Accounting and Finances

12 Chapter 12: Personal Finances

Personal Finances

Do you wonder where your money goes? Do you have trouble controlling your spending? Have you run up the balances on your credit cards or gotten behind in your payments and hurt your credit rating? Do you worry about how you’ll pay off your student loans? Would you like to buy a new car or even a home someday and you’re not sure where the money will come from? If you do have extra money, do you know how to invest it? Do you know how to find the right job for you, land an offer, and evaluate the company’s benefits? If these questions seem familiar to you, you could benefit from help in managing your personal finances. This chapter will provide that help.

Where Does Your Money Go?

Learning Objectives

- Offer advice to someone who is burdened with debt.

- Offer advice to someone whose monthly bills are too high.

Let’s say that you’re single and twenty-eight. You have a good education and a good job—you’re pulling down $60K working with a local accounting firm. You have $6,000 in a retirement savings account, and you carry three credit cards. You plan to buy a house (maybe a condo) in two or three years, and you want to take your dream trip to the world’s hottest surfing spots within five years (or, at the most, ten). Your only big worry is the fact that you’re $70,000 in debt, mostly from student loans, your car loan, and credit card debt. In fact, even though you’ve been gainfully employed for a total of six years now, you haven’t been able to make a dent in that $70,000. You can afford the necessities of life and then some, but you’ve occasionally wondered if you’re ever going to have enough income to put something toward that debt.[1]

Now let’s suppose that while browsing through a magazine in the doctor’s office, you run across a short personal-finances self-help quiz. There are two sets of three statements each, and you’re asked to check off each statement with which you agree:

- Part 1

- If I didn’t have a credit card in my pocket, I’d probably buy a lot less stuff.

- My credit card balance usually goes up at the holidays.

- If I really want something that I can’t afford, I put it on my credit card or sign up for a payment plan.

- Part 2

- I can barely afford my apartment.

- Whenever something goes wrong (car repairs, doctors’ bills), I have to use my credit card.

- I almost never spend money on stuff I don’t need, but I always seem to owe a balance on my credit card bill.

At the bottom of the page, you’re asked whether you agreed with any of the statements in Part 1 and any of the statements in Part 2. It turns out that you answered yes in both cases and are thereby informed that you’re probably jeopardizing your entire financial future.

Unfortunately, personal-finances experts tend to support the author of the quiz: if you agreed with any statement in Part 1, you have a problem with splurging; if you agreed with any statement in Part 2, your monthly bills are too high for your income.

Building a Good Credit Rating

So, you have a financial problem: according to the quick test you took, you’re a splurger and your bills are too high for your income. How does this put you at risk? If you get in over your head and can’t make your loan or rent payments on time, you risk hurting your credit—your ability to borrow in the future.

Let’s talk about your credit. How do potential lenders decide whether you’re a good or bad credit risk? If you’re a poor credit risk, how does this affect your ability to borrow, or the rate of interest you have to pay, or both? Here’s the story. Whenever you use credit, those you borrow from (retailers, credit card companies, banks) provide information on your debt and payment habits to three national credit bureaus: Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion. The credit bureaus use the information to compile a numerical credit score, generally called a FICO score; it ranges from 300 to 900, with the majority of people falling in the 600–700 range. (Here’s a bit of trivia to bring up at a dull party: FICO stands for Fair Isaac Company—the company that developed the score.) In compiling the score, the credit bureaus consider five criteria: payment history—do you pay your bills on time? (the most important), total amount owed, length of your credit history, amount of new credit you have, and types of credit you use. The credit bureaus share their score and other information about your credit history with their subscribers.

So what does this do for you? It depends. If you paid your bills on time, carried only a reasonable amount of debt, didn’t max out your credit cards, had a history of borrowing, hadn’t applied for a bunch of new loans, and borrowed from a mix of lenders, you’d be in good shape. Your FICO score would be high and lenders would like you. Because of your high credit score, they’d give you the loans you asked for at reasonable interest rates. But if your FICO score is low (perhaps you weren’t so good at paying your bills on time), lenders won’t like you and won’t lend you money (or would lend it to you at high interest rates). A low FICO score can raise the amount you have to pay for auto insurance and cell phone plans and can even affect your chances of renting an apartment or landing a particular job. So it’s very, very, very (the last “very” is for emphasis) important that you do everything possible to earn a high credit score. If you don’t know your score, here is what you should do: go to https://www.quizzle.com/ and request a free copy of your credit report.

As a young person, though, how do you build a credit history that will give you a high FICO score? Your means for doing this changed in 2009 with the passage of the Credit CARD Act, federal legislation designed to stop credit card issuers from treating its customers unfairly.[2] Based on feedback from several financial experts, Emily Starbuck Gerson and Jeremy Simon of CreditCards.com compiled the following list of ways students can build good credit.[3]

- Become an authorized user on your parents’ account. According to the rules set by the Credit CARD Act, if you are under age twenty-one and do not have independent income, you can get a credit card in your own name only if you have a cosigner (who is over twenty-one and does have an income). This is a time when a parent can come in handy. Your parent could add you to his or her credit card account as an authorized user. Of course, this means your parent will know what you’re spending your money on (which could make for some interesting conversations). But, on the plus side, by piggybacking on your parent’s card you are building good credit (assuming, of course, that your parent pays the bill on time).

- Obtain your own credit card. If you can show the credit card company that you have sufficient income to pay your credit card bill, you might be able to get your own card. It isn’t as easy to get a card as it was before the passage of the Credit CARD Act, and you won’t get a lot of goodies for signing up (as was true before), but you stand a chance.

- Get the right card for you. If you meet the qualifications to get a credit card on your own, look for the best card for you. Although it sounds enticing to get a credit card that gives you frequent flyer miles for every dollar you spend, the added cost for this type of card, including higher interest charges and annual fees, might not be worth it. Look for a card with a low interest rate and no annual fee. As another option, you might consider applying for a retail credit card, such as a Target or Macy’s card.

- Use the credit card for occasional, small purchases. If you do get a credit card or a retail card, limit your charges to things you can afford. But don’t go in the other direction and put the card in a drawer and never use it. Your goal is to build a good credit history by showing the credit reporting agencies that you can handle credit and pay your bill on time. To accomplish this, you need to use the card.

- Avoid big-ticket buys, except in case of emergency. Don’t run up the balance on your credit card by charging high-cost, discretionary items, such as a trip to Europe during summer break, which will take a long time to pay off. Leave some of your credit line accessible in case you run into an emergency, such as a major car repair.

- Pay off your balance each month. If you cannot pay off the balance on your credit card each month, this is likely a signal that you’re living beyond your means. Quit using the card until you bring the balance down to zero. When you’re first building credit, it’s important to pay off the balance on your card at the end of each month. Not only will this improve your credit history, but it will save you a lot in interest charges.

- Pay all your other bills on time. Don’t be fooled into thinking that the only information collected by the credit agencies is credit card related. They also collect information on other payments including phone plans, Internet service, rental payments, traffic fines, and even library overdue fees.

- Don’t cosign for your friends. If you are twenty-one and have an income, a nonworking, under-age-twenty-one friend might beg you to cosign his credit card application. Don’t do it! As a cosigner, the credit card company can make you pay your friend’s balance (plus interest and fees) if he fails to meet his obligation. And this can blemish your own credit history and lower your credit rating.

- Do not apply for several credit cards at one time. Just because you can get several credit cards, this doesn’t mean that you should. When you’re establishing credit, applying for several cards over a short period of time can lower your credit rating. Stick with one card.

- Use student loans for education expenses only, and pay on time. For many, student loans are necessary. But avoid using student loans for noneducational purposes. All this does is run up your debt. When your loans become due, consolidate them if appropriate and don’t miss a payment.

What if you’ve already damaged your credit score—what can you do to raise it? Do what you should have done in the first place: pay your bills on time, pay more than the minimum balance due on your credit cards and charge cards, keep your card balances low, and pay your debts off as quickly as possible. Also, scan your credit report for any errors. If you find any, work with the credit bureau to get them corrected.

Understand the Cost of Borrowing

Because your financial problem was brought on, in part, because you have too much debt, you should stop borrowing. But, what if your car keeps breaking down and you’re afraid of getting stuck on the road some night? So, you’re thinking of replacing it with a used car that costs $10,000. Before you make a final decision to incur the debt, you should understand its costs. The rate of interest matters a lot. Let’s compare three loans at varying interest rates: 6, 10, and 14 percent. We’ll look at the monthly payment, as well as the total interest paid over the life of the loan.

| $10,000 Loan for 4 Years at Various Interest Rates | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Interest Rate | 6% | 10% | 14% |

| Monthly Payment | $235 | $254 | $273 |

| Total Interest Paid | $1,272 | $2,172 | $3,114 |

If your borrowing interest rate is 14 percent, rather than 6 percent, you’ll end up paying an additional $1,842 in interest over the life of the loan. Your borrowing cost at 14 percent is more than twice as much as it is at 6 percent. The conclusion: search for the best interest rates and add the cost of interest to the cost of whatever you’re buying before deciding whether you want it and can afford it. If you have to borrow the money for the car at the 14 percent interest rate, then the true cost of the car isn’t $10,000, but rather $13,114.

Now, let’s explore the complex world of credit cards. First extremely important piece of information: not all credit cards are equal. Second extremely important piece of information: watch out for credit card fees! Credit cards are a way of life for most of us. But they can be very costly. Before picking a credit card, do your homework. A little research can save you a good deal of money. There are a number of costs you need to consider:

- Finance charge. The interest rate charged to you often depends on your credit history; those with good credit get the best rates. Some cards offer low “introductory” rates—but watch out; these rates generally go up after six months.

- Annual fee. Many credit cards charge an annual fee: a yearly charge for using the card. You can avoid annual fees by shopping around (though there can be trade-offs: you might end up paying a higher interest rate to avoid an annual fee).

