Identity

Sounds Queer: Linguistic Perceptions of Sexual Orientation and Gender

Keridwen B Campbell

Sounds Queer: Linguistic Perceptions of Sexual Orientation and Gender

by Keridwen B. Campbell

The search term “gay voice” (quotations included) brings up ~164,000 results on Google, ranging from academic articles to opinion pieces, from government websites to people asking questions on Quora.com. Clearly, whatever the “gay voice” is, it is not a phenomenon relegated to the consciousness of queer people but something many people are aware of and curious about. As sociolinguist Erez Levon notes, “there is a popular belief that speech is a reliable marker of an individual’s sexuality, and linguists have long been interested in identifying the particular acoustic features that cue such perceptions” (2014, p. 541). The so-called “gay voice” as it relates to gay cisgender men has been increasingly researched in recent decades, but the amount of research into the voices of cisgender lesbians, bisexual people of various genders, and transgender people of various sexual orientations has grown as well. This paper will touch on the idea of a “gay voice” for various constructed orientation categories — from both physiological and psychosocial perspectives — as well as how a “gay voice” is linguistically constructed and perceived by listeners. Rather than an immutable feature of queer identity, the “gay voice” is fluid and dependent on interpersonal identities and the larger social milieu; I argue that gender inversion theory does not fully capture this understanding.

Sedivy (2020) describes the tendency for listeners to make split-second assumptions about speakers based on auditory features such as accents and dialects. While accents are usually associated with region or socioeconomic class, the same process can be applied to the various ways queer people might speak differently than their non-queer majority counterparts. Stereotypes that inform the listener as to the identity of the speaker can be critical in terms of actually processing auditory linguistic input, as some acoustic features of speech may be closely tied to the identity of a given speaker; these cues can vary wildly between identity categories, gender included (Sedivy, 2020). For example, the F1 frequencies of /s/ and / ʃ/ (like shop) tend to vary significantly between men and women (Sedivy, 2020; Tripp & Munson, 2021). Thus, “if listeners are optimally sensitive to the structure inherent in speech, they should pay attention to certain aspects of a talker’s identity when interpreting some cues” (Sedivy, 2020, pp. 280-281) However, such perceptions can also lead to the stigmatization of certain speech patterns and discrimination against the people who exhibit those patterns (Fasoli et al., 2021). For example, one study found that participants were less likely to evaluate gay men as hireable and assigned lower salaries to gay than to heterosexual candidates, but this was only true when participants made their evaluations based on the candidates’ voices — there were no significant differences when participants made evaluations based on the candidates’ faces (Fasoli et al., 2017). By analyzing the linguistic features often associated with queer identity, we can better understand attitudes and perceptions of queerness.

“[I]t is linguists in particular who can . . . broaden the scope of investigation by looking at queer people’s phonology, syntax, semantics, pragmatics, and discourse structures.” (Gaudio, 1994, p. 31)

Gender inversion theory, which has Freudian origins, is intertwined with long-standing stereotypes of queerness, in which queer members of one sex will exhibit behaviours more similar to that of heterosexual members of the opposite sex (Kachel et al., 2018; Kite & Deaux, 1987), and this has informed many psycholinguistic inquiries into the gay voice (Kachel et al., 2018; Daniele et al., 2020). Importantly, gender inversion theory is not relegated to the domain of speech and speech perception. However, for the purposes of this paper, non-linguistic aspects of the theory are largely irrelevant.

An article by Rendall et al. (2008) offers a variation of gender inversion theory with a biosocial hypothesis, in which the distinctive features of gay speech can be viewed as incidental products of broader behavioural distinctions between gay and straight people, arising from the biological traits of homosexuality. This differs from sociocultural framings of gender inversion theory, which stress the selective and sometimes purposeful uptake of certain speech features to signal part of their identity (Gratton, 2016; Kite & Deaux, 1987; Rendall et al., 2008). “It’s no secret among ethnographers that people often tailor their appearance and consumption habits in a way that signals their identification with a certain social group or ideology. The same seems to be true of accents” (Sedivy, 2020, p. 276). Their study, which included men and women of both heterosexual and bi/homosexual orientations in southern Alberta, measured the height and weight of participants as well as voice-acoustic variations. Results indicated overall non-significant body size variation between same-gender groups (although gay men were significantly shorter than straight men on average (p = <0.01)); within the voice-acoustic measures, they hypothesized a correlation between body size, sexual orientation, and pitch, but pitch was also not a significant indicator of sexual orientation (Rendall et al., 2008). However, they did observe significant differences in formant frequencies of certain vowels. In regard to gender inversion theory, they note that results across current literature “do not yet fully endorse the stereotypes but they do not entirely discount them either; nor do they cleanly favor any single mechanistic hypothesis” (Rendall et al., 2008, p. 188). Although gender inversion theory fails to account for the robust psycholinguistic factors at play, the theory persists, and the idea that sexual orientation can be detected phonetically remains a compelling one across cultures.

