendly to US visitors may shock people from other cultures. For example, a high-five hand gesture would be insulting to a visitor from Greece.[79] Knives and scissors should not be given as gifts in South America because they symbolize the severing of a friendship. [80]

The psychological attributes of a product (features that have little to do with the primary function of the product but add value to customer satisfaction, e.g., color, size, design, brand name, and price)[81] can also vary across cultures, and the meaning and the value assigned to those attributes can be positive or negative. It may be necessary to adapt the nonphysical features of the product to maximize the positive meanings and eliminate the negative ones.[82] When Coca-Cola, the number one global brand, introduced Diet Coke to Japan, it found that Japanese women do not like to admit to dieting. Further, the idea of diet was associated with medicine and sickness. Coca-Cola ended up changing the name to Coke Light.[83] This happened in Europe as well, so if a product is associated with weight loss, a business must be very careful with its marketing.

The Package

The package for a product includes its design, colors, labeling, trademarks, brand name, size, product information, and the actual packaging materials. There are many reasons why a package may have to be adapted for a particular country. There may be laws that stipulate a specific type of bottle or can, package sizes, measurement units, extraheavy packaging, and the use of particular words on the label.[84] In some cases, the expense of package adaptation may be cost prohibitive for entering a market. Consider the following examples:[85]

- In Japan, a poorly packaged product is seen as an indicator of product quality.

- Prices are required to be printed on the labels in Venezuela, but putting prices on labels or in any way suggesting the retail price in Chile is illegal.

- A soft-drink company from the United States incorporated six-point stars as decoration on its package labels. But it had inadvertently offended some of its Arab customers who interpreted the stars as symbolizing pro-Israeli sentiment.

- Soft drinks are sold in smaller sizes in Japan to accommodate the smaller Japanese hand.

- Descriptive words such as giant or jumbo on a package or a label may be illegal in some countries.

The message here is clear. Before going global with a product, examine the packaging so that each element is in compliance with appropriate laws and regulations so that nothing will offend prospective customers.

Global Packaging

Canada’s oldest candymaker, Ganong Brothers, is located about one mile from Maine. The company chairman, David Ganong, can see the US border from his office window. You would think it would be easy for Ganong Brothers to sell to the US market. Not so. In Canada, nutritional labels read 5 mg, with a space between the number and the unit of measurement. Ganong’s jellybeans cannot get into America unless the label reads 5mg, without the space. This difference, as well as differences in Canada’s nutritional guidelines, means that Ganong must produce and package its US products separately, which reduces its efficiency. Small differences can and do have a significant effect on cross-border trade. This may be the reason why there is not as much trade between the United States and Canada as you would think.[86] This notwithstanding, however, Canada remains the number one exporting destination for US small businesses.[87]

The Business Website

As part of product preparations, a business will need to make its website ready for international business. Remember that the website is a very cost-effective way to sell a product or a service across borders. Here are four ways to ready the website:[88]

- Internationalize website content. A business must account for language differences, and cultural differences may require different graphics and different colors. One way to deal with the additional costs is to translate text or provide country-specific sites only for the country or countries where the most products are sold. One organization that provides resources to help businesses localize their products and resources is the Globalization and Localization Association.

- Calculate the buyer’s costs and estimate shipping. Shipping internationally will take longer, is more complicated, and will be more expensive than shipping domestically. Fortunately, there are shipping management software packages available that will automatically figure the costs and delivery times for overseas orders, giving a close estimate. Large shipping carriers, such as UPS and FedEx, offer such software; other companies include E4X Inc., eCustoms, and Kewill Systems Plc.[89]

- Optimize site and search marketing for international web visitors. With the increase in cross-border selling, websites can be optimized for visitors from specific countries, and techniques can be used to attract international visitors through search engines and search ads. This is a growing specialty among search marketers. A business should definitely check out the cost of hiring such a marketer as a consultant. It would be well worth the investment.

- Comply with government export regulations. A business does not need government approval to sell most goods and services across international borders. There are, of course, notable exceptions. For example, the US government restricts defense or military goods, and agricultural, plant, and food items may have restrictions or special labeling requirements. Such restrictions should be addressed on the website. It may be necessary to restrict the sale of certain products to certain countries only.

Video Link 18.5 Finding Your First Customer

To find the first customer, visit the selected country.

Translation Blunders in Global Marketing

We often hear it said that something was lost in the translation. Here are some global marketing examples of translation blunders. Something important to note is that most of these blunders were committed by the “big guys,” companies that are extremely marketing-savvy—proof positive that no one is immune from this kind of error.

