Section 2 : Southern Door ~ Learning with Open Heart and Mind

Chapter 7: Trauma and Intergenerational Trauma ~ Traditional Healing ~ Contemporary Health, Healing, and Wellness

Introduction

I wish to introduce this chapter with the following statement, taken from my course syllabus. And although I spoke to this at the beginning of our journey, it is worth repeating again.

“The history of Indigenous peoples is one that is characterized by trauma. While we are attempting to move into a period of healing and reconciliation, trauma and its impacts are still with us. Students will be exposed to this topic in our readings, class discussions, personal stories, and exercises. This needs to be stated, as one does not want to be taken ‘off guard.’ Having said this, we have many resources at our disposal, including Elders, experienced counsellors, and caring instructors who have experience in navigating these difficult topics” (IKE-1040 Course Outline, 2024).

Topics at a Glance

- What is Trauma?

- Intergenerational Trauma

- Traditional Healing

- Contemporary Health, Healing, and Wellness

What is Trauma?

One of the first comprehensive writings on historical trauma and Indigenous peoples was prepared by Cynthia C. Wesley-Esquimaux and Magdalena Smolewski for the Aboriginal Healing Foundation Research Series. Wesley-Esquimaux and Smolewski (2004) in Historic Trauma and Aboriginal Healing write,

“Historic trauma became a part of Aboriginal people’s common experience, covertly shaping individual lives and futures, and devastating entire communities and regions. Since contact, First Nation people have experienced several waves of traumatic experience on social and individual levels that have continued to place enormous strain on the fabric of Aboriginal societies across the continent. Throughout this report, the term ‘genocide’ is used many times when referring to the Aboriginal people’s experiences in America. Since psychologists, psychiatrists, and anthropologists all agree that victims of intense trauma, as well as their offspring, show the same emotional responses as the survivors of genocide, it is necessary to address this issue, anticipating possible controversy over the use of the term “genocide” in the Aboriginal context. Recently, more and more socio-cultural researchers and historians venture into this delicate area of study, pointing out that the Aboriginal civilization witnessed many “unknown” or “silent” genocides that often left various cultural groups badly damaged and even extinct (such was the case with the Aboriginal population of Tasmania). More researchers dare to use the term genocide; whereas before, people talked about oppression, relocations, stolen generations, and so on, and risking a strong critique from their more conservative colleagues. This report sees the necessity of discussing issues of genocide in a public and/or academic arena. This part of the study is intended to initiate a discussion and illustrate the contention that Aboriginal people in the Americas, throughout the centuries, had to deal with strong, relentless forces of annihilation that were as evil and destructive as the Nazi’s power was during World War II. It is only due to their cultural strength that some Aboriginal people survived to pass painful memories onto the generations after. Again, Aboriginal people’s experiences were not particular in the world history of oppression.

It has been pointed out that historic colonialism produced a profound alteration in the socio-cultural milieu of all subjugated societies, but Aboriginal people in North America do not stand alone in the annals of historical injustice. Glaring examples include the forced relocations of Indigenous people in South Africa, slavery on the African continent and the stolen generations of Indigenous people in Australia. Terrifying examples of oppressive tendencies in other historical contexts include the Jewish Holocaust and the internment of Japanese nationals in Canada. A few examples of societies and cultures affected by visible genocide were presented. However, the reader should note that there were many others” (Wesley-Esquimaux and Smolewski, 2004, pp. 55-56).

The authors also explain the clinical disorder known as Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder below:

“1. A history of subjugation to totalitarian control over a prolonged period [of time] (months to years). Examples include hostages, prisoners of war, concentration camp survivors, and survivors of some religious cults. Examples also include those subjected to totalitarian systems in sexual and domestic life, including survivors of domestic battering, childhood physical or sexual abuse, and organized sexual exploitation (Herman, 1997:121).

2. Alterations in affect regulation, including:

- persistent dysphoria;

- chronic suicidal preoccupation;

- self-injury;

- explosive or extremely inhibited anger (may alternate); [and]

- compulsive or extremely inhibited sexuality (may alternate).

