Main Body

Society and Modern Life

Dr. William Little and Ron McGivern

Learning Objectives

Types of Societies

- Compare ways of understanding the evolution of human societies.

- Describe the difference between preindustrial, industrial, postindustrial and postnatural societies.

- Understand how a society’s relationship to the environment impacts societal development.

Theoretical Perspectives on the Formation of Modern Society

- Describe Durkheim’s functionalist view of modern society.

- Understand the critical sociology view of modern society.

- Explain the difference between Marx’s concept of alienation and Weber’s concept of rationalization.

- Identify how feminists analyze the development of society.

Living in Capitalist Society

- Understand the relationship between capitalism and the incessant change of modern life.

- Figure 1. Effigy of a Shaman from Haida Tribe, late 19th century

- Source: (Image courtesy of Wellcome Library, London/Wikimedia Commons). “Effigy of a Shaman from Haida Tribe, late 19th century” from Wellcome Library (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Haida#/media/File:Effigy_of_a_Shaman_from_Haida_Tribe,_late_19th_century._Wellcome_L0007356.jpg) is licensed under CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Introduction to Society

In 1900 a young anthropologist, John Swanton, transcribed a series of myths and tales — known as qqaygaang in the Haida language — told by the master Haida storyteller Ghandl. The tales tell stories of animal and human transformations, of heroes who marry birds, of birds who take off their skins and become women, of mussels who manifest the spirit form of whales, and of poles climbed to the sky.

After she’d offered him something to eat, Mouse Woman said to him, “When I was bringing a bit of cranberry back from my berry patch, you helped me. I intend to lend you something I wore for stalking prey when I was younger.”

She brought out a box. She pulled out four more boxes within boxes. In the innermost box was the skin of a mouse with small bent claws. She said to him, “Put this on.”

Small though it was, he got into it. It was easy. He went up the wall and onto the roof of the house. And Mouse Woman said to him, “You know what to do when you wear it. Be on your way” (Ghandl, quoted in Bringhurst, 2011).

To the ear of contemporary Canadians, these types of tales often seem confusing. They lack the standard inner psychological characterization of protagonists and antagonists, the “realism” of natural settings and chronological time sequences, or the plot devices of man against man, man against himself, and man against nature. However, as Robert Bringhurst (2011) argues, this is not because the tales are not great literature or have not completely “evolved.” In his estimation, Ghandl should be recognized as one of the most brilliant storytellers who has ever lived in Canada. Rather, it is because the stories speak to, and from, a fundamentally different experience of the world: the experience of nomadic hunting and gathering people as compared to the sedentary people of modern capitalist societies. How does the way we tell stories reflect the organization and social structures of the societies we live in?

Ghandl’s tales are told within an oral tradition rather than a written or literary tradition. They listen to, not read, and the storytelling skill involves weaving in subtle repetitions and numerical patterns, and plays on Haida words and well-known mythological images rather than creating page-turning dramas of psychological or conflictual suspense. Bringhurst suggests that even compared to the Indo-European oral tradition going back to Homer or the Vedas, the Haida tales do not rely on the auditory conventions of verse. Whereas verse relies on acoustic devices like alliteration and rhyming, Haida mythic storytelling was a form of noetic prosody, relying on patterns of ideas and images. The Haida, as a preagricultural people, did not see a reason to add overt musical qualities to their use of language. “[V]erse in the strictly acoustic sense of the word does not play the same role in preagricultural societies. Humans, as a rule, do not begin to farm their language until they have begun to till the earth and to manipulate the growth of plants and animals.” As Bringhurst puts it, “myth is that form of language in which poetry and music have not as yet diverged“(Bringhurst, 2011, italics in original).

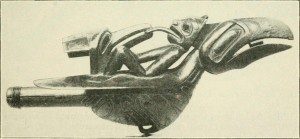

Figure 2. A Haida ceremonial rattle as the mythical thunder bird

Source: (Photo courtesy of British Museum/Wikimedia Commons). “Ceremonial rattle in the form of the mythical thunder-bird” from the British Museum Handbook to the Ethnographical Collections (1910) by Internet Archive Book Images (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Haida#/media/File:Handbook_to_the_ethnographical_collections_%281910%29_%2814596714720%29.jpg) is licensed under the rule that “no known copyright restrictions” exist (https://www.flickr.com/commons/usage/)

Perhaps more significantly for sociologists, the hunting and gathering lifestyle of the Haida also produces a very different relationship to the natural world and to the non-human creatures and plants with which they coexisted. This is manifest in the tales of animal-human-spirit transformations and in their moral lessons, which caution against treating the world with disrespect. Regarding understanding Haida storytelling, Bringhurst argues that following the poetry they [hunting gathering peoples] make is more like moving through a forest or a canyon, or waiting in a blind, than moving through an orchard or field. The language is often highly ordered, rich, compact — but it is not arranged in neat, symmetrical rows (2011).

For the hunter who follows animal traces through the woods, or waits patiently for hours in a hunting blind or fishing spot for wild prey to appear, the relationship to the prey is much more akin to “putting on their skins” or spiritually “becoming-animal” than to be a shepherd raising livestock. It would incline a successful hunting and gathering people to study how animals think from the inside, rather than controlling or manipulating them from the outside. For the Haida, tales of animal transformations would not seem so fantastic or incomprehensible as they do to modern people who spend most of their life indoors. They would be part of their “acutely personal relations with the wild” (Bringhurst, 2011).

Similarly, the Haida ethics, embodied in their tales and myths, acknowledge a complex web of unwritten contracts between humans, animal species, and spirit-beings. The culture as Ghandl describes it depends — like every hunting culture — not on control of the land as such but on control of the human demands that are placed upon it (Bringhurst, 2011).

In the tales, humans continually confront a world of living beings and forces that are much more powerful and intelligent than they are, and who are quick to take offense at human stupidity and hubris.