- When Coca-Cola was first translated phonetically into Chinese, the result was a phrase that meant “bite the wax tadpole.” When Coca-Cola discovered the error, the company was able to find a close phonetic equivalent that could be loosely translated as “happiness in the mouth.”[90]

- When Pope John Paul II visited Miami in 1987, an ambitious entrepreneur wanted to sell t-shirts with the logo, “I saw the Pope” in Spanish. The entrepreneur forgot that the definite article in Spanish has two genders. Instead of printing “El Papa” (“the Pope”), he printed “La Papa” (“the potato”). Needless to say, there was no market for t-shirts that read “I saw the potato.”[91]

- Sunbeam got into trouble when it did not change the name of its Mist-Stick curling iron when marketing it in Germany. As it turned out, “mist” is German slang for manure. Not surprisingly, German women did not want to use a manure stick in their hair.[92]

- A proposed new soap called “Dainty” in English came out as “aloof” in Flemish (Belgium), “dimwitted” in Farsi (Iran), and “crazy person” in Korean. The product was dropped.[citation redacted per publisher request]. The company either did not have the resources to research a new name or did not want to take the time and incur the costs to do so.

- Kellogg’s Bran Buds sounded like “burned farmer” in Swedish.[93]

Given that misunderstanding foreign languages can destroy a brand, it is worth the investment to hire someone who is proficient in the native language in the intended market—including the use of slang. This will help a small business avoid a fatal mistake because it does not have the resources of the big companies to fix the mistakes.[94] This concern must be extended to the web presence as well because the website is an integral part of the product.

Price

Pricing for the global market is not an easy thing to do. Many factors must be taken into account, the first of which are traditional price considerations: fixed and variable costs, competition, company objectives, proposed positioning strategies, the target group, and willingness to pay.[95] Add to these factors things such as the additional costs that are incurred due to taxes, tariffs, transportation, retailer margin, and currency fluctuation risks;[96][97] the nature of the product or industry, the location of production facility, and the distribution system;[98] the psychological effects of price; the rest of the marketing mix; and the price transparency created by the Internet[99] and a business can begin to appreciate the challenges of global price setting. About the only thing that can be seen as a certainty is that a small business should expect the price of its product or service to be different, usually higher, in a foreign market.[100] The specifics of that difference need to be worked out carefully, with thorough analysis.

Setting the right price for a product or a service is critical to success. It will be a challenge to navigate the pricing waters of each different country—to learn why, for example, a product sells for $16 in the United States but $23 in Britain.

Place

As challenging as distribution may be for a small business in the domestic market, it is even more so for the global market. No matter the product, it has to go through a distribution process—the physical handling and distribution of goods, the passage of ownership or title, and the buying and selling negotiations between producers and middlemen and middlemen and customers.[101] It would make sense to be able to take advantage of existing transportation systems, retailers, and suppliers to sell goods and provide services. Unfortunately, adequate distribution systems do not exist in all countries, so a business will need to develop ways to get products to customers in as cost-effective a manner as possible.[102]

Video Link 18.6 Getting Your Product from Here to There

Small businesses rely on freight forwarding and shipping experts to move products around the world.

Before deciding on a channel or channels of distribution, a business needs information. The following are some basic questions as a starting point:

- Is the selected market dominated by major retailers or is the retail sector made up of small independent retailers?[103]

- How many intermediaries will be involved? In Japan, for example, a product must go through approximately five different types of wholesalers before it reaches the final consumer.[104]

- Can we use the manufacturer, wholesaler, retailer, or consumer channel or can we export directly to a retailer?

- Should we work with a foreign partner? Unless a business plans to establish a retail operation on foreign soil, it will need to establish business-to-business (B2B) sales relationships. Then products can be sold directly to foreign retailers or foreign distributors who will sell to those retailers. A foreign partner can provide valuable insights about local import regulations, product marketability, and local customs. The US Department of Commerce website contains directories of foreign buyers.[105] Small businesses excel at forming strategic partnerships.[106]

- Where can we attend a trade show or a trade mission? Going to these events can help a business find distribution channels.

- Is the Internet commonly used to distribute my product?

Video Link 18.7 Understanding Partnerships and Distributors

Partnerships help many thriving US businesses overseas.

Video Link 18.8 Identifying Marketing Channels/Activities

How research and planning inform business growth.

In the final analysis, the behavior of distribution channel members will be the result of the interaction between cultural, economic, political, legal, and marketing environments. A small business that is looking to go global—or is already there—will encounter channel structures that range from a minimally developed marketing infrastructure, such as in emerging markets, to highly complex, multilayered systems, such as in Japan.[107]

When deciding to enter the global marketplace, a determination must be made as to whether the current channel structure in the selected country (or countries) will meet the business’s needs or whether some additional arrangements will be needed. The means of distribution will necessarily be a country-by-country decision. No matter the arrangement, however, figure on the costs being greater than in the United States.