The Issue of Gender

Gender can be defined as the behavioural, psychological, social, and cultural traits typically associated with one biological sex group (Merriam-Webster, 2019). Gender nonconformity, then, is an outward expression of gender that defies the typical norms associated with the gender one identifies with (Merriam-Webster, 2023; White, 2020). Queer communities may be disproportionately gender nonconforming (Kachel et al., 2020) — and the argument could be made that homosexuality is an inherently gender nonconformist trait since traditional Western gender roles assume heterosexual partnership (heteronormativity). Where does sexual orientation fit into the picture? This question is surprisingly difficult to answer and poses many problems when researching the gay voice and auditory gaydar. Fundamental questions must be asked to remain aware of potential biases in researching queer populations. Whom do we include in our sample? What are we trying to predict? How do we define “gay”, “lesbian”, “bisexual,” “queer”, et cetera? With a broad overview of relevant literature, it becomes evident that there are very few consistencies in the results across studies, save for the fact that differences are (often but not always) there and may be studied.

It is common knowledge that men have lower voices than women, statistically. This is due to physiological differences spurred by estrogen- versus testosterone-dominant puberties, in which the latter spurs a lengthening of the vocal tract (Listen Lab, 2020). Although some arguments have been made as to correlations between overall body size (see Rendall et al., 2008), sex hormones have a much greater impact on vocal pitch in humans than height or weight, and the voice of a 6’2” woman is still likely to be higher than the voice of a 5’2” man (Listen Lab, 2020). However, the correlation between vocal tract length and body size is relatively stable in women as compared to men, whose body sizes do not systematically correlate with the sizes of their vocal tracts; further, gender differences in voice resonance are statistically disproportionate to the average difference in vocal tract shape and length between men and women (Listen Lab, 2020). As Sedivy (2020) says, “language is the result of an intricate collaboration between biology and culture. It’s extremely unlikely that all of the features of language are genetically determined, or conversely, that all of them are cultural “inventions” (p. 46). Many gendered patterns of speech and vocal production are acquired in childhood — well before puberty spurs physiological differences in the vocal tract—sometimes as young as three or four years old (Zimman, 2017).

[I]n becoming linguistically competent, the child learns to be a fully fledged male or female member of the speech community; conversely, when children adopt linguistic behaviour considered appropriate to their sex, they perpetuate the social order which creates gender distinctions. (Coates, 1968, p. 121)

We also know that gender is phonetically indexed in differing ways depending on the language, culture, and individual (Zimman, 2017) and may overlap with other social identity categories such as class (Gratton, 2016) and, of course, sexual orientation. Additionally, Tripp & Munson (2021) stress the role of heteronormativity and gender sexuality entanglement in psycholinguistic perception, claiming that “perceptual systems for social categories demonstrably rely on interdependent cognitive processes” (p. 1). Gratton (2016), researching the speech of nonbinary participants from a Toronto queer community, calls on us to consider that “gender identity . . . is not something that exists prediscursively but rather individuals construct through linguistic and other kinds of semiotic practices” (p. 52). Although young children may pick up on gendered language patterns unconsciously, there is ample evidence that adults and older youth engage in metalinguistic practices, consciously changing aspects of their speech depending on the context, and this may be due to a variety of reasons including signalling one’s position as a member of a particular in-group or obscuring that position (Daniele et al., 2020; Gratton, 2016). There is very little reason to believe that the gay voice would differ from gender in terms of being constructed as an element of sexual orientation identity, rather than an inflexible trait as suggested by Rendall et al. (2008). Gender inversion theory does not inherently dispute this view.