- Over-limit fee. This fee is charged whenever you exceed your credit line.

- Late payment fee. Pretty self-explanatory, but also annoying. Late payment fees are common for students; a study found students account for 6 percent of all overdraft fees.[4] One way to decrease the chance of paying late is to call the credit card company and ask them to set your payment due date for a time that works well for you. For example, if you get paid at the end of the month, ask for a payment date around the 10th of the month. Then you can pay your bill when you get paid and avoid a late fee.

- Cash advance fee. While it’s tempting to get cash from your credit card, it’s pretty expensive. You’ll end up paying a fee (around 3 percent of the advance), and the interest rate charged on the amount borrowed can be fairly high.

An alternative to a credit card is a debit card, which pulls money out of your checking account whenever you use the card to buy something or get cash from an ATM. These cards don’t create a loan when used. So, are they better than credit cards? It depends—each has its advantages and disadvantages. A big advantage of a credit card is that it helps you build credit. A disadvantage is that you can get in over your head in debt and possibly miss payments (thereby incurring a late payment fee). Debit cards help control spending. Theoretically, you can’t spend more than you have in your checking account. But be careful—if you don’t keep track of your checking account balance, it’s easy to overdraft your account when using your debit card. Prior to July 2010, most banks just accepted purchases or ATM withdrawals even if a customer didn’t have enough money in his or her account to cover the transaction. The banks didn’t do this to be nice, and they didn’t ask customers if they wanted this done—they just overdrafted the customer’s account and charged the customer a hefty overdraft fee of around $35 through what they call an “overdraft protection program”.[5] Overdraft fees can be quite expensive, particularly if you used the card to purchase a hamburger and soda at a fast-food restaurant.

The Federal Reserve changed the debit card rules in 2010, and now banks must get your permission before they enroll you in an overdraft protection program.[6] If you opt in (agree), things work as before: You can spend or take out more money through an ATM machine than you have in your account, and the bank lets you do this. But it charges you a fee of about $30 plus additional fees of $5 per day if you don’t cover the overdraft in five days. If you don’t opt in, the bank will not let you overdraft your account. The downside is that you could get embarrassed at the cash register when your purchase is rejected or at a restaurant when trying to pay for a meal. Obviously, you want to avoid being charged an overdraft fee or being embarrassed when paying for a purchase. Here are some things you can do to decrease the likelihood that either would happen:[7]

- Ask your bank to e-mail or text you when your account balance is low.

- Have your bank link your debit card account to a savings account. If more money is needed to cover a purchase, the bank will transfer the needed funds from your savings to your checking account.

- Use the online banking feature offered by most banks to check your checking account activity.

A Few More Words about Debt

What should you do now to turn things around—to start getting out of debt? According to many experts, you need to take two steps:

- Cut up your credit cards and start living on a cash-only basis.

- Do whatever you can to bring down your monthly bills.

Figure 12.1 Visa Credit Card

Living on a cash-only basis is the first step in getting debt under control.[8]

Step 1 in this abbreviated two-step personal-finances “plan” is probably the easier of the two, but taking even this step can be hard enough. In fact, a lot of people would find it painful to give up their credit cards, and there’s a perfectly logical reason for their reluctance: the degree of pain that one would suffer from destroying one’s credit cards probably stands in direct proportion to one’s reliance on them.

As of May 2011, total credit card debt in the United States is about $780 billion, out of $2.5 trillion in total consumer debt. Closer to home, one recent report puts average credit card debt per U.S. household at $16,000 (up 100 percent since 2000). The 600 million credit cards held by U.S. consumers carry an average interest rate on these cards of 15 percent.[9] Why are these numbers important? Primarily because, on average, too many consumers have debt that they simply can’t handle. “Credit card debt,” says one expert on the problem, “is clobbering millions of Americans like a wrecking ball,”[10] and if you’re like most of us, you’d probably like to know whether your personal-finances habits are setting you up to become one of the clobbered.

If, for example, you’re worried that your credit card debt may be overextended, the American Bankers Association suggests that you ask yourself a few questions:[11]

-

-

Do I pay only the minimum month after month?

-

Do I run out of cash all the time?

-

Am I late on critical payments like my rent or my mortgage?

-

Am I taking longer and longer to pay off my balance(s)?

-

Do I borrow from one credit card to pay another?

-

If such habits as these have helped you dig yourself into a hole that’s steadily getting deeper and steeper, experts recommend that you take three steps as quickly as possible:[12]

- Get to know the enemy. You may not want to know, but you should collect all your financial statements and figure out exactly how much credit card debt you’ve piled up.

- Don’t compound the problem with late fees. List each card, along with interest rates, monthly minimums, and due dates. Bear in mind that paying late fees is the same thing as tossing what money you have left out the window.

- Now cut up your credit cards (or at least stop using them). Pay cash for everyday expenses, and remember: swiping a piece of plastic is one thing (a little too easy), while giving up your hard-earned cash is another (a little harder).

And, if you find you’re unable to pay your debts, don’t hide from the problem, as it will not go away. Call your lenders and explain the situation. They should be willing to work with you in setting up a payment plan. If you need additional help, contact a nonprofit credit assistance group such as the National Foundation for Credit Counseling (http://www.nfcc.org).

Why You Owe It to Yourself to Manage Your Debts

Now, it’s time to tackle step 2 of our recommended personal-finances miniplan: do whatever you can to bring down your monthly bills. As we said, many people may find this step easier than step 1—cutting up your credit cards and starting to live on a cash-only basis.

If you want to take a gradual approach to step 2, one financial planner suggests that you perform the following “exercises” for one week:[13]

- Keep a written record of everything you spend and total it at week’s end.

- Keep all your ATM receipts and count up the fees.

- Take $100 out of the bank and don’t spend a penny more.

- Avoid gourmet coffee shops.

Among other things, you’ll probably be surprised at how much of your money can become somebody else’s money on a week-by-week basis. If, for example, you spend $3 every day for one cup of coffee at a coffee shop, you’re laying out nearly $1,100 a year. If you use your ATM card at a bank other than your own, you’ll probably be charged a fee that can be as high as $3. The average person pays more than $60 a year in ATM fees, and if you withdraw cash from an ATM twice a week, you could be racking up $300 in annual fees. As for your ATM receipts, they’ll tell you whether, on top of the fee that you’re charged by that other bank’s ATM, your own bank is also tacking on a surcharge.[14][15][16][17]

If this little exercise proves enlightening—or if, on the other hand, it apparently fails to highlight any potential pitfalls in your spending habits—you might devote the next week to another exercise:

- Put all your credit cards in a drawer and get by on cash.

- Take your lunch to work.

- Buy nothing but groceries and gasoline.

- Use coupons whenever you go to the grocery store (but don’t buy anything just because you happen to have a coupon).

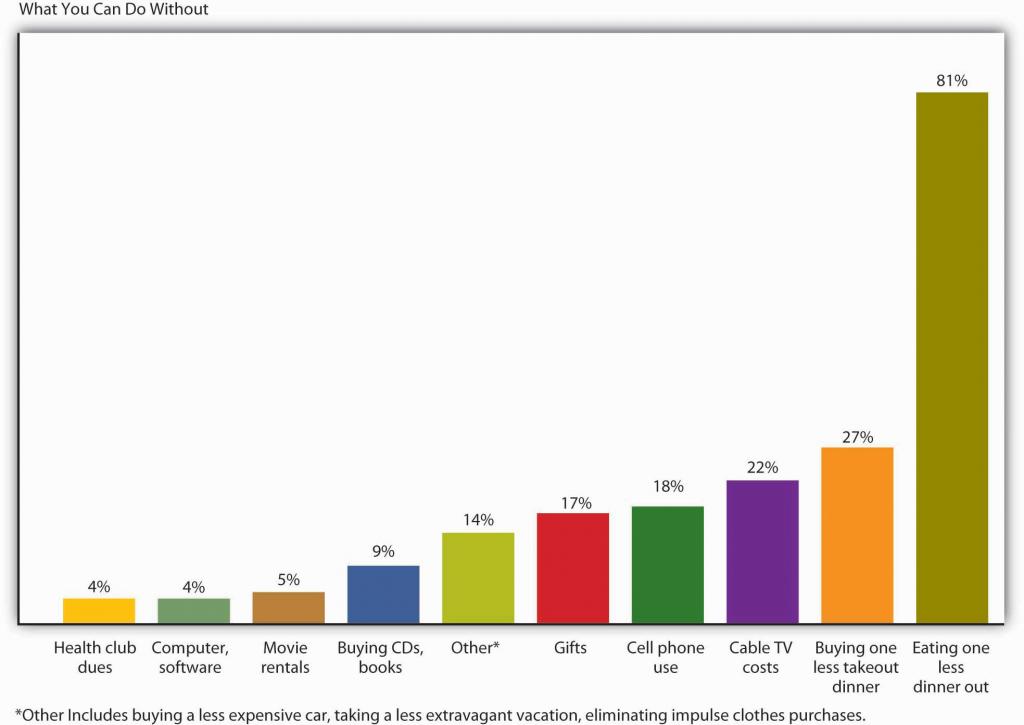

The obvious question that you need to ask yourself at the end of week 2 is, “how much did I save?” An equally interesting question, however, is, “what can I do without?” One survey asked five thousand financial planners to name the two expenses that most consumers should find easiest to cut back on. Figure 12.2 “Reducible Expenses” shows the results.