Promotion

It is understandable that a small business owner may want to use the same integrated marketing communications (IMC) programs used in the home market to inform customers in foreign markets and persuade them to buy. This “one voice” approach offers the advantage of enabling a business or a product to gain broader recognition in the global marketplace; it also helps reduce costs, minimize redundancies in personnel, and maximize the speed of implementation.[108][109] However, things are not that easy. Cultural, social, language, and legal differences from country to country will usually make it necessary to modify IMC messages to not offend current or prospective customers. Modification is more of a challenge for the small business because the resources needed to make the changes are more limited.

A business communicates with its customers through some combination of its website, advertising, publicity, public relations, sales promotion, sales personnel, e-mail, and social media. The actual mix will be a function of the selected country or countries. For example, in some less-developed countries, the major portion of the promotional effort in rural and less-accessible parts of the market is sales promotion; in other markets, product sampling works especially well when the product concept is new or has a very small market share.[110] In Saudi Arabia, there is an appreciation for fancy packaging, and point-of-sale advertising elicits the best reaction.[111] However, the appropriateness of IMC activities for a small business will depend on the product being marketed, the industry in which it is competing, and the country in which it hopes to sell the product.

Of all the four Ps, decisions involving advertising are thought to be those most often affected by cultural differences in foreign markets. Consumers respond in terms of their culture, style, feelings, value systems, attitudes, beliefs, and perceptions. Because advertising’s function is to interpret or translate the qualities of products and services in terms of consumer needs, wants, desires, and aspirations, emotional appeals, symbols, persuasive approaches, and other characteristics in an advertisement must coincide with cultural norms if the ad is to be effective.[112]

Examples abound of international advertising mistakes that have offended different cultures. Three are presented here. Although they are linked to large corporations, there are lessons to be learned by small businesses. No business is immune from making mistakes from time to time.

- Burger King ran in-store ads for three restaurants in Spain that depicted the Hindu goddess Lakshami on top of a ham sandwich. The caption read, “a snack that is sacred.” Many Hindus are vegetarian and were offended by the ad. Burger King pulled it.[113]

- Burger King ran a campaign in Europe for the Texican Whopper that featured a lanky American cowboy; a short, round Mexican draped in a cape resembling Mexico’s flag; and the caption, “the taste of Texas with a little spicy Mexican.” There was an immediate uproar, with the Mexican ambassador to Spain objecting publicly.[114]

- During a time when Fiat was trying to take advantage of auto sales growth in China, it released an ad in Italy in which actor Richard Gere drove a Lancia Delta from Hollywood to Tibet. The ad did not air in China, but it caused an online uproar nonetheless. Richard Gere is hated in China because he is an outspoken supporter of the Dalai Lama. His selection as the Fiat spokesperson was a major faux pas by Fiat.[115]

The reality of international advertising is that its cost and the effort required to prepare and place the ads correctly may be prohibitive for most small businesses, therefore pushing the emphasis on other elements of the IMC mix. However, a business will not know that for sure until it does the proper research before making a decision. Consider the characteristics of the target market, how the market uses media in that country, and which media are actually available. Some countries do not have commercial television, and some do not have advertising in newspapers. There will be newspaper and magazine circulation differences from country to country; in countries with a low literacy rate, radio and television advertising (if available) will be more effective than print media.[116]

Fortunately, small businesses that want to go global can look to social media for assistance. The social web is a low-cost way to catapult a small business brand into the global arena.[117] Facebook, the most popular social networking site in the world, has developed a self-serve advertising tool that has created the greatest interest among small businesses that might not have had the means to launch a global advertising campaign before. This would be a good place to start—along with a map of the world’s most popular media applications country by country and culture by culture, which is available at www.appappeal.com/the-most-popular-app-per-country/social-networking.

No matter the mix of the IMC program, and no matter whether a business is business-to-consumer (B2C) or B2B, the way a business communicates internationally will be a major determinant of success. Each IMC component is a communication channel in its own right. A business must consider the appropriateness of each message in each channel. For example, is the message adequate? Does it contain correct cultural interpretations? Are the colors and graphics right? In the case of advertising, have the media been chosen that match the behavior of the intended audience? Have you correctly assessed the needs and wants or the thinking processes of the target market?[118]

Careful consideration of these and other communication issues will not guarantee success, but it should help reduce the chances of making a major marketing blunder.

Legal and Political Issues

It is impossible for any small business to know all the laws that pertain to exporting from the United States. Thus it is important to consult an attorney who is knowledgeable about the legal implications of globalization: international trade laws, tax laws, local regulations,[119] international border restrictions, customs rules, and duties and taxes.[120]

To varying degrees, each small business must be concerned with the following. However, this list is not exhaustive; it is a sampling only.