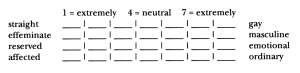

One of the earliest major undertakings in queer linguistics, a study by Rudolf Gaudio (1994) examined what he then described as the “oft-repeated . . . yet largely unexplored” (p. 31) stereotype that the voices of gay men should be effeminate. In congruence with gender inversion theory, he hypothesized that they would exhibit both higher pitch and greater pitch variation than straight men. He did this by analyzing the speech of four openly gay men and four straight men from the San Francisco Bay Area, each of whom was asked to read various non-fiction and fiction passages ranging in emotionality in addition to a recorded interview with the researcher. The audio from these was spliced into 16 clips, which were rated by undergraduate students using a set of Likert scales according to the features Gaudio identified as being stereotypical of the gay male voice (see Figure 1).

Surprisingly, although the raters’ guesses about sexual orientation were generally accurate, there were no significant findings in relation to the speakers’ pitch or pitch variation (Gaudio, 1994) — perhaps due to linguistic accommodation on the part of straight speakers in a densely queer part of the U.S. (Law, 2016), or perhaps due to inaccuracies in the measures taken to index sexual orientation in the study. While the gay voice is no longer unexplored territory by any means, Gaudio’s early work remains influential in the sphere of queer linguistic studies and goes to show gender inversion theory’s long-lasting hold on perceptions of queer voices.

Figure 1

Rating Scale from Gaudio (1994)

Queer-Sounding Qualities

As I noted in the previous section, Gaudio’s (1994) work sought to investigate stereotypical features of the gay voice, including pitch and pitch variation. However, pitch is not the only feature associated with sounding queer. Just as gender is indexed differently according to language and culture (Zimman, 2017), so is sexual orientation — and as I will illustrate, sexual orientation is also indexed differently according to gender, sometimes in alignment with gender inversion theory, and sometimes not. In this section, I will describe various features associated with queer voices.

The Gay Voice

When most people think of “the gay voice”, it is that of a white (likely cisgender) man from psychology’s favourite WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrial, Rich, Democratic) population. That may be for a good reason; unsurprisingly, these particular iterations of the gay voice are most well-defined and replicated across psycholinguistics research. In addition to higher global pitch and fundamental frequencies (Law, 2016), linguists have observed: a more negative spectral skew of /s/ (Munson et al., 2006; Willis, 2021); longer /s/ duration (Linville, 1998); higher peak frequencies of /s/ (Law, 2016; Linville, 1998); higher F1 frequencies on some vowels including /ε/ (like bed), /æ/ (like cat) (Munson et al., 2006; Rendall et al., 2008), and /a/ (Sulpizio et al., 2015); higher F2 frequencies on some vowels including /u/ (Munson et al., 2006), /ε/, /a/ and /I/ (Sulpizio et al., 2015); lower F1, F2, and F4 frequency of the /ə/ vowel (Rendall et al., 2008); and increased /s/-fronting (Van Borsel et al., 2009), which is a surprisingly popular stereotype. Other features commonly associated with the gay voice are nasality, especially for German speakers/listeners (Kachel et al., 2018), and longer vowel duration, especially for Italian speakers/listeners (Sulpizio et al., 2015). Despite strong stereotypes, the results of psycholinguistic studies are often conflicting and vary based on region, culture, and language.

The Lesbian Lexicon

When it comes to lesbian language, the results are even less clear than for gay men, and gender inversion theory seems to fall short of any explanation. As stated above, replications in the gay voice of white men are not uncommon, and gay male culture has usually been given more attention, though not necessarily for poor reasons. As Gaudio explained in his work:

My focus is on openly gay male speakers in particular. The exclusion of women is principled: lesbians and bisexual women constitute communities that are in many ways distinct from, though often allied with, those of queer men. To treat male and female speech under the single rubric gay would inevitably lead to a privileging of certain (almost always male) speech communities over others. (Gaudio, 1994, p. 31)

A similar study to Gaudio’s (1994) was undertaken with lesbians in the same area of America several years later with similarly vague results (Waksler, 2001). Gender inversion theory predicts that lesbian women will have speech patterns and features more similar to those of heterosexual men than to heterosexual women. More often than not, linguistic studies of gay women come up with no significant differences between the speech of lesbians versus straight women at all (Kachel et al., 2017; Moonwomon, 1985; Sulpizio et al., 2019).