What sociologists learn from the detailed studies of the Haida and their literature is how a different social relationship to the environment affects the way people think and how they see their place in the world. Although the traditional Haida society of Haida Gwaii in the Pacific Northwest differs from that of contemporary post-industrial Canada, I can see both as different ways of expressing the human need to cooperate and live together in order to survive. For the sociologist, this is a lesson in how the type of society one lives in — its scale and social structure — impacts one’s experience of the world at a very fundamental perceptual level.

Types of Societies

Haida, Maasai, modern Canadians — each is a society. But what does this mean? Exactly what is a society? In sociological terms, a society refers to a group of people who interact in a definable territory and share the same culture. In practical, everyday terms, societies comprise various types of institutional constraint and coordination exercised over our choices and actions. The type of society we live in determines the nature of these types of constraint and coordination. The nature of our social institutions, the type of work we do, the way we think about ourselves and the structures of power and social inequality that order our life chances are all products of the type of society we live in and thus vary globally and historically.

The founder of sociology, August Comte (1798–1857), provided the first sociological theory of the evolution of human societies. His best known sociological theory was the law of three stages, which held that all human societies and all forms of human knowledge develop through three distinct stages from primitive to advanced: the theological, the metaphysical, and the positive. The key variable in defining these stages was the way a person conceptualized causation or how they understood their place in the world.

In the theological stage, humans explain causes in terms of the will of anthropocentric gods (the gods cause things to happen). In the metaphysical stage, humans explain causes in terms of abstract, “speculative” ideas like nature, natural rights, social contracts, or “self-evident” truths. This was the basis of Comte’s critique of the Enlightenment philosophers whose ideas about natural rights and freedoms had led to the French Revolution but also to the chaos of its aftermath. In his view, the “negative” or metaphysical knowledge of the philosophers was based on dogmatic ideas that could not be reconciled when they were in contradiction. This lead to inevitable conflict and moral anarchy. Finally, in the positive stage, humans explain causes in terms of positivist, scientific observations and laws (i.e., “positive” knowledge based on propositions limited to what can be empirically observed). Comte believed that this would be the last stage of human social evolution because positivist science could empirically determine how society should be organized. Science could reconcile the division between political factions of order and progress by eliminating the basis for moral and intellectual anarchy. The application of positive philosophy would lead to the unification of society and of the sciences (Comte, 1830/1975).

Karl Marx offered another model for understanding the evolution of types of society. Marx argued that the evolution of societies from primitive to advanced was not a product of the way people thought, as Comte proposed, but of the power struggles in each epoch between different social classes over control of property. The key variable in his analysis was the different modes of production or “material bases” that characterized different forms of society: from hunting and gathering, to agriculture, to industrial production. This historical materialist approach to understanding society explains both social change and the development of human ideas to underlie changes in the mode of production. The type of society and its level of development is determined principally by how a person produces the material goods needed to meet its needs. Their world view, including the concepts of causality described by Comte, followed by the way of thinking involved in the society’s mode of production.

On this basis, Marx categorized the historical types of society into primitive communism, agrarian/slave societies, feudalism, and capitalism. Primitive communists, for example, are hunter gatherers like the Haida whose social institutions and worldview develop in sync with their hunting and gathering relationship to the environment and its resources. They are defined by their hunter-gatherer mode of production.

Marx went on to argue that the historical transformations from one type of society to the next are generated by the society’s capacity to generate economic surpluses and the conflicts and tensions that develop when one class monopolizes economic power or property: land owners over agricultural workers, slave owners over slaves, feudal lords over serfs, or capitalists over labourers. These class dynamics are inherently unstable and eventually lead to revolutionary transformations from one mode of production to the next.

To simplify Comte’s and Marx’s schemas, we might examine the way different types of society are structured around their relationship to nature. Sociologist Gerhard Lenski (1924-2015) defined societies in terms of their technological sophistication. With each advance in technology the relationship between humans and nature is altered. Societies with rudimentary technology are at the mercy of the fluctuations of their environment, while societies with industrial technology have more control over their environment, and thus develop different cultural and social features. Societies with rudimentary technology make relatively little impact on their environment, while industrial societies transform it radically. The changes in the relationship between humans and their environment in fact goes beyond technology to encompass all aspects of social life, including its mental life (Comte) and material life (Marx). Distinctions based on the changing nature of this relationship enable sociologists to describe societies along a spectrum: from the foraging societies that characterized the first 90,000 years of human existence to the contemporary post natural, anthropocene societies in which human activity has made a substantial impact on the global ecosystem.

Preindustrial Societies

Before the Industrial Revolution and the widespread use of machines, societies were small, rural, and dependent on local resources. Economic production was limited to the amount of labour a human being could provide, and there were few specialized occupations. Production was (mostly) for immediate consumption, although evidence of trade between groups also goes back to the earliest archaeological records. The very first occupation was that of hunter-gatherer.

Hunter-Gatherer Societies

- Figure 4. The Blackfoot or Siksika were traditionally nomadic hunter-gatherers who moved camp frequently during the summer months to follow the buffalo herds

- Source: (Image courtesy of Library and Archives Canada). “Blackfoot Indians” from Library and Archives Canada (http://collectionscanada.gc.ca/pam_archives/index.php?fuseaction=genitem.displayItem&rec_nbr=3193492&lang=eng) is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain)

Of the various types of preindustrial societies, Hunter-gatherer societies show the strongest dependence on the environment. As the basic structure of all human society until about 10,000–12,000 years ago, these groups were based around kinship or tribal affiliations. Hunter-gatherers relied on their surroundings for survival — they hunted wild animals and foraged for uncultivated plants for food. They survived on what nature provided and immediately consumed what they got. They produced no surpluses. When resources became scarce, the group moved to a new area to find sustenance, meaning they were nomadic. The plains Indians of North America, moved frequently to follow their primary source of food. Some groups, like the Haida, lived off of abundant, non-depleting resources like fish, which enabled them to establish permanent villages where they could dwell for long periods of the year before dispersing to summer camps. (See “People of the Far Northwest” below).