Figure 12.2 Reducible Expenses

You may or may not be among the American consumers who buy thirty-five million cans of Bud Light each and every day, or 150,000 pounds of Starbucks coffee, or 2.4 million Burger King hamburgers, or 628 Toyota Camrys. Yours may not be one of the 70 percent of U.S. households with an unopened consumer-electronics product lying around.[18] And you may or may not be ready to make some major adjustments in your personal-spending habits, but if, at age twenty-eight, you have a good education and a good job, a $60,000 income, and a $70,000 debt—by no means an implausible scenario—there’s a very good reason why you should think hard about controlling your modest share of that $2.5 trillion in U.S. consumer debt: your level of indebtedness will be a key factor in your ability—or inability—to reach your longer-term financial goals, such as home ownership, a dream trip, and, perhaps most important, a reasonably comfortable retirement.

The great English writer Samuel Johnson once warned, “Do not accustom yourself to consider debt only as an inconvenience; you will find it a calamity.” In Johnson’s day, you could be locked up for failing to pay your debts; there were even so-called debtors’ prisons for the purpose, and we may suppose that the prospect of doing time for owing money was one of the things that Johnson had in mind when he spoke of debt as a potential “calamity.” We don’t expect that you’ll ever go to prison on account of indebtedness, and we won’t suggest that, say, having to retire to a condo in the city instead of a tropical island is a “calamity.” We’ll simply say that you’re more likely to meet your lifetime financial goals—whatever they are—if you plan for them. What you need to know about planning for and reaching those goals is the subject of this chapter.

Key Takeaways

- Before buying something on credit, ask yourself whether you really need the goods or services, can afford them, and are willing to pay interest on the purchase.

- Whenever you use credit, those you borrow from provide information on your debt and payment habits to three national credit bureaus.

- The credit bureaus use the information to compile a numerical credit score, called a FICO score, which they share with subscribers.

- The credit bureaus consider five criteria in compiling the score: payment history, total amount owed, length of your credit history, amount of new credit you have, and types of credit you use.

-

As a young person, you should do the following to build a good credit history that will give you a high FICO score.

- Become an authorized user on your parents’ account.

- Obtain your own credit card

- Get the right card for you.

- Use the credit card for occasional, small purchases

- Avoid big-ticket buys, except in case of emergency.

- Pay off your balance each month.

- Pay all your other bills on time.

- Don’t cosign for your friends.

- Do not apply for several credit cards at one time.

- Use student loans for education expenses only, and pay on time.

- To raise your credit score, you should pay your bills on time, pay more than the minimum balance due, keep your card balances low, and pay your debts off as quickly as possible. Also, scan your credit report for any errors and get any errors fixed.

- If you can’t pay your debt, explain your situation to your lenders and see a credit assistance counselor.

- Before you incur a debt, you should understand its costs. The interest rate charged by the lender makes a big difference in the overall cost of the loan.

- The costs associated with credit cards include finance charges, annual fees, over-limit fees, late payment fees, and cash advance fees.

- The Federal Reserve changed the debit card rules in 2010 and now banks must get your permission before they enroll you in an overdraft protection program.

- If you have a problem with splurging, cut up your credit cards and start living on a cash-only basis.

- If your monthly bills are too high for your income, do whatever you can to bring down those bills.

Exercise

(AACSB) Analysis

There are a number of costs associated with the use of a credit card, including finance charges, annual fee, over-limit fee, late payment fee, and cash advance fee. Identify these costs for a credit card you now hold. If you don’t presently have a credit card, go online and find an offer for one. Check out these costs for the card being offered.

Financial Planning

Learning Objectives

- Define personal finances and financial planning.

- Explain the financial planning life cycle.

- Discuss the advantages of a college education in meeting short- and long-term financial goals.

- Describe the steps you’d take to get a job offer and evaluate alternative job offers, taking benefits into account.

- Understand the ways to finance a college education.

Before we go any further, we need to nail down a couple of key concepts. First, just what, exactly, do we mean by personal finances? Finance itself concerns the flow of money from one place to another, and your personal finances concern your money and what you plan to do with it as it flows in and out of your possession. Essentially, then, personal finance is the application of financial principles to the monetary decisions that you make either for your individual benefit or for that of your family.

Second, monetary decisions work out much more beneficially when they’re planned rather than improvised. Thus our emphasis on financial planning—the ongoing process of managing your personal finances in order to meet goals that you’ve set for yourself or your family.

Financial planning requires you to address several questions, some of them relatively simple:

- What’s my annual income?

- How much debt do I have, and what are my monthly payments on that debt?

Others will require some investigation and calculation:

- What’s the value of my assets?

- How can I best budget my annual income?

Still others will require some forethought and forecasting:

- How much wealth can I expect to accumulate during my working lifetime?

- How much money will I need when I retire?

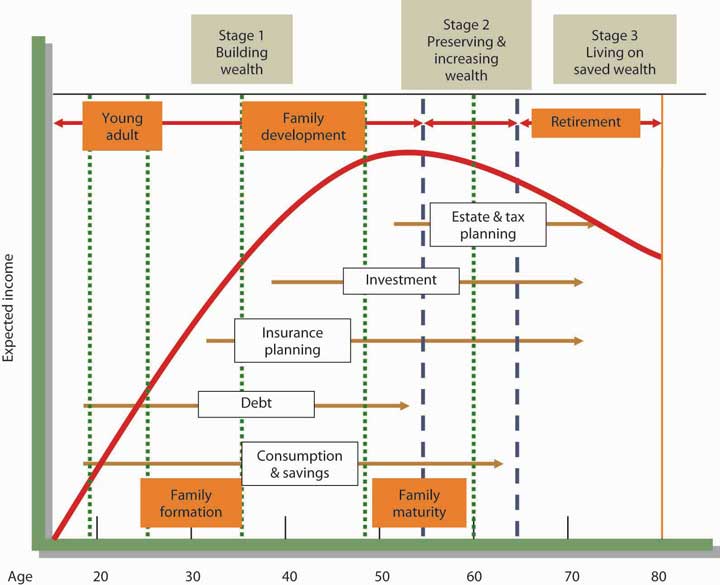

The Financial Planning Life Cycle

Another question that you might ask yourself—and certainly would do if you were a professional in financial planning—is something like, “How will my financial plans change over the course of my life?” Figure 12.3 “Financial Life Cycle” illustrates the financial life cycle of a typical individual—one whose financial outlook and likely outcomes are probably a lot like yours.[19] As you can see, our diagram divides this individual’s life into three stages, each of which is characterized by different life events (such as beginning a family, buying a home, planning an estate, retiring). At each stage, too, there are recommended changes in the focus of the individual’s financial planning:

- In stage 1, the focus is on building wealth.

- In stage 2, the focus shifts to the process of preserving and increasing the wealth that one has accumulated and continues to accumulate.

- In stage 3, the focus turns to the process of living on (and, if possible, continuing to grow) one’s saved wealth.

Figure 12.3 Financial Life Cycle

At each stage, of course, complications can set in—say, changes in such conditions as marital or employment status or in the overall economic outlook. Finally, as you can also see, your financial needs will probably peak somewhere in stage 2, at approximately age fifty-five, or ten years before typical retirement age.

Choosing a Career

Until you’re eighteen or so, you probably won’t generate much income; for the most part, you’ll be living off your parents’ wealth. In our hypothetical life cycle, however, financial planning begins in the individual’s early twenties. If that seems like rushing things, consider a basic fact of life: this is the age at which you’ll be choosing your career—not only the sort of work you want to do during your prime income-generating years, but also the kind of lifestyle you want to live in the process.[20]

What about college? Most readers of this book, of course, have decided to go to college. If you haven’t yet decided, you need to know that college is an extremely good investment of both money and time.

Table 12.1 “Education and Average Income”, for example, summarizes the findings of a study conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau.[21] A quick review shows that people who graduate from high school can expect to increase their average annual earnings by about 49 percent over those of people who don’t, and those who go on to finish college can expect to generate 82 percent more annual income than that. Over the course of the financial life cycle, families headed by those college graduates will earn about $1.6 million more than families headed by high school graduates who didn’t attend college. (With better access to health care—and, studies show, with better dietary and health practices—college graduates will also live longer. And so will their children.)[22]

Table 12.1 Education and Average Income

| Education | Average income | Percentage increase over next-highest level |

|---|---|---|

| High school dropout | $20,873 | — |

| High school diploma | $31,071 | 48.9% |

| College degree | $56,788 | 82.8% |

| Advanced higher-education degree | $82,320 | 45.0% |

And what about the debt that so many people accumulate to finish college? For every $1 that you spend on your college education, you can expect to earn about $35 during the course of your financial life cycle.[23] At that rate of return, you should be able to pay off your student loans (unless, of course, you fail to practice reasonable financial planning).