Overall, it seems that differences in lesbian speech may differ more so lexically than phonetically (Queen, 1997) For example, lesbian communities — notably discrete from gay male communities in many parts of Canada and the U.S., as noted by Gaudio (1994) — have in recent history been associated with radical politics and thus may be associated with a unique vocabulary. In a guest chapter of the influential queer linguistics book, Queerly Phrased (Hall & Livia, 1997), Robin Queen writes a methodical review of several lesbian comics in an attempt to understand lesbian speech.

The characters are all created by lesbians for a predominantly lesbian audience, and thus the characters’ believability relies on social knowledge that is assumed to be shared. They are characters who are politically and socially positioned within a larger context that includes elements specific to lesbians, specific to women, specific to queers, and specific to a full range of groups marginalized on the basis of their ethnicity, their socioeconomic status, and/or their political beliefs. (Queen, 1997, pp. 223-224)

These representations of lesbian speech are not necessarily accurate to how lesbians talk, as Queen acknowledges, but it does give some insight that is lacking in more contemporary psycholinguistic research. The author more readily acknowledges the relativity of the term “lesbian” than contemporary researchers (see: Kachel et al., 2017; Sulpizio et al., 2019), cautioning readers of the differences between externally imposed definitions of lesbianism, which can be problematic and exclusionary, versus the experiences of lesbians within queer communities. Thus, “one of the problems with previous research on the language of lesbians may have been the result of the ways in which the researchers imagined the lesbian speech community” (Queen, 1997, pp. 237-238). Queen goes on to explain various stereotypes of lesbian language that may or may not be supported by linguistic research: cursing; use of [in] or [en] as opposed to the more “proper” [iŋ]; postvocalic /r/ deletion; “flat” intonation; contracted verb forms; and purposely inflammatory expressions, especially regarding (their) male anatomy (Queen, 1997).

Interestingly, an ethnographic study by Levon (2009, 2010) found that Israeli lesbian (and gay) activist groups were more likely to display a greater range of stereotyped and pitch-related variance when discussing queer-related topics as compared to other topics of discussion. However, the difference was far greater for members of more liberal or mainstream groups than for members of radical groups; the radical groups had more consistent phonetic properties of speech across all topics, suggesting a lesser degree of identity compartmentalization (Levon, 2010). Regarding the motives of the ethnography, Levon notes:

[M]y goal is not to describe a representative “gay-” or “lesbian-Israeli” style of speech, but rather to highlight the diverse and creative ways in which lesbian and gay Israelis use language to help constitute identities that are at once sexual and political. These identities, emerging as they do from a confluence of multiple and at times conflicting social identifications and affiliations, resist classification in static or binary terms, and instead force us to re-conceptualize the ways in which sexuality may be both experienced and linguistically materialized. (Levon, 2010, p. 1)

Queen makes arguments for a more political understanding of lesbian language. Is it possible that much of contemporary psycholinguistics research has neglected more insular lesbian communities in favour of more liberal/mainstream lesbian communities? If we set gender inversion theory to the side, there is little reason to think that lesbian identity/experience is a mere reversal of gay male identity/experience — nor is there reason to assume that lesbians are a homogenous group.

Other Orientations

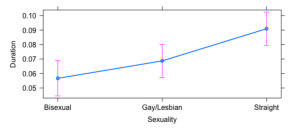

Though literature on lesbian voices is relatively limited compared to literature on the voices of gay men, even fewer studies have looked at bisexuality or other orientation categories. If asked to speak like a stereotypical bisexual person, how many of us would be able to? For many of us, conjuring a stereotype of bisexuality likely doesn’t include a particular way of speaking. In research, bisexual people are usually grouped in with either the gay group or the straight control group, or they’re excluded from studies altogether. However, a few researchers are starting to work with bisexual samples specifically. One such researcher, Chloe Willis, notes that bisexuality is more than a number on the Kinsey scale (2021). Willis (2021) looked at gender conformity and /s/ production among groups of straight, gay, and bisexual men and women. As I briefly touched on earlier, variations in /s/ production are widespread across queer linguistic studies. In terms of duration, a longer /s/ is usually associated with sounding gay. Willis (2021) measured /s/ production on several different aspects and found the most significant result was duration. Not only did her results conflict with the majority of studies that show a longer /s/ correlates with a queer speaker, but bisexual participants had even shorter /s/ duration on average than their gay counterparts (see Figure 2). This goes against the common understanding of bisexuality being an identity based on its place “in between” the worlds of gay and straight. What these results hint at is that bisexuality is likely just as complex an identity as being gay or lesbian, with its own set of linguistic and cultural in-group markers.