Most of the caloric intake of hunters and gatherers came from foraging for edible plants, fruits, nuts, berries, and roots. The largely meat-based diet of the Inuit is a notable exception. Richard Lee (1978) estimated that approximately 65% of the hunter-gatherer diet came from plant sources, which had implications for the gender egalitarianism of these societies. With the earliest economic division of labour being between male hunters and women gatherers, the fact that women accounted for the largest portion of the food consumed by the community ensured the importance of their status within the group. Early reports of missionaries among the Algonquins of the north shore of Lake Superior observed women with their noses cut off and small parts of their scalp removed as punishment for adultery, suggesting that (at least among some groups) female subordination was common. Male Algonquins often had seven or eight wives (Kenton, 1954).

Because of their unique relationship and dependence on the environment for sustenance, the ideal type or model that characterized hunter-gatherer societies includes several common features (Diamond, 1974):

- The distribution of economic surplus is organized on a communalistic, shared basis in which there is little private property, work is cooperative, and gift giving is extensive. The use of resources was governed by the practice of usufruct, the distribution of resources according to need (Bookchin, 1982).

- Power is dispersed either shared equally within the community, or shifting between individual members based on individual skills and talents.

- Social control over the members of society is exercised through shared customs and sentiment rather than through the development of formal law or institutions of law enforcement.

- Society is organized based on kinship and kinship ties so there are few, if any, social functions or activities separate from family life.

- There is little separation between the spheres of intimate private life and public life. Everything is a matter of collective concern.

- The life of the community is all “personal” and emotionally charged. There is little division of labour so there is no social isolation.

- Art, story telling, ethics, religious ritual and spirituality are all fused together in daily life and experience. They provide a common means of expressing imagination, inspiration, anxiety, need and purpose.

One interesting aspect of hunter-gatherer societies that runs counter to modern prejudices about “primitive” society, is how they developed mechanisms to prevent their evolution into more “advanced” sedentary, agricultural types of society. For example, in the “headman” structure, the authority of the headman or “titular chief” rests entirely on the ongoing support and confidence of community members rather than permanent institutional structures. This is a mechanism that actively wards off the formation of permanent institutionalized power (Clastres, 1987). The headman’s main role is as a diplomatic peacemaker and dispute settler, and he held sway only so long as he maintained the confidence of the tribe. Beyond a headman’s personal prestige, fairness in judgement and verbal ability, there was no social apparatus to enable a permanent institutional power or force to emerge.

Similarly, the Northwest Pacific practice of the potlatch, in which goods, food, and other material wealth were regularly given away to neighbouring bands, provided a means of redistributing wealth and preventing permanent inequality in developing. Evidence also shows that even when hunter-gatherers lived in proximity with agriculturalists they were not motivated to adopt the agricultural mode of production because the diet of early agricultural societies was significantly poorer in nutrition (Stavrianos, 1990; Diamond, 1999). Recent evidence from archaeological sites in the British Isles suggests, for example, that early British hunter-gatherers traded for wheat with continental agriculturalists 2,000 years before they adopted agricultural economies in ancient Britain (Smith et. al., 2015; Larson, 2015). They had close contact with agriculturalists but were not inclined to adopt their sedentary societal forms, presumably because there was nothing appealing about them.

These societies were common until several hundred years ago, but today only a few hundred remain in existence, such as indigenous Australian tribes sometimes referred to as “aborigines,” or the Bambuti, a group of pygmy hunter-gatherers living in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Still, in 2014, members of the Amazonian Mashco-Piro clan emerged out of their voluntary isolation at the border of Peru and Brasil to make “first contact” with the Brazilian government’s Indigenous people’s authority (Funai) in order to seek protection from suspected drug-traffickers (Collins, 2014). Hunter-gatherer groups largely disappeared under the impact of colonization and European diseases, but we estimate that another 75 uncontacted tribes still inhabit the Amazonian rainforest.

Making Connections: Big Picture

People of the Far Northwest

- Figure 5. The Salish Sea (as Georgia Strait is now widely known) was an ecologically and culturally rich zone occupied by related but unallied peoples

- Source: (Image courtesy of Arct/Wikimedia Commons). “The Salish Sea” by Arct (https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/ab/Carte_populations_salish_de_la_cote.svg) is licenced under CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The Pacific Northwest region was utterly separate from the Plains and other cultural zones. Its peoples were many and they shared several cultural features that were unique to the region.

By the 1400s there were at least five distinct language groups on the West Coast, including Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Wakashan, and Salishan, all of which divide into many more dialects. However, these differences (and there are many others) are overshadowed by cultural similarities across the region. An abundance of food from the sea meant that coastal populations enjoyed comparatively high fertility rates and life expectancy. Population densities were, as a consequence, among the highest in the Americas.

The people of the Pacific Northwest do not share the agricultural traditions that existed east of the Rockies, nor did they influence Plains and other cultures. There was, however, a long and important relationship of trade and culture between the coastal and interior peoples. In some respects it is appropriate to consider the mainland cultures as inlet-and-river societies. The Salish-speaking peoples of the Straight of Georgia (Salish Sea) share many features with the Interior Salish (Okanagan, Secwepemc, Nlaka’pamux, Stl’atl’imx), though they are not as closely bound as the peoples of the Skeena and Stikine Valleys (which include the Tsimshian, the Gitxsan, and the Nisga’a). Running north of the Interior Salish nations through the Cariboo Plateau, and flanked on the west by the Coast Mountain Range, are societies associated with the Athabascan language group. Some of these peoples took on cultural habits and practices more typically associated with the Pacific Northwest coastal traditions than with the northern Athabascan peoples who cover a swath of territory from Alaska to northern Manitoba. In what is now British Columbia, the Tsilhqot’in, the Dakelh, Wet’suwet’en, and Sekani were part of an expansive, southward-bound population that sent offshoots into the Nicola Valley and deep into the southwest of what is now the United States.