Naturally, there are exceptions to these average outcomes. You’ll find English-lit majors stocking shelves at 7-Eleven, and you’ll find college dropouts running multibillion-dollar enterprises. Microsoft cofounder Bill Gates dropped out of college after two years, as did his founding partner, Paul Allen. Current Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer finished his undergraduate degree but quit his MBA program to join Microsoft (where he apparently fit in among the other dropouts in top management). It’s always good to remember, however, that though exceptions to rules (and average outcomes) occasionally modify the rules, they invariably fall far short of disproving them: in entrepreneurship as in most other walks of adult life, the better your education, the more promising your financial future. One expert in the field puts the case for the average person bluntly: educational credentials “are about being employable, becoming a legitimate candidate for a job with a future. They are about climbing out of the dead-end job market”.[24]

Finally, does it make any difference what you study in college? To a perhaps surprising extent, not necessarily. Some career areas, such as engineering, architecture, teaching, and law, require targeted degrees, but the area of study designated on your degree often doesn’t matter much when you’re applying for a job. If, for instance, a job ad says, “Business, communications, or other degree required,” most applicants and hires will have those “other” degrees. When poring over résumés for a lot of jobs, potential employers look for the degree and simply note that a candidate has one; they often don’t need to focus on the particulars.[25]

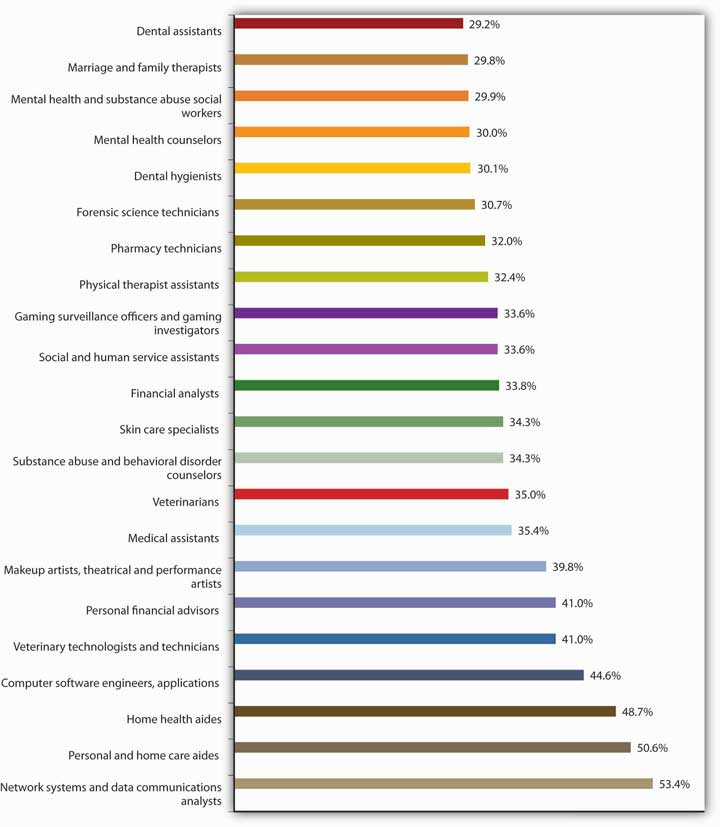

This is not to say, however, that all degrees promise equal job prospects. Figure 14.4 “Top 25 Fastest-Growing Jobs, 2006–2016”, for example, summarizes a U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projection of the thirty fast-growing occupations for the years 2006–2016. Veterinary technicians and makeup artists will be in demand as never before, but as you can see, occupational prospects are fairly diverse.[26]

Figure 12.4 Top 25 Fastest-Growing Jobs, 2006–2016

Nor, of course, do all degrees pay off equally. In Table 12.2 “College Majors and Average Annual Earnings”, we’ve extracted the findings of a study conducted by the National Science Foundation on the earnings of individuals with degrees in various undergraduate fields.[27][28] Clearly, some degrees—notably in the engineering fields—promise much higher average earnings than others. Chemical engineers, for instance, can earn nearly twice as much as elementary school teachers, but there’s a catch: if you graduate with a degree in chemical engineering, your average annual salary will be about $67,000 if you can find a job related to that degree; if you can’t, you may have to settle for as much as 40 percent less.[29] (Supermodel Cindy Crawford cut short her studies in chemical engineering because there was more money to be made on the runway.)

Table 12.2 College Majors and Average Annual Earnings

| Major | Average Earnings with Bachelor’s Degree | Major | Average Earnings with Bachelor’s Degree |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical engineering | $67,425 | History | $45,926 |

| Aerospace engineering | $65,649 | Biology | $45,532 |

| Computer engineering | $62,527 | Nursing | $45,538 |

| Physics | $62,104 | Psychology | $43,963 |

| Electrical engineering | $61,534 | English | $43,614 |

| Mechanical engineering | $61,382 | Health technology | $42,524 |

| Industrial engineering | $61,030 | Criminal justice | $41,129 |

| Civil engineering | $58,993 | Physical education | $40,207 |

| Accounting | $56,637 | Secondary education | $39,976 |

| Finance | $55,104 | Fine arts | $38,857 |

| Computer science | $52,615 | Philosophy | $38,239 |

| Business management | $52,321 | Dramatic arts | $37,091 |

| Marketing | $51,107 | Music | $36,811 |

| Journalism | $46,835 | Elementary education | $34,564 |

| Information systems | $46,519 | Special education | $34,196 |

In short, when you’re planning what to do with the rest of your life, it’s a good idea to check into the fine points and realities, as well as the statistical data. If you talk to career counselors and people in the workforce, you might be surprised by what you learn about the relationship between certain college majors and various occupations. Onetime Hewlett-Packard CEO Carly Fiorina majored in medieval history and philosophy.

Financing a College Education

Let’s revisit one of the facts included in the earlier discussion: for every $1 that you spend on your college education, you can expect to earn about $35 during the course of your financial life cycle. And let’s say you’re convinced (as you should be) that getting a college degree is a wise financial choice. You still have to deal with the cost of getting your degree. We’re sure this won’t come as a surprise: attending college is expensive—tuition and fees have gone up sharply, the cost of books has skyrocketed, and living expenses have climbed. Many students can attend college only if they receive some type of financial aid. Though the best way to learn what aid is available to you is to talk with a representative in the financial aid office at your school, this section provides an overview of the types of aid offered to students. Students finance their education through scholarships, grants, education loans, and work-study programs.[30] We’ll explore each of these categories of aid:

- Scholarships, which don’t have to be repaid, are awarded based on a number of criteria, including academic achievement, athletic or artistic talent, special interest in a particular field of study, ethnic background, or religious affiliation. Scholarships are generally funded by private donors such as alums, religious institutions, companies, civic organizations, professional associations, and foundations.

- Grants, which also don’t have to be repaid, are awarded based on financial need. They’re funded by the federal government, the states, and academic institutions. An example of a common federal grant is the Pell Grant, which is awarded to undergraduate students based on financial need. The maximum Pell Grant award for the 2011–12 award year (July 1, 2011, to June 30, 2012) is $5,550.[31]

- Education loans, which must be repaid, are available to students from various sources, including the federal government, states, and academic institutions. While recent problems in the credit markets have made college loans more difficult to obtain, most students are able to get the loans they need.[32] The loans offered directly to undergraduate students by the federal government include the need-based, subsidized Federal Stafford, the non–need-based unsubsidized Federal Stafford, and the need-based Federal Perkins loans. With the exception of the unsubsidized Federal Stafford, no interest accrues while the student is enrolled in college at least part time. There are also a number of loans available to parents of students, such as the Federal Parent PLUS program. Under this program, parents can borrow federally guaranteed low-interest loans to fund their child’s education.

- Work-study is a federally sponsored program that provides students with paid, part-time jobs on campus. Because the student is paid based on work done, the funds received don’t have to be repaid.

Find a Great Job

As was highlighted earlier, your financial life cycle begins at the point when you choose a career. Building your career takes considerable planning. It begins with the selection of a major in college and continues through graduation as you enter the workforce full time. You can expect to hold a number of jobs over your working life. If things go as they should, each job will provide valuable opportunities and help you advance your career. A big challenge is getting a job offer in your field of interest, evaluating the offer, and (if you have several options) selecting the job that’s right for you.[33]

Getting a Job Offer

Most likely your college has a career center. The people working there can be a tremendous help to you as you begin your job search. But most of the work has to be done by you. Like other worthwhile projects, your job search project will be very time-consuming. As you get close to graduation, you’ll need to block out time to work on this particularly important task.

The first step is to prepare a résumé, a document that provides a summary of educational achievements and relevant job experience. Its purpose is to get you an interview. A potential employer will likely spend less than a minute reviewing your résumé, so its content should be concise, clear, and applicable to the job for which you’re applying. For some positions, the person in charge of hiring might read more than a hundred résumés. If you don’t want your résumé kicked out right away, be sure it contains no typographical or grammatical errors. Once you’ve completed your résumé, you can use it to create different versions tailored to specific companies you’d like to work for. Your next step is to write a cover letter, a document accompanying your résumé that explains why you’re sending your résumé and highlights your qualifications. You can find numerous tips on writing résumés and cover letters (as well as samples of both) online. Be sure your résumé is accurate: never lie or exaggerate in a résumé. You could get caught and not get the job (or—even worse—you could get the job, get caught, and then get fired). It’s fairly common practice for companies to conduct background checks of possible employees, and these checks will point out any errors. In effect, says one expert, “you jeopardize your future when you lie about your past”.[34]

After writing your résumé and cover letter, your next task is to create a list of companies you’d like to work for. Use a variety of sources, including your career services office and company Web sites, to decide which companies to put on your list. Visit the “career or employment” section of the company Web sites and search for specific openings.

You could also conduct a general search for positions that might be of interest to you, by doing the following:

- Visiting career Web sites, such as Monster.com, Wetfeet.com, or Careerbuilder.com (which maintain large databases of openings for all geographical areas)

- Searching classified ads in online and print newspapers

- Attending career fairs at your college and in your community

- Signing up with career services to talk with recruiters when they visit your campus

- Contacting your friends, family, and college alumni and letting them know you’re looking for a job and asking for their help

Once you spot a position you want, send your résumé and cover letter (tailored to the specific company and job). Follow up in a few days to be sure your materials got to the right place, and offer to provide any additional information. Keep notes on all contacts.

Figure 12.5 Preparing for an Interview

Preparing well for an interview can make it easier to relax and help the interviewer get to know you.[35]

When you’re invited for an interview, visit to the company’s Web site and learn as much as you can about the company. Practice answering questions you might be asked during the interview, and think up a few pertinent questions to ask your interviewer. Dress conservatively—males should wear a suit and tie and females should wear professional-looking clothes. Try to relax during the interview (though everyone knows this isn’t always easy). Your goal is to get an offer, so let the interviewer learn who you are and how you can be an asset to the company. Send a thank-you note (or thank-you e-mail) to the interviewer after the interview.