3. Alterations in consciousness, including:

- amnesia or hyperamnesia [sic] for traumatic events;

- transient dissociative episodes;

- depersonalization/derealization; [and]

- reliving experiences, either in the form of intrusive post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms or in the form of ruminative preoccupation.

4. Alterations in self-perception, including:

- sense of helplessness or paralysis of initiative;

- shame, guilt, and self-blame;

- sense of defilement or stigma; [and]

- sense of complete difference from others (may include sense of specialness, utter aloneness, belief no other person can understand, or non-human identity).

5. Alterations in perception of perpetrator, including:

- pre-occupation with relationship with perpetrator (includes preoccupation with revenge);

- unrealistic attribution of total power to perpetrator (caution: victim’s assessment of power realities may be more realistic than clinician’s);

- idealization or paradoxical [relationship]…

- sense of special or supernatural relationship; [and]

- acceptance of belief system or rationalizations of perpetrator.

6. Alterations in relations with others, including:

- isolation and withdrawal;

- disruption in intimate relationships;

- repeated search for rescuer (may alternate with isolation and withdrawal);

- persistent distrust; [and]

- repeated failures of self-protection.

7. Alterations in systems of meaning, [including]:

- loss of sustaining faith; [and]

- sense of hopelessness and despair” (Wesley-Esquimaux and Smolewski, 2004, p. 95).

A copy of the authors’ full report can be obtained at https://www.ahf.ca/files/historic-trauma.pdf.

Further resources on trauma from the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, also part of the Research Series mentioned earlier, include reports also examining Métis and Inuit experiences:

Reclaiming Connections: Understanding Residential School Trauma Among Aboriginal People

Métis History and Experience and Residential Schools in Canada

A Brief Report of the Federal Government of Canada’s Residential School System for Inuit

The Aboriginal Healing Foundation ceased operations in 2014, as funding was no longer available; however, their contribution to healing and community health was monumental. I invite you to visit their website, which contains a record of their work — and their story.

Intergenerational Trauma

Let us now view a couple of videos that present on Intergenerational Trauma. Please bear in mind the difficult and potentially ‘triggering’ material, not only in this chapter, but throughout the textbook.

Intergenerational Trauma Animation

- What did you take away from this viewing?

- Did anyone note where this animation was produced? What does that mean?

- After viewing, what other thoughts occurred after you had time to reflect?

The Impact of Intergenerational Trauma

- What did you take away from this viewing?

- What does this tell you about the impacts of historic and intergenerational trauma?

- What are the costs of intergenerational trauma?

- Does our knowledge of impacts and costs suggest we need to pay attention to current-day actions and harms?

It is through the work of the Aboriginal Healing Foundation that created the conditions for Indigenous peoples to be directly engaged in their own healing. You can read about their research and approaches, which were ground-breaking for positioning traditional healing through culture into practice across Canada, on reserves, in urban settings, and even in Canada’s prisons.

Traditional Healing

I would now like to present on a study that I was engaged in as a federal government public servant with Correctional Services Canada between 2003 and 2014, and even beyond.

I will begin by telling my story of how I became involved in the development of the Aboriginal Offender Substance Abuse Program for Correctional Services Canada in 2003. The written record can be found in the CSC Research Report by Kunic & Varis (2009). The need was very clear and aptly stated by CSC Elder Susan Stranglingwolf, Siksika First Nation, AB: “Our boys need this program so they can return to their communities healthy and strong. You will make mistakes and that is okay. As long as you do what needs to be done in a good and respectful way.” In the latter part of her statement, Elder Susan was referring to the fact that the work on which we were about to embark was historic and never done before. When doing this work, one has to be patient and know that there will be trial and error and lessons learned; but the key was to be guided by Indigenous teachings and values.

But before I begin, I’d like to draw attention to several photos from the experience; firstly, the place at which the journey began can be seen in Figure 26; next, Figure 27 shows the team of Elders, Knowledge Keepers, and CSC Directors who were instrumental in its launch; and lastly, the final national training session in Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory, Ontario is shown in Figure 28. Everything came together in the Fall of 2003 at the Willow Cree Healing Lodge, located on the Beardy’s and Okemasis First Nation’s Reserve, just west of Duck Lake, Saskatchewan.