- The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act makes it illegal for companies to pay bribes to foreign officials, candidates, or political parties. The challenge for all US businesses is that bribery is a common business practice in many countries, even though it is illegal.[121] Interestingly, private business bribes are tax deductible in Germany as long as the German businessperson discloses both his or her identity and the recipient of the bribe(s). Although it is supposedly rarely used, it is available.[122]

- Specific licenses and permits are required or additional paperwork must be completed if the following specific products are exported or imported: agricultural products, automobiles (not a likely product for a small business), chemicals, defense products, food and beverage products, industrial goods, and pharmaceutical and biotechnology products.[123]

- There is heightened sensitivity since September 11, 2011, about exporting products that could even remotely be used in a military or a terrorist capacity.[124]

- Brand names, trademarks, products, processes, designs, and formulas are among the more valuable assets a small business can possess. These need to be protected—domestically and internationally. US officials estimate that $300 billion of intellectual property assets are ripped off every year.[125]

- There are commercial laws within countries related to marketing, environmental issues, and antitrust.

Video Link 18.9 Understanding Legal Considerations

Important legal considerations for small businesses that want to go global.

In addition to legal considerations, no small business can conduct global business without understanding the influence of the political environments in which it will be operating.[126] Every nation has the sovereign right to grant or withhold permission to do business within its political boundaries and control where its citizens do business, so the political environment of countries is necessarily a critical concern to any small business.[127] Political issues include the stability of government policies (a stable and friendly government being the ideal), the forms of government (with some being more open to foreign commerce than others), political parties and their influence on economic policy, the degree of nationalism (the greater the nationalism, the greater the bias against foreign business and investments may be), fear and/or animosity that is targeted toward a specific country, and trade disputes.[128] One or all these things create political risk that must be assessed. The most severe political risk is confiscation, the seizing of a company’s assets without payment.[129]

Currency Exchange Issues

The exchange rate is the rate at which one country’s currency can be exchanged for the currency of another country.[130] For example, assume that on a particular day, $1 exchanged for 0.75643 euros and 49.795 Indian rupees.[131][132] These exchange rates then changed the next day, when $1 exchanged for 0.6891 euros and 49.845 Indian rupees, meaning that the value of the US dollar increased in value with respect to the euro and decreased in value against the Indian rupee. Currency exchange rates change daily, and they are important because currency fluctuations can present additional problems for the small business looking to go global. The appreciation and depreciation of a currency will have an effect on the prices of goods and services. For example, as the dollar declines in value against the euro, the price of goods and services from the European Union for US customers will increase, likely reducing their purchases.[133] The following are other implications of exchange rate fluctuations:[134][135]

- Inattention to exchange rates in long-term contracts could result in large unintended discounts.

- Rapid and unexpected currency fluctuations can make pricing in local currencies very difficult.

- Shifts in exchange rates can influence the attractiveness of various business decisions, not the least of which is whether doing business in a particular country is worthwhile.

Different strategies may be needed when the dollar is weak versus when it is strong. For example, when the US dollar is weak, a business should stress price benefits. When the dollar is strong, a business can engage in nonprice competition by improving quality, delivery, and after-sale services.[136] To navigate these challenging currency exchange waters, it will be necessary to tap into accounting and finance expertise.

Sources of Financing

How a business finances an export project is often a critical factor in its success. Financing decisions extend to working capital and export transactions. Working capital is needed to finance operations before and after a sale, and money is needed to sustain a business until it is paid for the goods and services that have been provided (export transactions). The International Trade Association in the US Department of Commerce identifies the following factors as important to consider when making financing decisions.[137]

- The need for financing to make the sale. Offering favorable payment terms can make a product more competitive.

- The length of time the product is being financed. The term of the loan required determines how long a business will have to wait before the buyer pays for the product, which will influence the choice of how to finance the transaction.

- The cost of different methods of financing. Interest rates and fees will vary, and a business should probably expect to assume some of the financing costs. Before providing an invoice to the buyer, a business must understand how these costs will affect price and profit.

- The risks associated with financing the transaction. The riskier the transaction, the more difficult and costly it will be for a business to finance it because there will likely be a higher chance for default. The level of risk will be influenced by several things, not the least of which is the political and economic stability of the buyer’s country. In risky situations, the financing provider may require the most secure method of payment—a letter of credit or export credit insurance.

- The need for preshipment financing and postshipment working capital. Working capital could experience unexpected and severe strains with the production of an unusually large order or a surge of orders. Inadequate working capital can limit exporting growth—even during normal periods.