Figure 2

Sexuality effect plot from Willis (2021)

Auditory Gaydar

The phenomenon of “gaydar” is increasingly cited in popular culture as the visibility of queer people grows. Gaydar — a portmanteau of “gay” and “radar” — is the ability to identify someone as gay based on implicit cues (Smyth et al., 2002). The idea that a listener might identify someone’s sexual orientation by voice alone goes as far back in literature as the idea of linguistic markers of sexual orientation, if not further. Gaudio’s (1994) study demonstrated that undergraduate students of various sexual orientations were able to correctly guess the sexual orientation of speakers with greater-than-chance accuracy. Likewise, Linville (1998) and Smyth et al. (2002) found similar results, with the addition that listeners were able to guess the sexual orientation of straight speakers more accurately than gay speakers (Linville, 1998; Smyth et al., 2002).

A relatively recent study by Daniele et al. (2020) shows both that listeners can often accurately identify the sexual orientation of speakers, as well as that sounding queer is something that can be purposely exaggerated or toned down in certain contexts — perhaps to combat unwanted gaydar, which could result in discrimination. They did this by first comparing the phonetic features of openly gay men speaking to three different conversation partners: a receiver with whom they had not come out and with whom they would not feel comfortable to come out, a receiver with whom they had come out and who had reacted in a positive way, and a receiver with whom they had come out but who had reacted in a negative way. Between all three conditions, phonetic indications of sexual orientation were highest when the receiver was someone to whom the participants had come out with no negative repercussions. The researchers then edited and spliced the audio and presented clips to a group of listeners (similar to Gaudio’s 1994 procedure). Listeners accurately predicted above chance, performing better when hearing clips from the positive coming out condition, and sexual minority listeners were slightly more accurate in guessing than their straight peers (Daniele et al., 2020).

Conclusions and Further Directions

Although a convenient (and thus attractive) explanation as to the atypical features of many queer voices, gender inversion theory is largely insufficient when considering the wide array of results across studies. Further, there is a lack of evidence supporting the theory in lesbian, bisexual, and asexual populations. Ultimately, gender inversion theory is inseparable from the harmful and discriminatory interpretations of the gay voice, but there are nevertheless many potential differences in the way queer people speak — enough so that listeners have an above-average chance of correctly guessing sexual orientation based on stereotypes. Acknowledgement of the vast array of intricate social factors that influence the gay voice can help remedy the gaps left by the still-popular gender inversion theory. Psycholinguists should continue broadening the scope of queer phonetic research to include more sexual orientation groups such as bisexuals and asexuals (the latter of whom I could find no research at all). It is clear that no one set of phonetic differences set queer populations apart; a focus on how and why such differences are indexed rather than what those differences are will serve to benefit future inquiries and generate insights as to how queer populations communicate within and between in-groups.

References

Daniele, M., Fasoli, F., Antonio, R., Sulpizio, S., & Maass, A. (2020). Gay Voice: Stable Marker of Sexual Orientation or Flexible Communication Device? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(7), 2585–2600. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01771-2

Fasoli, F., Hegarty, P., & Frost, D. M. (2021). Stigmatization of “gay‐sounding” voices: The role of heterosexual, lesbian, and gay individuals’ essentialist beliefs. British Journal of Social Psychology, 60. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12442

Fasoli, F., Maass, A., Paladino, M. P., & Sulpizio, S. (2017). Gay- and Lesbian-Sounding Auditory Cues Elicit Stereotyping and Discrimination. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(5), 1261–1277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-0962-0

Gaudio, R. P. (1994). Sounding Gay: Pitch Properties in the Speech of Gay and Straight Men. American Speech, 69(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.2307/455948

Gratton, C. (2016). Resisting the Gender Binary: The Use of (ING) in the Construction of Non-binary Transgender Identities. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics, 22(2).