Figure 26

Willow Cree Healing Lodge, Saskatchewan

Figure 27

2003 AOSAP Project Team, Wanuskewin, SK

Figure 28

AOSAP National Training, Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory, ON

A review of the literature on programmed development was clear on what was considered as the best approach to providing effective treatment for Indigenous peoples — and in particular — Indigenous offenders. I present a synopsis of what we found from this review.

“It has been shown that the integration of contemporary best practices with culturally appropriate approaches (i.e., a blended approach) promotes healing and general wellbeing among Aboriginal offenders, and reinforces cultural values, which may later serve to mitigate risk for re-offending and sustain healthy community functioning (Ellerby & Ellerby, 2000; Trevethan, Moore & Allegri, 2005).

A blended approach recognizes that addressing family of origin and developmental experiences, and teaching traditional culture are critical to the process of healing and maintaining wellness of Aboriginal peoples (Ellerby & Ellerby, 2000; Ellerby, 2002). It is generally accepted that for western therapies and models to be most effective with Aboriginal peoples, they must examine Aboriginal spirituality, incorporate traditional Aboriginal thinking and practice and understand the Aboriginal worldview (Duran & Duran, 1995; Dell & Lyons, 2007). Aboriginal scholars have consistently maintained that the role of traditional teachings and culture in the facilitation of wellness for, and resiliency of Aboriginal peoples must be regarded as the foundation on which treatment is grounded (Couture, 2000)” (Kunic & Varis, 2009).

You may recall in Chapter 3, we spoke about Indigenous worldviews and ways of knowing, being, and doing. Without sounding facetious, Indigenous peoples know how to live, heal, survive, and thrive. Indigenous peoples have been doing it for millennia, even though they were destined for extinction, not through a catastrophic disaster like an asteroid striking the earth, but a more treacherous and prolonged force — colonization.

When Dr. Joe, my mentor, helped us conceptualize the program, his recommendation was absolutely clear. He spoke of the concept of a blended approach, and, as mentioned earlier, he used the term “using medicines on both sides of the river,” which signified using the “best practices of both worlds.”

The significance of using the “best practices of both worlds” was that the substance abuse treatment (healing program), which was developed by our team at the Addictions Research Centre, Correctional Services Canada, Montague, PEI, was that it was highly successful — not anecdotally — but as evidenced through research.

We first piloted the program in several institutions across the country, one location being the Stony Mountain Institution, in my homeland, Territory 1, just north of where I grew up in Winnipeg, Manitoba. This can be seen in Figure 29.

Figure 29

CCS’s Stony Mountain Institution, Manitoba

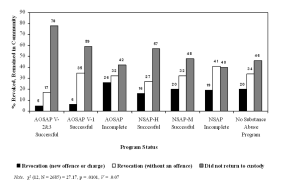

Below in Figure 30, we see the results from our study. These capture that offenders who successfully completed the AOSAP had much better outcomes after being conditionally released and remaining in the community, without a revocation and/or criminal conviction, compared to participants in a main-stream program (NSAP) or participants who had not completed any form of treatment.

Figure 30

Distribution of Revocations Across Program Exposure Categories

“These findings add weight to the evidence in support of traditional approaches to treating substance abuse problems in Aboriginal men.

Aboriginal scholars have consistently argued that the role of traditional teachings and culture in the facilitation of wellness for, and resiliency of Aboriginal peoples must be regarded as the foundation on which treatment is grounded. The fact that AOSAP outperformed mainstream substance abuse programs is consistent with contemporary best practices in effective correctional intervention. Offering content and a mode of service delivery that is responsive to the offender’s attributes will facilitate active participation and engagement of the offender in treatment and lead to better outcomes.

In the case of Aboriginal offenders, programs and interventions that are grounded in Aboriginal traditions, spirituality, and culture that strive to heal the individual in holistic terms, will facilitate rehabilitation efforts and enhance engagement and participation of the offender in treatment” (Kunic & Varis, 2009).