Where to Go

Small businesses have reported that problems with access to financing for their exporting operations are a major barrier to exporting. The difficulties they experience in obtaining both trade finance and working capital often prevent small businesses from financing purchases by foreign buyers. This encourages foreign buyers to choose suppliers that are able to extend credit. Small businesses must also face the perception of lending institutions that they are a higher risk than larger companies coupled with a lack of familiarity with exporting by community banks.[138]

Despite any anticipated difficulties, small businesses need to find export financing. They can look for financing in several places. The first place to look is internally. Does it already have the funds to finance global efforts? If the answer is yes, then all is well. This was the case for Center Rock, the small business featured at the beginning of this chapter. If the answer is no, which will most likely be the case, it will be necessary to look for external financing. A range of options is available for small businesses to consider (see Table 18.3 "Sources of Export Financing for the Small Business"). As you will see, most financing sources are available from the government. A small business must become familiar with the financing, insurance, and grant programs that are available to help it finance transactions and carry out export operations.[139]

Table 18.3 Sources of Export Financing for the Small Business

| Source | Information |

|---|---|

| Extending credit to foreign buyers working with commercial banks | Liberal financing can enhance export competitiveness, but extending credit must be weighed carefully. Some commercial bank services used to finance domestic business, including revolving lines of credit for working capital, are often needed to finance export sales until payment is received. However, commercial banks prefer to establish an ongoing business relationship instead of financing solely on the basis of an individual order. Most US banks do not lend against export orders, export receivables, or letters of credit. |

| Export Express 7(a) Loan Programs | Offered by the SBA, this streamlined program helps small businesses develop or expand their export markets. A business may be able to obtain SBA-backed financing for loans and lines of credit up to $500,000. |

| Export Working Capital Program (EWCP) 7(a) Loan Programs | This SBA loan program targets small businesses that are able to generate export sales but need additional working capital to support these sales. The SBA provides lenders guarantees of up to 90 percent on export loans to ensure that qualified exporters do not lose viable export sales due to a lack of working capital. |

| International Trade Loan Program 7(a) Loan Programs | Loans are available for businesses that plan to start or continue exporting or have been adversely affected by competition from imports. The loan proceeds must enable the borrower to be in a better position to compete. The program offers borrowers a maximum SBA-guaranteed portion of $1.75 million. |

| Export-Import Bank | An independent federal agency that provides working capital loan guarantees, export-credit insurance, and other forms of financing for US exporters of all sizes. The funds are aimed at offsetting the added risks of doing business abroad, from complex trade rules to unpaid bills. |

| Using export intermediaries | Many export intermediaries, for example, trading companies and export management companies, can help finance export sales. The intermediaries may provide short-term financing or may purchase the goods to be exported directly from the manufacturer, thus eliminating any risks to the manufacturer that are associated with the export transaction as well as the need for financing. |

Video Link 18.10 Financing

Some of the ways small businesses can finance their exporting projects.

Key Takeaways

- Expanding into global markets introduces new complexities into small business operations.

- The decision to go global should be based on an assessment of the ways to export, an analysis of the industry and a particular company, marketing and cultural factors, legal and political conditions, currency exchange rates, and sources of financing.

- There are two basic ways to export: direct or indirect. In direct exporting, a small business exports directly to a customer who is interested in buying the product. Indirect exporting involves using a middleman for marketing and selling the product in the target market.

- Industry analysis involves looking at where an industry currently is and the trends and directions predicted over the next three years so that a business can try to determine how competitive an industry is in the global market.

- It is important to honestly self-evaluate a business to determine whether it is ready to go global or not.

- It will generally be necessary to adapt the marketing mix to the global market in general and different countries in particular.

- Legal issues include international trade laws, tax laws, and local regulations.

- No small business can conduct global business without understanding the influence of the political environments in which it will be operating.

- Currency exchange rates are important because currency fluctuations can present additional problems for a small business that is looking to go global. In particular, the appreciation and depreciation of a currency will have an effect on the prices of goods and services.

- How a business finances an export project is often a critical factor in its success.

- Working capital is needed before and after the sale, and money is needed until the goods and services that have been provided have been paid for.

- Many—perhaps most—of the sources for small business exporting activity are governmental.

Exercises

- Comment on the following: a small business owner firmly believes that because a product is successful in Chicago, Illinois, it will be successful in Tokyo or Berlin.[143] Be as specific as you can in your comments.

- There has been tremendous growth in online business, which has introduced new elements to the legal climate of global business. Patents, brand names, copyrights, and trademarks are difficult to monitor because there are no boundaries with the Internet. What steps could a small business take to protect its trademarks and brands in this environment? Prepare at least five suggestions.[144]

- Find a local small business that exports its products. Talk to the owner about his or her experiences. Ask questions such as the following: What convinced you to export? How did you decide on the product(s) to export? Did you have to adapt your product(s) in any way? What were the greatest barriers you had to face?

Key Management Decisions and Considerations

Learning Objectives

- Understand the organizational support that will be needed for exporting activities.

- Understand the need to select the best market to entry.