Kachel, S., Radtke, A., Skuk, V. G., Zäske, R., Simpson, A. P., & Steffens, M. C. (2018). Investigating the common set of acoustic parameters in sexual orientation groups: A voice averaging approach. PLOS ONE, 13(12), e0208686. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208686

Kachel, S., Simpson, A. P., & Steffens, M. C. (2017). Acoustic correlates of sexual orientation and gender-role self-concept in women’s speech. Citation: The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 141(6).

Kachel, S., Steffens, M. C., Preuß, S., & Simpson, A. P. (2019). Gender (Conformity) Matters: Cross-Dimensional and Cross-Modal Associations in Sexual Orientation Perception. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 39(1), 40–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927×19883902

Kite, M. E., & Deaux, K. (1987). Gender Belief Systems: Homosexuality and the Implicit Inversion Theory. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1987.tb00776.x

Law, A. (2016). Sexual orientation, phonetic variation and the roots and accuracy of perception in the speech of Northern England English-speaking men.

Levon, E. (2009). Dimensions of style: Context, politics and motivation in gay Israeli speech. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 13(1), 29–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2008.00396.x

Levon, E. (2014). Categories, stereotypes, and the linguistic perception of sexuality. Language in Society, 43(5), 539–566. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0047404514000554

Linville, S. E. (1998). Acoustic Correlates of Perceived versus Actual Sexual Orientation in Men’s Speech. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica, 50(1). https://doi.org/10.1159/000021447

Listen Lab. (2020). Speech Acoustics – Expression of Gender. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TWRB443YrHI

Merriam-Webster. (2019). Gender. In Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/gender

Merriam-Webster. (2023). Gender Nonconformity. In Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/gender%20nonconformity

Moonwomon-Baird, B. (1997). Toward a Study of Lesbian Speech. In Queerly Phrased: Language, Gender, and Sexuality. Oxford University Press.

Munson, B., McDonald, E. C., DeBoe, N. L., & White, A. R. (2006). The acoustic and perceptual bases of judgments of women and men’s sexual orientation from read speech. Journal of Phonetics, 34(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wocn.2005.05.003

Queen, R. M. (1997). “I Don’t Speak Spritch”: Locating Lesbian Language. In Queerly Phrased: Language, Gender, and Sexuality. Oxford University Press.

Rendall, D., Vasey, P. L., & McKenzie, J. (2008). The Queen’s English: An Alternative, Biosocial Hypothesis for the Distinctive Features of “Gay Speech.” Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9269-x

Sedivy, J. (2020). Language in Mind: An Introduction to Psycholinguistics. Oxford University Press.

Smyth, R., Jacobs, G., & Rogers, H. (2003). Male voices and perceived sexual orientation: An experimental and theoretical approach. Language in Society, 32(3). https://doi.org/10.1017/s0047404503323024

Sulpizio, S., Fasoli, F., Antonio, R., Eyssel, F., Paladino, M. P., & Diehl, C. (2019). Auditory Gaydar: Perception of Sexual Orientation Based on Female Voice. Language and Speech, 63(1), 184–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0023830919828201

Sulpizio, S., Fasoli, F., Maass, A., Paladino, M. P., Vespignani, F., Eyssel, F., & Bentler, D. (2015). The Sound of Voice: Voice-Based Categorization of Speakers’ Sexual Orientation within and across Languages. PLOS ONE, 10(7), e0128882. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0128882

Tripp, A., & Munson, B. (2021). Perceiving gender while perceiving language: Integrating psycholinguistics and gender theory. WIREs Cognitive Science, 13(2). https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1583

Van Borsel, J., De Bruyn, E., Lefebvre, E., Sokoloff, A., De Ley, S., & Baudonck, N. (2009). The prevalence of lisping in gay men. Journal of Communication Disorders, 42(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2008.08.004

Waksler, R. (2001). Pitch range and women’s sexual orientation. Word, 52(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/00437956.2001.11432508

White, T. (2022). What Does It Mean to Be Gender Nonconforming? Psych Central. https://psychcentral.com/health/gender-nonconforming

Willis, C. (2021). Bisexuality and /s/ production. Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America, 6(1), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.3765/plsa.v6i1.4942

Zimman, L. (2018). Transgender voices: Insights on identity, embodiment, and the gender of the voice. Language and Linguistics Compass, 12(8), e12284. https://doi.org/10.1111/lnc3.122