Evaluating Job Offers

Let’s be optimistic and say that you did quite well in your interviews, and you have two job offers. It’s a great problem to have, but now you have to decide which one to accept. Salary is important, but it’s clearly not the only factor. You should consider the opportunities the position offers: will you learn new things on the job, how much training will you get, could you move up in the organization (and if so, how quickly)? Also consider quality of life issues: how many hours a week will you have to work, is your schedule predictable (or will you be asked to work on a Friday night or Saturday at the last minute), how flexible is your schedule, how much time do you get off, how stressful will the job be, do you like the person who will be your manager, do you like your coworkers, how secure is the job, how much travel is involved, where’s the company located, and what’s the cost of living in that area? Finally, consider the financial benefits you’ll receive. These could include health insurance, disability insurance, flexible spending accounts, and retirement plans. Let’s talk more about the financial benefits, beginning with health insurance.

- Employer-sponsored health insurance plans vary greatly. Some cover the employee only, while others cover the employee, spouse, and children. Some include dental and eye coverage while others don’t. Most plans require employees to share some of the cost of the medical plan (by paying a portion of the insurance premiums and a portion of the cost of medical care). But the amount that employees are responsible for varies greatly. Given the rising cost of health insurance, it’s important to understand the specific costs associated with a health care plan and to take these costs into account when comparing job offers. More important, it’s vital that you have medical insurance. Young people are often tempted to go without medical insurance, but this is a major mistake. An uncovered, costly medical emergency (say you’re rushed to the hospital with appendicitis) can be a financial disaster. You could end up paying for your hospital and doctor care for years.

- Disability insurance isn’t as well known as medical insurance, but it can be as important (if not more so). Disability insurance pays an income to an insured person when he or she is unable to work for an extended period. You would hope that you’d never need disability insurance, but if you did it would be of tremendous value.

- A flexible spending account allows a specified amount of pretax dollars to be used to pay for qualified expenses, including health care and child care. By paying for these costs with pretax dollars, employees are able to reduce their tax bill.

- There are two main types of retirement plans. One, called a defined benefit retirement plan, provides a set amount of money each month to retirees based on the number of years they worked and the income they earned. This form of retirement plan was once very popular, but it’s less common today. The other, called a defined contribution retirement plan, is a form of savings plan. The employee contributes money each pay period to his or her retirement account, and the employer matches a portion of the contribution. Even when retirement is exceedingly far into the future, it’s financially wise to set aside funds for retirement.

Key Takeaways

- Finance concerns the flow of money from one place to another; your personal finances concern your money and what you plan to do with it as it flows in and out of your possession. Personal finance is thus the application of financial principles to the monetary decisions that you make, either for your individual benefit or for that of your family.

- Financial planning is the ongoing process of managing your personal finances to meet goals that you’ve set for yourself or your family.

-

The financial life cycle divides an individual’s life into three stages, each of which is characterized by different life events. Each stage also entails recommended changes in the focus of the individual’s financial planning:

- In stage 1, the focus is on building wealth.

- In stage 2, the focus shifts to the process of preserving and increasing the wealth that one has accumulated and continues to accumulate.

- In stage 3, the focus turns to the process of living on (and, if possible, continuing to grow) one’s saved wealth.

- According to the model of the financial life cycle, financial planning begins in the individual’s early twenties, the age at which most people choose a career—both the sort of work they want to do during their income-generating years and the kind of lifestyle they want to live in the process.

- College is a good investment of both money and time. People who graduate from high school can expect to improve their average annual earnings by about 49 percent over those of people who don’t, and those who go on to finish college can expect to generate 82 percent more annual income than that. The area of study designated on your degree often doesn’t matter when you’re applying for a job: when poring over résumés, employers often look for the degree and simply note that a candidate has one.

- The first step in your job search is to prepare a résumé, a document that provides a summary of educational achievements and relevant job experience. Your résumé should be concise, clear, applicable to the job for which you are applying, and free of errors and inaccuracies.

- A cover letter is a document that accompanies your résumé and explains why you’re sending your résumé and highlights your qualifications.

-

To conduct a general search for positions that might be of interest to you, you could:

- Visit career Web sites, such as Monster.com, Wetfeet.com, or Careerbuilder.com.

- Search classified ads in online and print newspapers.

- Attend career fairs at your college and in your community.

- Talk with recruiters when they visit your campus.

- Contact people you know, tell them you’re looking for a job, and ask for their help.

- When you’re invited for an interview, you should research the company, practice answering questions you might be asked in the interview, and think up pertinent questions to ask the interviewer.

-

When comparing job offers, consider more than salary. Also of importance are quality of life issues and benefits. Common financial benefits include health insurance, disability insurance, flexible spending accounts, and retirement plans.

- Employer-sponsored health insurance plans vary greatly in coverage and cost to the employee.

- Disability insurance pays an income to an insured person when he or she is unable to work for an extended period of time.

- A flexible spending account allows a specified amount of pretax dollars to be used to pay for qualified expenses, including health care and child care. By paying for these costs with pretax dollars, employees are able to reduce their tax bill.

- There are two main types of retirement plans: a defined benefit plan, which provides a set amount of money each month to retirees based on the number of years they worked and the income they earned, and a defined contribution plan, which is a form of savings plan into which both the employee and employer contribute. A well-known defined contribution plan is a 401(k).

Exercise

(AACSB) Analysis

Think of the type of job you’d like to have. Describe the job and indicate how you’d go about getting a job offer for this type of job. How would you evaluate competing offers from two companies? What criteria would you use in selecting the right job for you?

Time Is Money

Learning Objectives

- Explain compound interest and the time value of money.

- Discuss the value of getting an early start on your plans for saving.

The fact that you have to choose a career at an early stage in your financial life cycle isn’t the only reason that you need to start early on your financial planning. Let’s assume, for instance, that it’s your eighteenth birthday and that on this day you take possession of $10,000 that your grandparents put in trust for you. You could, of course, spend it; in particular, it would probably cover the cost of flight training for a private pilot’s license—something you’ve always wanted but were convinced that you couldn’t afford for another ten or fifteen years. Your grandfather, of course, suggests that you put it into some kind of savings account. If you just wait until you finish college, he says, and if you can find a savings plan that pays 5 percent interest, you’ll have the $10,000 plus another $2,209 to buy a pretty good used car.

The total amount you’ll have— $12,209—piques your interest. If that $10,000 could turn itself into $12,209 after sitting around for four years, what would it be worth if you actually held on to it until you did retire—say, at age sixty-five? A quick trip to the Internet to find a compound-interest calculator informs you that, forty-seven years later, your $10,000 will have grown to $104,345 (assuming a 5 percent interest rate). That’s not really enough to retire on, but after all, you’d at least have some cash, even if you hadn’t saved another dime for nearly half a century. On the other hand, what if that four years in college had paid off the way you planned, so that (once you get a good job) you’re able to add, say, another $10,000 to your retirement savings account every year until age sixty-five? At that rate, you’ll have amassed a nice little nest egg of slightly more than $1.6 million.

Compound Interest

In your efforts to appreciate the potential of your $10,000 to multiply itself, you have acquainted yourself with two of the most important concepts in finance. As we’ve already indicated, one is the principle of compound interest, which refers to the effect of earning interest on your interest.

Let’s say, for example, that you take your grandfather’s advice and invest your $10,000 (your principal) in a savings account at an annual interest rate of 5 percent. Over the course of the first year, your investment will earn $512 in interest and grow to $10,512. If you now reinvest the entire $10,512 at the same 5 percent annual rate, you’ll earn another $537 in interest, giving you a total investment at the end of year 2 of $11,049. And so forth. And that’s how you can end up with $104,345 at age sixty-five.

Time Value of Money

You’ve also encountered the principle of the time value of money—the principle whereby a dollar received in the present is worth more than a dollar received in the future. If there’s one thing that we’ve stressed throughout this chapter so far, it’s the fact that, for better or for worse, most people prefer to consume now rather than in the future. This is true for both borrowers and lenders. If you borrow money from me, it’s because you can’t otherwise buy something that you want at the present time. If I lend it to you, it’s because I’m willing to postpone the opportunity to purchase something I want at the present time—perhaps a risk-free, ten-year U.S. Treasury bond with a present yield rate of 3 percent.

I’m willing to forego my opportunity, however, only if I can get some compensation for its loss, and that’s why I’m going to charge you interest. And you’re going to pay the interest because you need the money to buy what you want to buy. How much interest should we agree on? In theory, it could be just enough to cover the cost of my lost opportunity, but there are, of course, other factors. Inflation, for example, will have eroded the value of my money by the time I get it back from you. In addition, while I would be taking no risk in loaning money to the U.S. government (as I would be doing if I bought that Treasury bond), I am taking a risk in loaning it to you. Our agreed-on rate will reflect such factors.[36]

Finally, the time value of money principle also states that a dollar received today starts earning interest sooner than one received tomorrow. Let’s say, for example, that you receive $2,000 in cash gifts when you graduate from college. At age twenty-three, with your college degree in hand, you get a decent job and don’t have an immediate need for that $2,000. So you put it into an account that pays 10 percent compounded and you add another $2,000 ($167 per month) to your account every year for the next eleven years1. The left panel of Table 12.3 “Why to Start Saving Early (I)” shows how much your account will earn each year and how much money you’ll have at certain ages between twenty-three and sixty-seven. As you can see, you’d have nearly $52,000 at age thirty-six and a little more than $196,000 at age fifty; at age sixty-seven, you’d be just a bit short of $1 million. The right panel of the same table shows what you’d have if you hadn’t started saving $2,000 a year until you were age thirty-six. As you can also see, you’d have a respectable sum at age sixty-seven—but less than half of what you would have accumulated by starting at age twenty-three. More important, even to accumulate that much, you’d have to add $2,000 per year for a total of thirty-two years, not just twelve.