- Identify and describe each possible market entry strategy.

- Learn about the different approaches to getting paid.

- Appreciate the importance of business etiquette when traveling to visit customers.

- Understand the importance of an export plan.

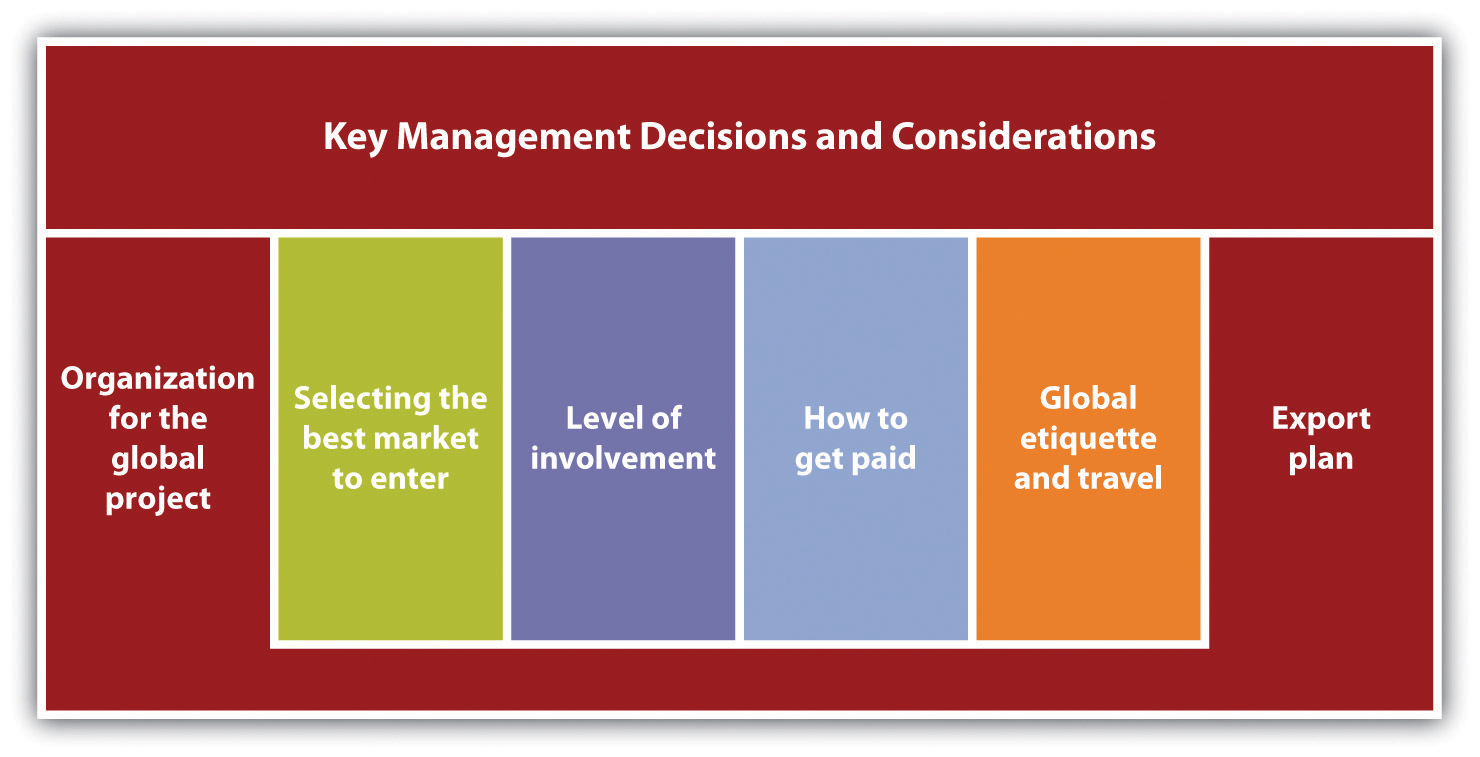

After a business decides to jump into the global pond, several key management decisions must be made (Figure 18.3 "Management Decisions"). Among them are organization for the global project, selecting the best market to enter, the level of involvement desired, and how to get paid. There should also be consideration of global etiquette and travel.

Figure 18.3 Management Decisions

Several important questions about the global venture should be answered before making any management decisions or considerations.[145] Less than satisfactory answers to these questions may put the global venture in jeopardy.

- Do the company’s reasons for pursuing export markets include solid objectives, such as increasing sales volume or developing a broader, more stable customer base, or are the reasons frivolous, such as the owner wants an excuse to travel?

- How committed is top management to the export effort? Is it viewed as a quick fix for a slump in domestic sales? Will the company neglect its export customers if domestic sales pick up?

- What are management’s expectations for the export effort? Will they expect export operations to become self-sustaining quickly? If so, how quickly?