Most coastal and interior groups lived in large, permanent towns in the winter, and these villages reflected local political structures. Society in Pacific Northwest groups was generally highly stratified and included, most times, an elite, a commoner class, and a slave class. The Kwakwaka’wakw, whose domain extended in pre-contact times from the northern tip of Vancouver Island south along its east coast to Quadra Island and possibly farther, assembled kin groups (numayms) as part of a system of social rank in which all groups were ranked in relation to others. Each kin group “owned” names or positions that were also ranked. An individual could hold over one name; some names were inherited, and they gained others through marriage. In this way, an individual could gain rank through kin associations, although kin groups themselves had ascribed ranks. Movement in and out of slavery was even possible.

The fact that slavery existed points to the competition that existed between coastal rivals. The Haida, Tsimshian, Haisla, Nuxalk, Heiltsuk, Wuikinuxv (Oowekeeno), Kwakwaka’wakw, Pentlatch/K’ómoks, and Nuu-chah-nulth regularly raided one another and their Stó:lō neighbours. Many of the winter towns were or other fortified and small stone defensive sniper blinds can still be discerned in the Fraser Canyon. The large number of oral traditions that arise from this era regularly reference conflict and the severe loss of personnel. Natural disasters are also part of the oral tradition: they tell of massive and apocalyptic floods and volcanic explosions and other seismic (and tidal) events that had tremendous impacts on local populations.

The practice of potlatch (a public feast held to mark important community events, deaths, ascensions, etc.) is a further commonality. It involved giving away property and thus redistributing wealth as a means for the host to maintain, reinforce, and even advance through the complex hierarchical structure. In receiving property at a potlatch an attendee was committing to act as a witness to the legitimacy of the event being celebrated. The size of potlatching varied radically and would develop along new lines in the post-contact period, but the outlines and protocols of this cultural trademark were well-elaborated centuries before the contact moment. Potlatching was universal among the coastal peoples and could also be found among more inland upriver societies as well.

Horticulture — the domestication of some plants — was another important source of food. West Coast peoples and the nations of the Columbia Plateau (which covers much of southern inland British Columbia), like many eastern groups, applied controlled burning to eliminate underbrush and open up landscape to berry patches and meadows of camas plants that were gathered for their potato-like roots. This required somewhat less labour than farming (although harvesting root plants is never light work), and it functioned within a strategy of seasonal camps. Communities moved from one food crop location to another for preparation and then harvest. Much of the land seized upon by early European settlers in the Pacific Northwest included these berry patches and meadows. These were attractive sites because they had been cleared of enormous trees and comprised mostly open and well-drained pasture. Europeans would see these spaces as pastoral, natural, and available rather than anthropogenic (human-made) landscapes — the product of centuries of horticultural experimentation.

“People of the Far Northwest” excerpted from John Belshaw, 2015, Canadian History: Pre-Confederation, (Vancouver: BCCampus). Used under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Horticultural and Pastoral Societies

- Figure 6. Teocinte (top) is the undomesticated ancestor of modern corn (bottom)

- Teocintes were the natural source of one of the most important food crops cultivated by the horticultural societies of Mesoamerica. Source: (Image courtesy of John Doebley/Wikimedia Commons). “Maize-teosinte” by John Doebley (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Maize-teosinte.jpg) is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported licence.

Around 10,200 BCE, another type of society developed in ancient Anatolia, (now part of Turkey), based on the newly developed capacity for people to grow and cultivate plants. Previously, the depletion of a region’s crops or water supply forced hunter-gatherer societies to move in search of food sources. Horticultural societies formed in areas where rainfall and other conditions provided fertile soils to grow stable crops with simple hand tools. Their increasing control over nature decreased their dependence on shifting environmental conditions for survival. They no longer had to abandon their location to follow resources and could find permanent settlements. The new horticultural technology created more stability and dependability, produced more material goods and provided the basis for the first revolution in human survival: the Neolithic revolution.

Changing conditions and adaptations also led some societies to rely on the domestication of animals where circumstances permitted. Roughly 8,000 BCE, human societies recognized their ability to tame and breed animals. Pastoral societies rely on the domestication of animals as a resource for survival. Unlike earlier hunter-gatherers who depended entirely on existing resources to stay alive, pastoral groups could breed livestock for food, clothing, and transportation, creating a surplus of goods. Herding, or pastoral, societies remained nomadic because they were forced to follow their animals to fresh feeding grounds.

With the emergence of horticultural and pastoral societies during the Neolithic revolution, stable agricultural surpluses were generated, population densities increased, specialized occupations developed, and societies began sustained trading with other local groups. Feuding and warfare also grew with the accumulation of wealth. One of the key inventions of the Neolithic revolution therefore was structured social inequality: the development of a class structure based on the appropriation of surpluses. A social class can be defined as a group that has a distinct relationship to the means of production. In Neolithic societies, based on horticulture or animal husbandry as their means of production, control of land or livestock became the first form of private property that enabled one relatively small group to take the surpluses while another much larger group produced them. For the first time in history, societies were divided between producing classes and owning classes. As control of land was the source of power in Neolithic societies, ways of organizing and defending it became a more central preoccupation. The development of permanent administrative and military structures, taxation, as well as the formation of specialized priestly classes to spiritually unite society originated based on the horticultural and pastoral relationship to nature.

Agricultural Societies

- Figure 7. Roman collared slaves depicted in a marble relief from Smyrna (modern Turkey) in 200 CE

- Source: (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons). “Roman Collared Slaves” from the Collection of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, England (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Slavery_in_ancient_Rome#/media/File:Roman_collared_slaves_-_Ashmolean_Museum.jpg) is licenced under CC BY-SA 2.0.

While pastoral and horticultural societies used small, temporary tools such as digging sticks or hoes, agricultural societies relied on permanent tools for survival. Around 3,000 BCE, an explosion of new technology known as the Agricultural Revolution made farming possible — and profitable. Farmers learned to rotate the types of crops grown on their fields and to reuse waste products such as fertilizer, which led to better harvests and bigger surpluses of food. New tools for digging and harvesting were made of metal, making them more effective and longer lasting. Human settlements grew into towns and cities, and particularly bountiful regions became centres of trade and commerce.