Table 12.3 Why to Start Saving Early (I)[37]

| Savings accumulated from age 23, with deposits of $2,000 annually until age 67 | Savings accumulated from age 36, with deposits of $2,000 annually until age 67 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Annual deposit | Annual interest earned | Total saved at the end of the year | Annual deposit | Annual interest earned | Total saved at the end of the year |

| 23 | $0.00 | $0.00 | $0.00 | $0.00 | $0.00 | $0.00 |

| 24 | $2,000 | $200.00 | $2,200 | $0.00 | $0.00 | $0.00 |

| 25 | $2,000 | $420.00 | $4,620 | $0.00 | $0.00 | $0.00 |

| 30 | $2,000 | $1,897.43 | $20,871.78 | $0.00 | $0.00 | $0.00 |

| 35 | $2,000 | $4,276.86 | $47,045.42 | $0.00 | $0.00 | $0.00 |

| 36 | $0.00 | $4,704.54 | $51,749.97 | $2,000 | $200.00 | $2,200.00 |

| 40 | $0.00 | $6,887.92 | $75,767.13 | $2,000 | $1,221.02 | $13,431.22 |

| 45 | $0.00 | $11,093.06 | $122,023.71 | $2,000 | $3,187.48 | $35,062.33 |

| 50 | $0.00 | $17,865.49 | $196,520.41 | $2,000 | $6,354.50 | $69,899.46 |

| 55 | $0.00 | $28,772.55 | $316,498.09 | $2,000 | $11,455.00 | $126,005.00 |

| 60 | $0.00 | $46,338.49 | $509,723.34 | $2,000 | $19,669.41 | $216,363.53 |

| 65 | $0.00 | $74,628.59 | $820,914.53 | $2,000 | $32,898.80 | $361,886.65 |

| 67 | $0.00 | $90,300.60 | $993,306.53 | $2,000 | $40,277.55 | $442,503.09 |

Here’s another way of looking at the same principle. Suppose that you’re twenty years old, don’t have $2,000, and don’t want to attend college full-time. You are, however, a hard worker and a conscientious saver, and one of your (very general) financial goals is to accumulate a $1 million retirement nest egg. As a matter of fact, if you can put $33 a month into an account that pays 12 percent interest compounded[38], you can have your $1 million by age sixty-seven. That is, if you start at age twenty. As you can see from Table 12.4 “Why to Start Saving Early (II)”, if you wait until you’re twenty-one to start saving, you’ll need $37 a month. If you wait until you’re thirty, you’ll have to save $109 a month, and if you procrastinate until you’re forty, the ante goes up to $366 a month.[39]

Table 12.4 Why to Start Saving Early (II)[40]

| First Payment When You Turn | Required Monthly Payment | First Payment When You Turn | Required Monthly Payment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | $33 | 30 | $109 |

| 21 | $37 | 31 | $123 |

| 22 | $42 | 32 | $138 |

| 23 | $47 | 33 | $156 |

| 24 | $53 | 34 | $176 |

| 25 | $60 | 35 | $199 |

| 26 | $67 | 40 | $366 |

| 27 | $76 | 50 | $1,319 |

| 28 | $85 | 60 | $6,253 |

| 29 | $96 |

The moral here should be fairly obvious: a dollar saved today not only starts earning interest sooner than one saved tomorrow (or ten years from now) but also can ultimately earn a lot more money in the long run. Starting early means in your twenties—early in stage 1 of your financial life cycle. As one well-known financial advisor puts it, “If you’re in your 20s and you haven’t yet learned how to delay gratification, your life is likely to be a constant financial struggle”.[41]

Key Takeaways

- The principle of compound interest refers to the effect of earning interest on your interest.

- The principle of the time value of money is the principle whereby a dollar received in the present is worth more than a dollar received in the future.

- The principle of the time value of money also states that a dollar received today starts earning interest sooner than one received tomorrow.

- Together, these two principles give a significant financial advantage to individuals who begin saving early during the financial-planning life cycle.

Exercise

(AACSB) Analysis

Everyone wants to be a millionaire (except those who are already billionaires). To find out how old you’ll be when you become a millionaire, go to http://www.youngmoney.com/calculators/savings_calculators/millionaire_calculator and input these assumptions:

Age: your actual age

Amount currently invested: $10,000

Expected rate of return (interest rate): 5 percent

Millionaire target age: 65

Savings per month: $500

Expected inflation rate: 3 percent

Click “calculate” and you’ll learn when you’ll become a millionaire (given the previous assumptions).

Now, let’s change things. We’ll go through this process three times. Change only the items described. Keep all other assumptions the same as those listed previously.

- Change the interest rate to 3 percent and then to 6 percent.

- Change the savings amount to $200 and then to $800.

- Change your age from “your age” to “your age plus 5” and then to “your age minus 5.”

Write a brief report describing the sensitivity of becoming a millionaire, based on changing interest rates, monthly savings amount, and age at which you begin to invest.

The Financial Planning Process

Learning Objectives

- Identify the three stages of the personal-finances planning process.

- Explain how to draw up a personal net-worth statement, a personal cash-flow statement, and a personal budget.

We’ve divided the financial planning process into three steps:

- Evaluate your current financial status by creating a net worth statement and a cash flow analysis.

- Set short-term, intermediate-term, and long-term financial goals.

- Use a budget to plan your future cash inflows and outflows and to assess your financial performance by comparing budgeted figures with actual amounts.

Step 1: Evaluating Your Current Financial Situation

Just how are you doing, financially speaking? You should ask yourself this question every now and then, and it should certainly be your starting point when you decide to initiate a more or less formal financial plan. The first step in addressing this question is collecting and analyzing the records of what you own and what you owe and then applying a few accounting terms to the results:

- Your personal assets consist of what you own.

- Your personal liabilities are what you owe—your obligations to various creditors, big and small.

Preparing Your Net-Worth Statement

Your net worth (accounting term for your wealth) is the difference between your assets and your liabilities. Thus the formula for determining net worth is:

Assets − Liabilities = Net worth

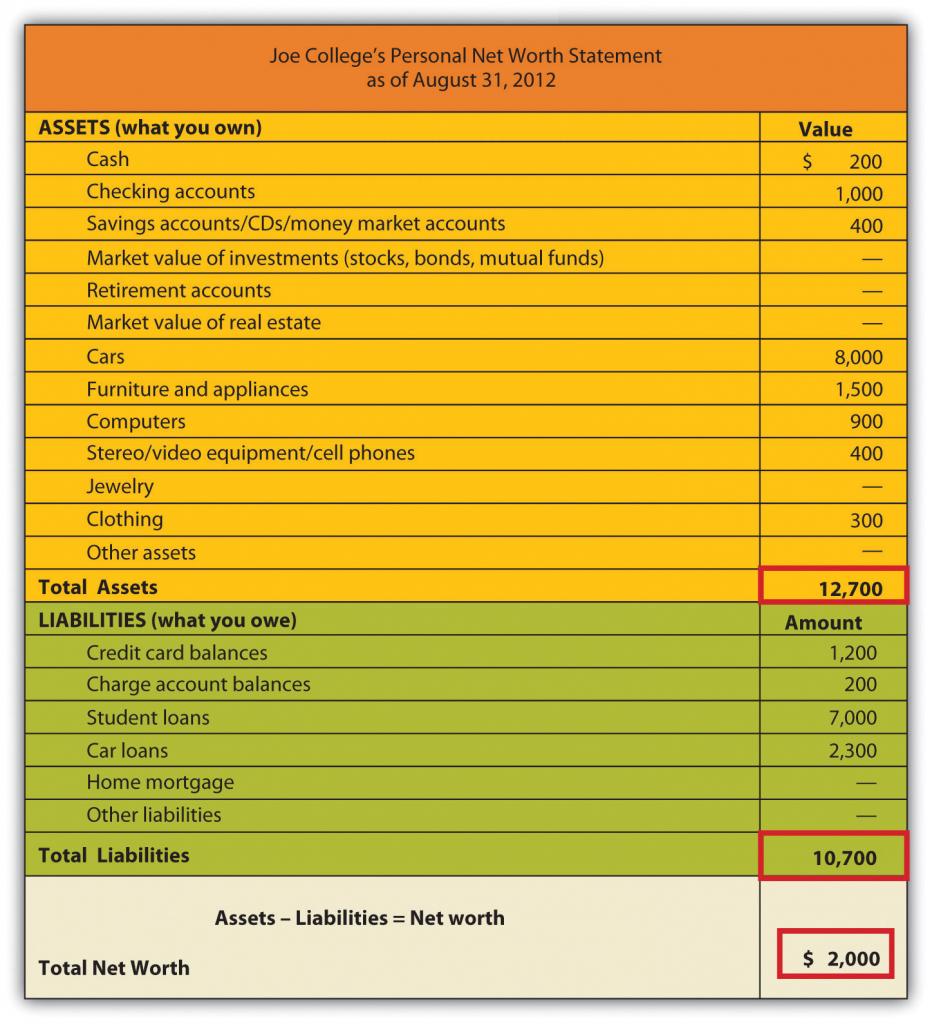

If you own more than you owe, your net worth will be positive; if you owe more than you own, it will be negative. To find out whether your net worth is on the plus or minus side, you can prepare a personal net worth statement like the one in Figure 12.6 “Net Worth Statement”, which we’ve drawn up for a fictional student named Joe College (Note that we’ve included lines for items that may be relevant to some people’s net worth statements but left them blank when they don’t apply to Joe).

Figure 14.6 Net Worth Statement

Assets

Joe has two types of assets:

- First are his monetary or liquid assets—his cash, the money in his checking accounts, and the value of any savings, CDs, and money market accounts. They’re called liquid because either they’re cash or they can readily be turned into cash.

- Everything else is a tangible asset—something that Joe can use, as opposed to an investment. (We haven’t given Joe any investments—such financial assets as stocks, bonds, or mutual funds—because people usually purchase these instruments to meet such long-term goals as buying a house or sending a child to college.)