- What level of return on investment is expected from the export project?

Organization for the Global Project

It will be important to have some kind of structure or team within the business to handle the global side of the business. It does not have to be large, but it should be dedicated to ensuring that export sales are adequately serviced, and there should be a clear indication of who will be responsible for the organization and staffing.[146] Having the right resources for the global effort is critical, so a business should make the most of skills already held by staff members, for example, languages or familiarity with a range of foreign currencies. If these and other needed skills are not already available on staff, a small business should seek assistance from external experts.[147]

Other organizational issues that small businesses must address before going abroad include the following:[148][149][150]

- Getting internal buy-in. Because going overseas to do business is a larger undertaking than many businesses realize, make sure that senior management and the people who are responsible for implementing and supporting the overseas effort know what the goals are and what is expected of them with respect to oversight and management. Knowing how much senior management time should be and could be allocated is an important part of getting internal buy-in. Look for support from people in all functions of the business.

- Making sure that the full costs of overseas hiring are understood. If people from overseas will be hired, employment regulations and practices are very different. For example, outside the United States, employment benefits often represent a larger percentage of an employee’s salary than in the United States; in the European Union, for example, a full-blown employment contract is needed, not just an offer letter. This tilts the balance of power to the employee at the expense of the company, making termination very difficult. Understanding the full ramifications of hiring people outside the United States has significant implications for a company’s financial success.

- Thinking about how the business will manage overseas employees’ expectations. Different time zones and countries wreak havoc with keeping employees on the same page. Employees hired locally may have very different ideas about what is considered acceptable than a US employee does. Unless expectations and responsibilities are clearly conveyed at the beginning, problems will undoubtedly arise. They may anyway, but perhaps they will not be as serious.

Market Selection

A business must select the best market(s) to enter. The three largest markets for US products are Canada, Japan, and Mexico, but these countries may not be the largest or best markets for a particular product.[151] If a business is not sure where the best place for doing global business is, one good approach is to find out where domestic competitors have been expanding internationally. Although moving into the same market(s) may make good sense, a good strategy might also be to go somewhere else. Three key US government databases that can identify the countries that represent significant export potential for a product are as follows:[152]

- The SBA’s Automated Trade Locator Assistance System

- Foreign Trade Report FT925

- The US Department of Commerce’s National Trade Data Bank

After identifying the country or countries that may offer the best market potential for a product, serious market research should be conducted. A business should look at all the following factors: demographic, geographic, political, economic, social, cultural, market access, distribution, production, and the existence or absence of tariffs and nontariff trade barriers. Tariffs are taxes imposed on imported goods so that the price of imported goods increases to the level of domestic goods. Tariffs can be particularly critical in selecting a particular country because the tariff may make it impossible for a US small business to profitably sell its products in a particular country.

Nontariff trade barriers are laws or regulations enacted by a country to protect its domestic industries against foreign competition.[153] These barriers include such things as import licensing requirements; fees; government procurement policies; border taxes; and packaging, labeling, and marking standards.[154]