This era in which some classes of people had the time and comfort to engage in more contemplative activities, such as music, poetry, and philosophy, became referred to as the “dawn of civilization” by some because of the development of leisure and arts. Craftspeople could support themselves through the production of creative, decorative, or thought-provoking aesthetic objects and writings.

As agricultural techniques made the production of surpluses possible, social classes and power structures became further entrenched. Kinship ties became secondary to other forms of social allegiance and power. Those with the power to appropriate the surpluses could dominate the society on a wider scale than ever before. Classes of nobility and religious elites developed. As cities expanded, ownership and protection of resources became an ever pressing concern and the militarization of society became more prominent. Difference in social standing between men and women, already started in Neolithic societies, became more pronounced and institutionalized. Slavery — the ownership and control of humans as property — was also institutionalized as a large scale source of labour. In the agricultural empires of Greece and Rome, slavery was the dominant form of class exploitation. However, as they largely gained slaves through military acquisition, ancient slavery as an institution was inherently unstable and inefficient.

Feudal Societies

In Europe, the 9th century gave rise to feudal societies. Feudal societies were still agriculturally based but organized according to a strict hierarchical system of power founded on land ownership, military protection, and duties or mutual obligations between the different classes. Feudalism is usually used in a restricted sense by historians to describe the societies of post-Roman Europe, from roughly the 9th to the 15th centuries (the “middle ages”), although these societies bare striking resemblance to the hierarchical, agricultural-based societies of Japan, China, and pre-contact America (e.g., Aztec, Inca) of the same period.

- Figure 8. Tapestry from the 1070s in which King Harold swears an oath to become the vassal of Duke William of Normandy

- Source: (Photo courtesy of Myrabella/Wikimedia Commons). Bayeux Tapestry – Scene 23 by Myrabella (http://uk.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%A4%D0%B0%D0%B9%D0%BB:Bayeux_Tapestry_scene23_Harold_oath_William.jpg) is in the public domain (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/deed.en).

In Europe the class system of feudalism was organized around the parceling out of manors or estates by the aristocracy to vassals and knights in return for their military service. The nobility, known as lords, rewarded knights or vassals by granting them pieces of land. In return for the resources that the land provided, vassals promised to fight for their lords. These individual pieces of land, known as fiefdoms, were cultivated by the lower class of serfs. Serfs were not slaves, in that they were at least nominally free men and women, but they produced agricultural surpluses for lords primarily through forced agricultural service. In return for maintaining and working the land, serfs were guaranteed a place to live and military protection from outside enemies. They could produce food and goods for their own consumption on private land allotments, or on common allotments shared by the community. Power in feudal society was handed down through family lines, with serf families serving lords for generations and generations.

In later forms of feudalism, the forced labour of the serfs was gradually replaced by a system of rents and taxation. Serfs worked their own plots of land but gave their lords a portion of what they produced. Gradually payment as goods and agricultural surplus was replaced by payment as money. This prompted the development of markets in which the exchange of goods through bartering was replaced by the exchange of goods for money. This was the origin of the money economy. In bartering, the buyer and the seller have to need each other’s goods. In a market economy, goods are exchanged into a common medium of value — money — which can then be exchanged for goods of any nature. Markets therefore enabled goods and services to be bought and sold on a much larger scale and in a much more systematic and efficient way. Money also enabled land to be bought and sold instead of handed down through hereditary right. Money could be accumulated and financial debts could be incurred.

Ultimately, the social and economic system of feudalism was surpassed by the rise of capitalism and the technological advances of the industrial era, because money allowed economic transactions to be conceived and conducted in an entirely new way. In particular, the demise of feudalism was started by the increasing need to intensify labour and improve productivity as markets became more competitive and the economy less dependent on agriculture.

Industrial Societies

- Figure 9. Wrapping bars of soap at the Colgate-Palmolive Canada plant, Toronto, 1919

- Source: (Image courtesy of the Toronto Public Library/Wikimedia Commons). “Women wrapping and packing bars of soap in the Colgate-Palmolive Canada plant on the northwest corner of Carlaw and Colgate Avenues in Toronto, Ontario, Canada” by Pringle & Booth, Toronto (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Colgate-Palmolive_Canada_1919.jpg) is in the public domain (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

In the 18th century, Europe experienced a dramatic rise in technological invention, ushering in an era known as the Industrial Revolution. What made this period remarkable was the number of new inventions that influenced people’s daily lives. Within a generation, tasks that had until this point required months of labour became achievable in a matter of days. Before the Industrial Revolution, work was largely person- or animal-based, relying on human workers or horses to power mills and drive pumps. In 1782, James Watt and Matthew Boulton created a steam engine that could do the work of 12 horses by itself.

Steam power began appearing everywhere. Instead of paying artisans to painstakingly spin wool and weave it into cloth, people turned to textile mills that produced fabric quickly at a better price, and often with better quality. Rather than planting and harvesting fields by hand, farmers could purchase mechanical seeders and threshing machines that caused agricultural productivity to soar. Products such as paper and glass became available to the average person, and the quality and accessibility of education and health care soared. Gas lights allowed increased visibility in the dark, and towns and cities developed a nightlife.

One result of increased wealth, productivity, and technology was the rise of urban centres. Serfs and peasants, expelled from their ancestral lands, flocked to the cities in search of factory jobs, and the populations of cities became increasingly diverse. The new generation became less preoccupied with maintaining family land and traditions, and more focused on survival. Some were successful in acquiring wealth and achieving upward mobility for themselves and their family. Others lived in devastating poverty and squalor. Whereas the class system of feudalism had been rigid, and resources for all but the highest nobility and clergy were scarce, under capitalism social mobility (both upward and downward) became possible.

It was during the 18th and 19th centuries of the Industrial Revolution that sociology was born. Life was changing quickly and the long-established traditions of the agricultural eras did not apply to life in the larger cities. Masses of people were moving to new environments and often found themselves faced with horrendous conditions of filth, overcrowding, and poverty. Social science emerged in response to the unprecedented scale of the social problems of modern society.