This research is just one perspective; another perspective is the actual men who participated in the program: let us hear what they had to say.

Voices from Inside – How Culture Healed

Contemporary Health, Healing, and Wellness

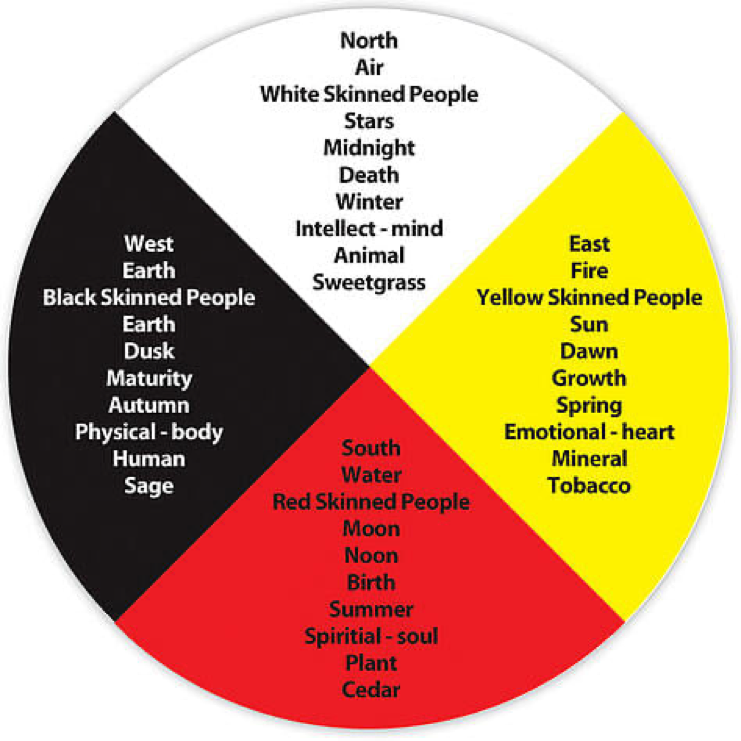

Many contemporary Indigenous health, healing, and wellness programs use cultural teachings as their foundation, most often delivered through an Elder. One such teaching is the Medicine Wheel depicted in Figure 31. While it is not the only method or tool, it has found great utility.

Figure 31

The Medicine Wheel

There are a number of ways that the Medicine Wheel teachings are used by Elders, practitioners, and communities. They may be integrated into treatment, and, dependent on the cultural teachings, those in the traditional healing or helping professions may introduce participants to the cultural teachings respecting the connectedness of relations that comprise the world in which they live, as depicted in the image above.

Introduced in the AOSAP, the Medicine Wheel, which we renamed the Circle of Wellness, unfolded into other explorations, including how it applied to the four domains of self (physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual), stages and roles in life, and how it could help with self-care, wellness, healthy living, and self-monitoring. There are many uses of the Medicine Wheel, including community development, research, and education. If you want more information regarding the teachings contained in the Medicine Wheel, please see Special Topics of Interest at the end of the chapter.

Lastly, contemporary traditional healing and medicine can be found in an array of settings, encompassing varied approaches and methods. On a most positive note, this upsurge in cultural reclamation and self-autonomy are attracting more and more Indigenous youth to enter professions like healthcare. Before leaving this topic, let us first look at one community site using traditional healing.

Like most topics covered throughout this text, we cannot examine these in any depth in an introductory course, such as Indigenous Teachings of Turtle Island. The Special Topics of Interest and Cultural Competency Supplemental Tutorials at the end of each chapter are offered as additional resources, should you wish to explore further. Moreover, the Indigenous Studies Program exists so you can enter higher-level courses to examine topics of interest in more detail.

Key Terms and Concepts from the Chapter

- complex post-traumatic stress disorder

- Aboriginal Healing Foundation

- intergenerational trauma

- a blended approach

- using medicines on both sides of the river

- health

- healing

- wellness

- the Medicine Wheel/Circle of Wellness

- Alfred, Venne, and Manuel articles – A Manual for Decolonization (pp. 10-21)

Special Topics of Interest

Cultural Competency Supplemental Tutorials