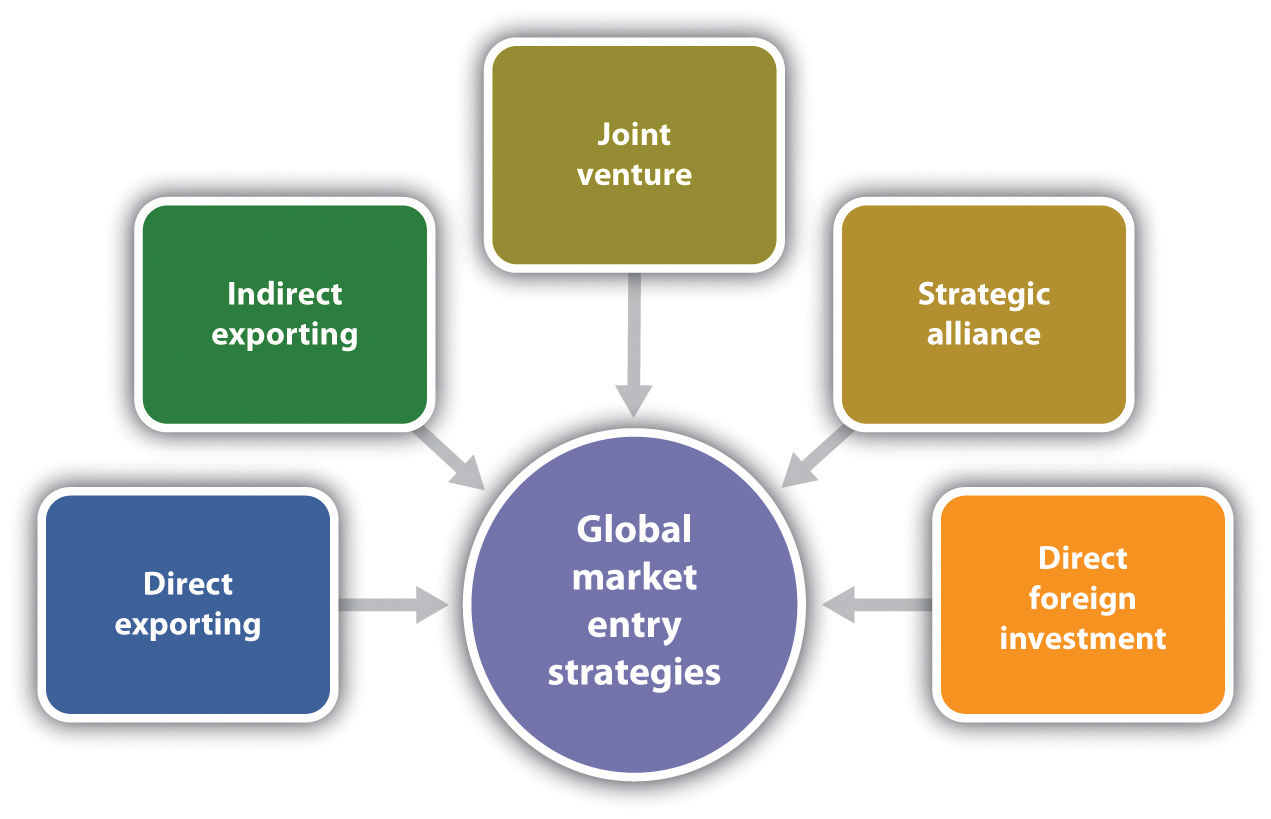

Market Entry Strategies

A small business must decide how it wants to enter the selected foreign market(s). Several choices might look attractive for a business (see Figure 18.4 "Examples of Export Market Entry Strategies"). Direct and indirect exporting, strategic alliances, joint ventures, and direct foreign investment are discussed in this section. The benefits and risks associated with each strategy depend on many factors. Among them are the type of product or service being produced; the need for product or service support; and the foreign economic, political, business, and cultural environment to be penetrated. A firm’s level of resources and commitment and the degree of risk it is willing to incur will help determine the strategy that the business thinks will work best.[155]

Figure 18.4 Examples of Export Market Entry Strategies

- Joint venture (JV) is a partnership with a foreign firm formed to achieve a specific goal or operate for a specific period of time. A legal entity is created, with the partners agreeing to share in the management of the JV, and each partner holds an equity position. Each company retains its separate identity. Among the benefits are immediate market knowledge and access, reduced risk, and control over product attributes. On the negative side, JV agreements across national borders can be extremely complex, which requires a very high level of commitment by all parties.[156][157][158] Because some countries have restrictions on the foreign ownership of corporations, a JV may be the only way a small business can purchase facilities in another country.[159]

- Strategic alliance is very similar to a JV in that it is a partnership formed to create competitive advantage on a worldwide basis.[160] An agreement is signed between two corporations, but a separate business entity is not created.[161] The business relationship is based on cooperation out of mutual need, and there is shared risk in achieving a common objective. Growing at a rate of about 20 percent per year, strategic alliances are created for many reasons (e.g., opportunities for rapid expansion into new markets, reduced marketing costs, and strategic competitive moves).[162] “Small businesses excel at forming strategic partnerships and alliances which make them look bigger than they are and offer their customers a global reach.[163]

- Direct foreign investment is exactly what it sounds like: investment in a foreign country. If a business is interested in manufacturing locally to take advantage of low-cost labor, gain access to raw materials, reduce the high costs of transportation to market, or gain market entry, direct foreign investment is something to be considered. However, the complicated mix of considerations and risks—for example, the growing complexity and contingencies of contracts and degree of product differentiation—makes decisions about foreign investments increasingly difficult.[164]

Getting Paid

Being paid in full and on time is of obvious importance to a business, so the level of risk that it is willing to assume in extending credit to customers is a major consideration.[165] The credit of a buyer will always be a concern, but potentially more worrisome is the lessened recourse a business will have when it comes to collecting unpaid international debts. Extra caution must be exercised. Both the business owner and the buyer must agree on the terms of the sale in advance.[166]

The primary methods of payment for international transactions are payment in advance (the most secure), letters of credit, documentary collection (drafts), consignment, and open account (the least secure), which are described as follows:[167][168]

- Cash in advance. This is the ideal method of payment because a company is relieved of collection problems and has immediate use of the money. Unfortunately, it tends to be an option only when the manufacturing process is specialized, lengthy, or capital intensive and requires partial or progress payments. Wire transfers are commonly used, and many exporters accept credit cards.