It was during this time that power moved from the hands of the aristocracy and “old money” to the new class of rising bourgeoisie who could amass fortunes in their lifetimes. In Canada, a new cadre of financiers and industrialists like Donald Smith (1st Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal) and George Stephen (1st Baron Mount Stephen) became the new power players, using their influence in business to control aspects of government as well. Eventually, concerns over the exploitation of workers led to the formation of labour unions and laws that set mandatory conditions for employees. Although introducing new “postindustrial” technologies (like computers) at the end of the 20th century ended the industrial age, much of our social structure and social ideas — such as the nuclear family, left-right political divisions, and time standardization — have a basis in industrial society.

- Figure 10. George Stephen

- George Stephen, one of the Montreal consortium who financed and built the Canadian Pacific Railway, grew up the son of a carpenter in Scotland. He was titled 1st Baron Mount Stephen in 1891. The Canadian Pacific Railway was a risky financial venture but as Canada’s first transcontinental railroad, it played a fundamental role in the settlement and development of the West. Source: (Photo courtesy of McCord Museum, File no. I-14179.1 Wikimedia Commons). George Stephen, 1965 by William Notman (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:George_Stephen_1865.jpg) is in the public domain (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Postindustrial Societies

- Figure 11. The ubiquitous e-work place of the 21st century

- Source: (image courtesy of Charlie Styr/Flickr). “The Desk” by Charlie Styr (https://www.flickr.com/photos/charlies/2169080948/in/photolist-4iF7co-fmDBN8-3pzKHj-e2csN-85Dpd2-4BqJnq-75xCjy-q7KdMT-51QJr6-5sju9H-fCxYb-6hGrSD-42cG24-48EdkK-4efHw-uXGV-fMf6tz-4m2KcX-4qMa6h-69EPSh-a1wJSS-72Tcj-6monK8-65bexe-2DEEG-ESpP9-6K4ZT-bx3waG-4UcxqQ-7qa26u-juiu4o-K43C-9w84j8-7cEtjU-a1cYj4-a8LLoY-Cvhkq-5xWXdu-7bWBVz-9DhQX-3sjha-9kYneT-u8WdY-2cnSAW-8dNu6-b1UmA-4TannF-4xYr78-6549S-238pk) used under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/).

Information societies, sometimes known as postindustrial or digital societies, are a recent development. Unlike industrial societies that are rooted in the production of material goods, it based information societies on the production of information and services.

Digital technology is the steam engine of information societies, and high-tech companies such as Apple, Microsoft and RIM are its version of railroad and steel manufacturing corporations. Since knowledge and not material goods drives the economy of information societies, power lies with those in charge of creating, storing, and distributing information. Members of a postindustrial society are likely to be employed as sellers of services — software programmers or business consultants, for example — instead of producers of goods. Access to education divides social classes, since without technical and communication skills, people in an information society lack the means for success.

Postnatural Society: The Anthropocene

- Figure 12. Advances in micro-biochemistry make it possible to manipulate the body at the molecular level

- Source: (image courtesy of Sanofi Pasteur/Flickr). “Dengue virus infection” by Sanofi Pasteur (https://www.flickr.com/photos/sanofi-pasteur/7413644166/in/photolist-ci7S89-5Vy3Ut-5Vyx2q-pCYRsM-4vxwP5-ci7S77-9gtqfe-93BsfE-b5g5E-93Bmkb-93Bu23-93yoH8-8r1Hp8-hiRYTp-8ctWbd-qoxb4p-93T2b2-ci7S4h-b6du8n-dPiDp3-9wkUwH-9WSppU-qbhZUY-r3TuCM-aronSf-93ym6K-ci7S5W-bm1us-8rnwZu-dSPMSp-o42Hvu-93BmPh-kxRVpH-rki4V2-6royED-yP2m87-r3qUcs-yQ1Wyk-tbEDj-xFECFi-9gP97o-9ApBzB-xbr3uW-jQvxq9-rEjNRU-2j1bum-8GSyC4-iK5pRZ-ae7RjF-atrmSD) used under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/).

Recent scientific and technological developments transform the relationship to nature to a such a degree that it is possible to talk about a new postnatural society. Advances in computing, genetics, nano-technology and quantum mechanics create the conditions for society in which the limits imposed by nature are overcome by technological interventions at the molecular level of life and matter. Donna Haraway (1991) describes the new “cyborg” reality that becomes possible when the capacities of the body and mind are enhanced by various prosthetic devices like artificial organs or body parts. When these artificial prosthetics do not simply replace defective anatomy but improve upon it, perhaps the conditions of life have become postnatural. In his science fiction novel Holy Fire (1996), Bruce Sterling extrapolates from recent developments in medical knowledge to imagine a future epoch of posthumanity, i.e., a period in which the mortality that defined the human condition for millennia has effectively been eliminated through the technologies of life preservation.

Through genetic engineering, scientists have been able to create new life forms since the early 1970s. This research is fueled by the prospect of using genetic technologies to solve problems, like disease and aging, at the level of the DNA molecule that contains the “blueprint” of life. Food crops can be designed that are pest-resistant, drought-resistant or more productive. These technologies are therefore theoretically capable of solving environmentally imposed restrictions on our collective ability to feed the hungry. Similarly, nanotechnologies, which allow the physical properties of materials to be engineered at the atomic and subatomic level, pose the possibility of an infinitely manipulable universe. The futurologist Ray Kurzweil (2009) suggests that based on nanotechnology “we’ll be able to create just about anything we need in the physical world from information files with very inexpensive input materials.” Others caution that the complexity of risks posed by introducing these molecular technologies into the environment makes their use decidedly dangerous and their consequences incalculable. This is a very postnatural dilemma; one that would not have occurred to people in earlier types of society.

What are the effects of postnatural technologies on the structure and forms of social life and society? At present, these technologies are extremely capital intensive to develop, which suggests that they will have implications for social inequality — both within societies and globally. Wealthy nations and wealthy individuals will be the most likely beneficiaries. The development of postnatural technologies does not impact the basic structures of capitalism, for the foreseeable future decisions on which avenues of research are to be pursued will be decided solely because of profitable returns. Many competing questions concerning the global risks of the technologies and the ethics of their implementation are secondary to the profit motives of the corporations that own the knowledge.