Note that we’ve been careful to calculate Joe’s assets in terms of their fair market value—the price he could get by selling them at present, not the price he paid for them or the price that he could get at some future time.

Liabilities

Joe’s net worth statement also divides his liabilities into two categories:

- Anything that Joe owes on such items as his furniture and computer are current liabilities—debts that must be paid within one year. Much of this indebtedness no doubt ends up on Joe’s credit card balance, which is regarded as a current liability because he should pay it off within a year.

- By contrast, his car payments and student-loan payments are noncurrent liabilities—debt payments that extend for a period of more than one year. Joe is in no position to buy a house, but for most people, their mortgage is their most significant noncurrent liability.

Finally, note that Joe has positive net worth. At this point in the life of the average college student, positive net worth may be a little unusual. If you happen to have negative net worth right now, you’re technically insolvent, but remember that a major goal of getting a college degree is to enter the workforce with the best possible opportunity for generating enough wealth to reverse that situation.

Preparing Your Cash-Flow Statement

Now that you know something about your financial status on a given date, you need to know more about it over a period of time. This is the function of a cash-flow or income statement, which shows where your money has come from and where it’s slated to go.

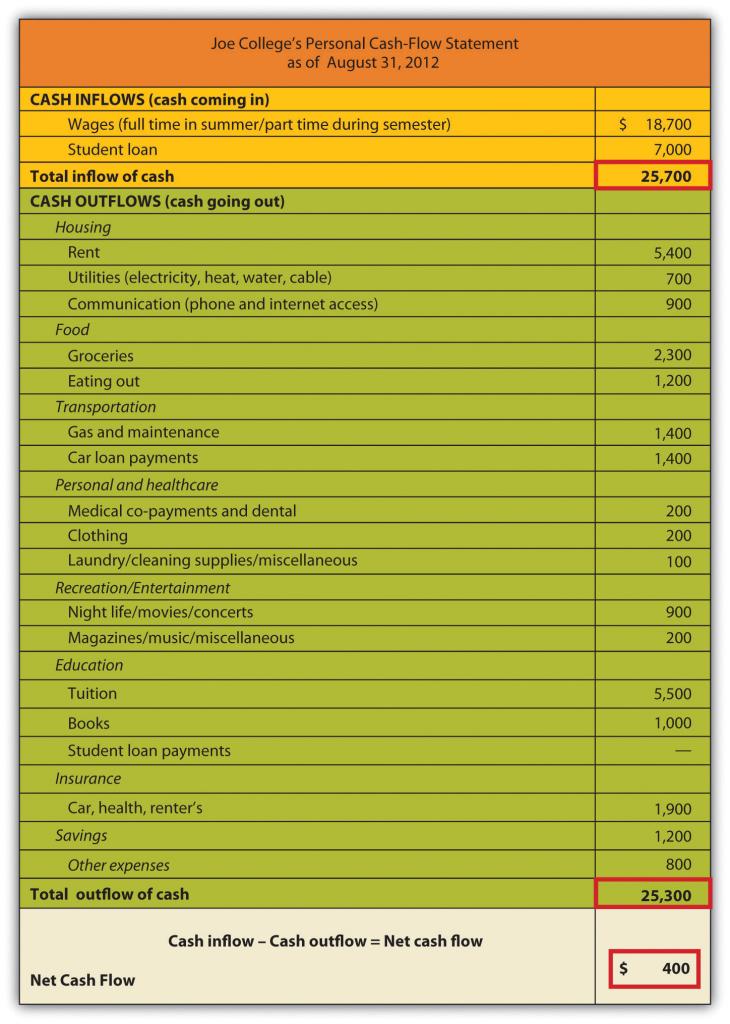

Figure 12.7 “Cash-Flow Statement” is Joe College’s cash-flow statement. As you can see, Joe’s income (his cash inflows—money coming in) is derived from two sources: student loans and income from a part-time job. His expenditures (cash outflows—money going out) fall into several categories: housing, food, transportation, personal and health care, recreation/entertainment, education, insurance, savings, and other expenses. To find out Joe’s net cash flow, we subtract his expenditures from his income:

$25,700 – $25,300 = $400

Figure 12.7 Cash-Flow Statement

Joe has been able to maintain a positive cash flow for the year ending August 31, 2012, but he’s cutting it close. Moreover, he’s in the black only because of the inflow from student loans—income that, as you’ll recall from his net worth statement, is also a noncurrent liability. We are, however, willing to give Joe the benefit of the doubt: Though he’s incurring the high costs of an education, he’s willing to commit himself to the debt (and, we’ll assume, to careful spending) because he regards education as an investment that will pay off in the future.

Remember that when constructing a cash-flow statement, you must record only income and expenditures that pertain to a given period, whether it be a month, a semester, or (as in Joe’s case) a year. Remember, too, that you must figure both inflows and outflows on a cash basis: you record income only when you receive money, and you record expenditures only when you pay out money. When, for example, Joe used his credit card to purchase his computer, he didn’t actually pay out any money. Each monthly payment on his credit card balance, however, is an outflow that must be recorded on his cash-flow statement (according to the type of expense—say, recreation/entertainment, food, transportation, and so on).

Your cash-flow statement, then, provides another perspective on your solvency: if you’re insolvent, it’s because you’re spending more than you’re earning. Ultimately, your net worth and cash-flow statements are most valuable when you use them together. While your net worth statement lets you know what you’re worth—how much wealth you have—your cash-flow statement lets you know precisely what effect your spending and saving habits are having on your wealth.

Step 2: Set Short-Term, Intermediate-Term, and Long-Term Financial Goals

We know from Joe’s cash-flow statement that, despite his limited income, he feels that he can save $1,200 a year. He knows, of course, that it makes sense to have some cash in reserve in case of emergencies (car repairs, medical needs, and so forth), but he also knows that by putting away some of his money (probably each week), he’s developing a habit that he’ll need if he hopes to reach his long-term financial goals.

Just what are Joe’s goals? We’ve summarized them in Figure 12.8 “Joe’s Goals”, where, as you can see, we’ve divided them into three time frames: short-term (less than two years), intermediate-term (two to five years), and long-term (more than five years). Though Joe is still in an early stage of his financial life cycle, he has identified and structured his goals fairly effectively. In particular, they satisfy four criteria of well-conceived goals: they’re realistic and measurable, and Joe has designated both definite time frames and specific courses of action.[42]

Figure 12.8 Joe’s Goals

| Short-term goals (less than 2 years) |

Intermediate-term goals (2-5 years) |

Long-term goals (more than 5 years) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

They’re also sensible. Joe sees no reason, for example, why he can’t pay off his car loan, credit card, and charge account balances within two years. Remember that, with no income other than student-loan money and wages from a part-time job, Joe has decided (rightly or wrongly) to use his credit cards to pay for much of his personal consumption (furniture, electronics equipment, and so forth). It won’t be an easy task to pay down these balances, so we’ll give him some credit (so to speak) for regarding them as important enough to include paying them among his short-term goals. After finishing college, he’ll splurge and take a month-long vacation. This might not be the best thing to do from a financial point of view, but he knows this could be his only opportunity to travel extensively. He is realistic in his classification of student loan repayment and the purchase of a home as long-term. But he might want to revisit his decision to classify saving for his retirement as a long-term goal. This is something we believe he should begin as soon as he starts working full-time.

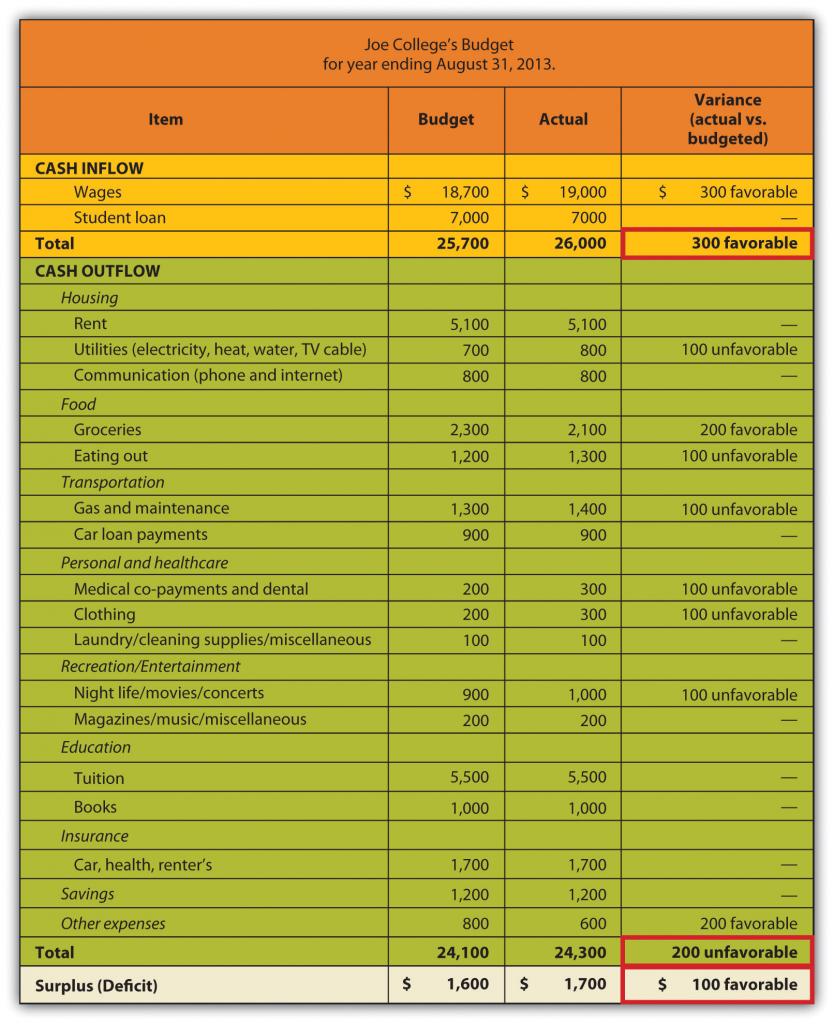

Step 3: Develop a Budget and Use It to Evaluate Financial Performance

Once he has reviewed his cash-flow statement, Joe has a much better idea of what cash flowed in for the year that ended August 31, 2012, and a much better idea of where it went when it flowed out. Now he can ask himself whether he’s satisfied with his annual inflow (income) and outflow (expenditures). If he’s anything like most people, he’ll want to make some changes—perhaps to increase his income, to cut back on his expenditures, or, if possible, both. The first step in making these changes is drawing up a personal budget—a document that itemizes the sources of his income and expenditures for the coming year, along with the relevant money amounts for each.