In terms of the emergent life technologies like genetic engineering or micro-biochemical research, Nikolas Rose (2007) suggests that we are already experiencing five distinct lines of social transformation:

- The “molecularization” of our perspective on the human body, or life in general, implies that we now visualize the body and intervene in its processes at the molecular level. We are “no longer constrained by the normativity of a given order.” From growing skin in a petri dish to the repurposing of viruses, the body can be reconstructed in new, as yet unknown forms because of the pliability of life at the molecular level.

- The technologies shift our attention to the optimization of the body’s capacities rather than simply curing illness. It becomes possible to address our risk and susceptibility to future illnesses or aging processes, just as it becomes feasible to enhance the body’s existing capacities (e.g., strength, cognitive ability, beauty, etc.).

- The relationship between bodies and political life changes to create new forms of biological citizenship. We increasingly construct our identities according to the specific genetic markers that define us, (e.g., “we are the people with Leber’s Amaurosis”), and on this basis advocate for policy changes, accommodations, resources, and research funding, etc.

- The complexity of the knowledge in this field increasingly forces us to submit ourselves to the authority of the new somatic specialists and authorities, from neurologists to genetics counselors.

- As the flows of capital investment in biotechnology and biomedicine shift towards the creation of a new “bioeconomy,” the fundamental processes of life are turned into potential sources of profit and “biovalue.”

Some have described the postnatural period that we are currently living in as the Anthropocene. The anthropocene is defined as the geological epoch following the Pleistocene and Holocene in which human activities have significantly impacted the global ecosystem (Crutzen and Stoermer, 2000). Climate change is the primary example of anthropocenic effect, but it includes several other well-known examples from soil erosion and species extinction to the acidification of the oceans. Of course this impact began at least as early as the 19th century with the effects on the environment caused by the industrial revolution. Arguably, however, it is the recently established knowledge and scientific evidence of these effects which makes up the current era as the anthropocene. In the anthropocene we realize the global nature of the catastrophic risks that human activities pose to the environment. It is also this knowledge that enables the possibility of institutional, economic, and political change to address these issues. Current developments like the use of cap and trade or carbon pricing to factor in the cost the environmental impact into economic calculations, the shift to “green” technologies like solar and wind power, or even curbside recycling have both global implications and direct repercussions for the organization of daily life.

Her-story: The History of Gender Inequality

Missing in the classical theoretical accounts of modernity explains how the developments of modern society, industrialization, and capitalism have affected women differently from men. Despite the differences in Durkheim’s, Marx’s, and Weber’s main themes of analysis, they are equally androcentric to the degree that they cannot account for why women’s experience of modern society is structured differently from men’s, or why the implications of modernity are different for women than they are for men. They tell his-story but neglect her-story.

For most of human history, men and women held more or less equal status in society. In hunter-gatherer societies gender inequality was minimal as these societies did not sustain institutionalized power differences. They were based on cooperation, sharing, and mutual support. There was often a gendered division of labour in that men are most frequently the hunters and women the gatherers and child care providers (although this division is not necessarily strict), but as women’s gathering accounted for up to 80% of the food, their economic power in the society was assured. Where headmen lead tribal life, their leadership is informal, based on influence rather than institutional power (Endicott, 1999). In prehistoric Europe from 7000 to 3500 BCE, archaeological evidence shows that religious life was in fact focused on female deities and fertility, while family kinship was traced through matrilineal (female) descent (Lerner, 1986).

- Figure 13. The Venus of Willendorf

- The Venus of Willendorf discovered in Willendorf, Austria, is thought to be 25,000 years old. It is widely assumed to be a fertility goddess and indicative of the central role of women in Paleolithic society. Source: (Photo courtesy of Matthias Kabel, Wikimedia Commons). Venus of Willendorf by MatthiasKabel (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Venus_of_Willendorf_frontview_retouched_2.jpg) used under CC BY SA 3.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en)

It was not until about 6,000 years ago that gender inequality emerged. With the transition to early agrarian and pastoral types of societies, food surpluses created the conditions for class divisions and power structures to develop. Property and resources passed from collective ownership to family ownership with a corresponding shift in the development of the monogamous, patriarchal (rule by the father) family structure. Women and children also became the property of the patriarch of the family. The invasions of old Europe by the Semites to the south, and the Kurgans to the northeast, led to imposing male-dominated hierarchical social structures and the worship of male warrior gods. As agricultural societies developed, so did the practice of slavery. Lerner (1986) argues that the first slaves were women and children.

The development of modern, industrial society has been a two-edged sword in terms of the status of women in society. Marx’s collaborator Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) argued in The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State (1884/1972) that the historical development of the male-dominated monogamous family originated with the development of private property. The family became the means through which property was inherited through the male line. This also led to the separation of a private domestic sphere and a public social sphere. “Household management lost its public character. It no longer concerned society. It became a private service; the wife became the head servant, excluded from all participation in social production” (1884/1972). Under the system of capitalist wage labour, women were doubly exploited. When they worked outside the home as wage labourers they were exploited in the workplace, often as cheaper labour than men. When they worked within the home, they were exploited as the unpaid source of labour needed to reproduce the capitalist workforce. The role of the proletarian homemaker was tantamount to “open or concealed domestic slavery” as she had no independent source of income herself (Engels, 1884/1972). Early Canadian law, for example, was because the wife’s labour belonged to the husband. This was the case even up to the famous divorce case of Irene Murdoch in 1973, who had worked the family farm in the Turner Valley, Alberta, side by side with her husband for 25 years. When she claimed 50% of the farm assets in the divorce, the judge ruled the farm belonged to her husband, and she was awarded only $200 a month for a lifetime of work (CBC, 2001).