Having reviewed the figures on his cash-flow statement, Joe did in fact make a few decisions:

- Because he doesn’t want to jeopardize his grades by increasing his work hours, he’ll have to reconcile himself to just about the same wages for another year.

- He’ll need to apply for another $7,000 student loan.

- If he’s willing to cut his spending by $1,200, he can pay off his credit cards. Toward this end, he’s targeted the following expenditures for reduction: rent (get a cheaper apartment), phone costs (switch plans), auto insurance (take advantage of a “good-student” discount), and gasoline (pool rides or do a little more walking). Fortunately, his car loan will be paid off by midyear.

Revising his figures accordingly, Joe developed the budget in Figure 12.9 “Joe’s Budget” for the year ending August 31, 2013. Look first at the column headed “Budget.” If things go as planned, Joe expects a cash surplus of $1,600 by the end of the year—enough to pay off his credit card debt and leave him with an extra $400.

Figure 12.9 Joe’s Budget

Figuring the Variance

Now we can examine the two remaining columns in Joe’s budget. Throughout the year, Joe will keep track of his actual income and actual expenditures and will enter the totals in the column labeled “Actual.” Like most reasonable people, however, Joe doesn’t really expect his actual figures to match with his budgeted figures. So whenever there’s a difference between an amount in his “Budget” column and the corresponding amount in his “Actual” column, Joe records the difference, whether plus or minus, as a variance. Two types of variances appear in Joe’s budget:

-

Income variance. When actual income turns out to be higher than expected or budgeted income, Joe records the variance as “favorable.” (This makes sense, as you’d find it favorable if you earned more income than expected.) When it’s just the opposite, he records the variance as “unfavorable.”

-

Expense variance. When the actual amount of an expenditure is more than he had budgeted for, he records it as an “unfavorable” variance. (This also makes sense, as you’d find it unfavorable if you spent more than the budgeted amount.) When the actual amount is less than budgeted, he records it as a “favorable” variance.

Setting Mature Goals

Before we leave the subject of the financial-planning process, let’s revisit the topic of Joe’s goals. Another look at Figure 12.8 “Joe’s Goals” reminds us that, at the current stage of his financial life cycle, Joe has set fairly simple goals. We know, for example, that Joe wants to buy a home, but when does he want to take this major financial step? And of course, Joe wants to retire, but what kind of lifestyle does he want in retirement? Does he expect, like most people, a retirement lifestyle that’s more or less comparable to that of his peak earning years? Will he be able to afford both the cost of a comfortable retirement and, say, the cost of sending his children to college? As Joe and his financial circumstances mature, he’ll have to express these goals (and a few others) in more specific terms.

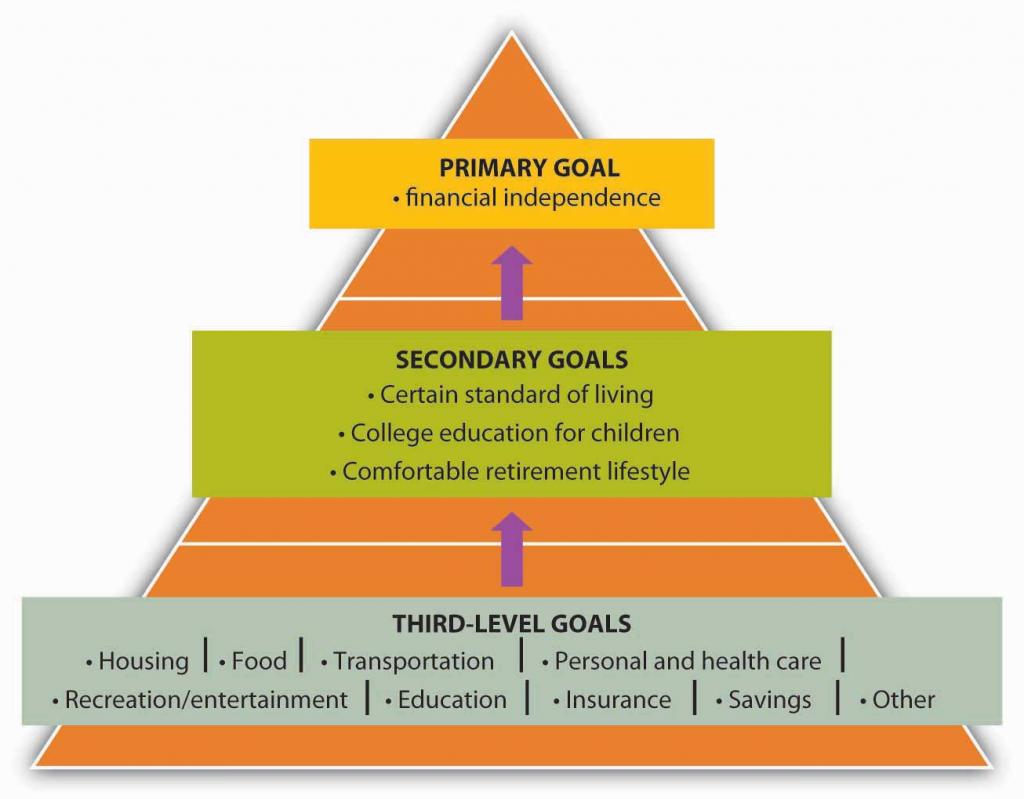

Levels of Mature Goals

Let’s fast-forward a decade or so, when Joe’s picture of stages 2 and 3 of his financial life cycle have come into clearer focus. If he hasn’t done so already, Joe is now ready to identify a primary goal to guide him in identifying and meeting all his other goals.[43] Suppose that because Joe’s investment in a college education has paid off the way he’d planned ten years ago, he’s in a position to target a primary goal of financial independence—by which he means a certain financially secure life not only for himself but for his children, as well. Now that he’s set this primary goal, he can identify a more specific set of goals—say, the following:

- A standard of living that reflects a certain level of comfort—a level associated with the possession of certain assets, both tangible and intangible.

- The ability to provide his children with college educations.

- A retirement lifestyle comparable to that of his peak earning years.

Having set this secondary level of goals, Joe’s now ready to make specific plans for reaching them. As we’ve already seen, Joe understands that plans are far more likely to work out when they’re focused on specific goals. His next step, therefore, is to determine the goals on which he should focus this next level of plans.

As it turns out, Joe already knows what these goals are, because he’s been setting the appropriate goals every year since he drew up the cash-flow statement in Figure 12.7 “Cash-Flow Statement”. In drawing up that statement, Joe was careful to create several line items to identify his various expenditures: housing, food, transportation, personal and health care, recreation/entertainment, education, insurance, savings, and other expenses. When we introduced these items, we pointed out that each one represents a cash outflow—something for which Joe expected to pay. They are, in other words, things that Joe intends to buy or, in the language of economics, consume. As such, we can characterize them as consumption goals. These “purchases”—what Joe wants in such areas as housing, insurance coverage, recreation/entertainment, and so forth—make specific his secondary goals and are therefore his third-level goals.

Figure 12.10 “Three-Level Goals/Plans” gives us a full picture of Joe’s three-level hierarchy of goals.

Figure 12.10 Three-Level Goals/Plans

Present and Future Consumption Goals

A closer look at the list of Joe’s consumption goals reveals that they fall into two categories:

- We can call the first category present goals because each item is intended to meet Joe’s present needs and those (we’ll now assume) of his family—housing, health care coverage, and so forth. They must be paid for as Joe and his family take possession of them—that is, when they use or consume them. All these things are also necessary to meet the first of Joe’s secondary goals—a certain standard of living.

- The items in the second category of Joe’s consumption goals are aimed at meeting his other two secondary goals: sending his children to college and retiring with a comfortable lifestyle. He won’t take possession of these purchases until sometime in the future, but (as is so often the case) there’s a catch: they must be paid for out of current income.

A Few Words about Saving

Joe’s desire to meet this second category of consumption goals—future goals such as education for his kids and a comfortable retirement for himself and his wife—accounts for the appearance on his list of the one item that, at first glance, may seem misclassified among all the others: namely, savings.

Paying Yourself First

It’s tempting to glance at Joe’s budget and cash-flow statement and assume that he shares with most of us a common attitude toward saving money: when you’re done allotting money for various spending needs, you can decide what to do with what’s left over—save it or spend it. In reality, however, Joe’s budgeting reflects an entirely different approach. When he made up the budget in Figure 12.9 “Joe’s Budget”, Joe started out with the decision to save $1,600—or at least to avoid spending it. Why? Because he had a goal: to be free of credit card debt. To meet this goal, he planned to use $1,200 of his current income to pay off what would continue to hang over his head as a future expense (his credit card debt). In addition, he planned to have $400 left over after he’d paid his credit card balance. Why? Because he had still longer-term goals, and he intended to get started on them early—as soon as he finished college. Thus his intention from the outset was to put $400 into savings.