Feminists note that gender inequality was more pronounced and permanent in the feudal and agrarian societies that proceeded capitalism. Women were more or less owned as property, and were kept ignorant and isolated within the domestic sphere. These conditions still exist in the world today. The World Economic Forum Global Gender Gap Report (2014) shows that in a significant number of countries, women are severely restricted regarding economic participation, educational attainment, political empowerment, and basic health outcomes. Yemen, Pakistan, Chad, Syria, and Mali were the five worst countries in the world in terms of women’s inequality.

Yemen is the world’s worst country for women in 2014, according to the WEF. Besides being one of the worst countries in women’s economic participation and opportunity, Yemen received some of the world’s worst scores in relative educational attainment and political participation for females. Just half of women in the country could read, versus 83% of men. Further, women accounted for just 9% of ministerial positions and for none of the positions in parliament. Child marriage is a tremendous problem in Yemen. According to Human Rights Watch, as of 2006, 52% of Yemeni girls were married before they reached 18, and 14% were married before they reached 15 years of age (Hess, 2014).

With the rise of capitalism, Engels noted that there was also an improvement in women’s condition when they worked outside the home. Writers like Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797) in her Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792/1997) could also see, in the discourses of rights and freedoms of the bourgeois revolutions and the Enlightenment, a general “promise” of universal emancipation that could be extended to include the rights of women. The focus of the Vindication of the Rights of Women was on the right of women to have an education, which would put them on the same footing as men regarding the knowledge and rationality required for “enlightened” political participation and skilled work outside the home. Whereas property rights, the role of wage labour, and the law of modern society continued to be a source of gender inequality, the principles of universal rights became a powerful resource for women to use in order to press their claims for equality.

As the World Economic Forum (2014) study reports, “good progress has been made over the last years on gender equality, and sometimes, in a relatively short time.” Between 2006 and 2014, the gender gap in the measures of economic participation, education, political power, and health narrowed for 95% of the 111 countries surveyed. In the top five countries in the world for women’s equality — Iceland, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark — the global gender gap index had closed to 80% or better. (Canada was 19th with a global gender gap index of 75%).

Living in Capitalist Society

One of the key arguments that sociologists draw from Marx’s analysis is to show that capitalism is not simply an economic system, but a social system. The dynamics of capitalism are not a set of obscure economic concerns to be relegated to the business section of the newspaper, but the architecture that underlies the newspaper’s front-page headlines; in fact, every headline in the paper. When Marx was developing his analysis, capitalism was still a relatively new economic system, an economic system characterized by private or corporate ownership of goods and the means to produce them. It was also a system that was inherently unstable and prone to crisis, yet increasingly global within its reach. Today, capitalism has left no place on earth and no aspect of daily life untouched.

As a social system, one of the chief characteristics of capitalism is incessant change, which is why the culture of capitalism is often referred to as modernity. The cultural life of capitalist society can be described as a series of successive “presents,” each of which defines what is modern, new, or fashionable for a brief time before fading away into obscurity like the 78 rpm record, the 8-track tape, and the CD. As Marx and Engels put it, “Constant revolutionizing of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty, and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fast-frozen relations… are swept away, all new ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air…” (1848/1977, p. 224). From the ghost towns that dot the Canadian landscape to the expectation of having a lifetime career, every element of social life under capitalism has a limited duration.

Key Terms

alienation: The condition in which an individual is isolated from his or her society, work, sense of self and/or common humanity.

anomie: A situation of uncertain norms and regulations in which society no longer has the support of a firm collective consciousness.

anthropocene: The geological epoch defined by the impact of human activities on the global ecosystem.

bourgeoisie: The owners of the means of production in a society.

class consciousness: Awareness of one’s class position and interests.

collective conscience: The communal beliefs, morals, and attitudes of a society.

dialectic of culture: How the creation of culture is both constrained by limits given by the environment and a means to go beyond these natural limits.

disenchantment of the world: The replacement of magical thinking by technological rationality and calculation.

ethos: A way of life or a way of conducting oneself in life.

false consciousness: When a person’s beliefs and ideology conflict with his or her best interests.

feudal societies: Agricultural societies that operate on a strict hierarchical system of power based around land ownership, protection and mutual obligations.

horticultural societies: Societies based around the cultivation of plants.

hunter-gatherer societies: Societies that depend on hunting wild animals and gathering uncultivated plants for survival.

industrial societies: Societies characterized by a reliance on mechanized labour to create material goods.

information societies: Societies based on the production of nonmaterial goods and services.

iron cage: A situation in which an individual is trapped by the rational and efficient processes of social institutions.

law of three stages: The three stages of evolution that societies develop through: theological, metaphysical, and positive.

mechanical solidarity: Social solidarity or cohesion through a shared collective consciousness with harsh punishment for deviation from the norms.

metaphysical stage: A stage of social evolution in which people explain events in terms of abstract or speculative ideas.

Neolithic revolution: The economic transition to sedentary, agriculture based societies beginning approximately 10,200 years.

organic solidarity: Social solidarity or cohesion through a complex division of labour, mutual interdependence and restitutive law.

pastoral societies: Societies based around the domestication of animals.

proletariat: The wage labourers in capitalist society.

Protestant work ethic: The duty to work hard in one’s calling.

rationalization: The general tendency in modern society for all institutions and most areas of life to be transformed by the application of rationality and efficiency.

social class: A group defined by a distinct relationship to the means of production.

social integration: How strongly a person is connected to his or her social group.

social structure: General patterns of social behaviour and organization that persist through time.

theological stage: A stage of social evolution in which people explain events regarding the will of God or gods.

Summary

Types of Societies

Societies are classified according to their development and use of technology. For most of human history, people lived in preindustrial societies characterized by limited technology and low production of goods. After the Industrial Revolution, many societies based their economies around mechanized labour, leading to greater profits and a trend toward greater social mobility. At the turn of the new millennium, a new type of society emerged. This postindustrial, or information, society is built on digital technology and nonmaterial goods.

Theoretical Perspectives on the Formation of Modern Society

Émile Durkheim believed that as societies advance, they transition from mechanical to organic solidarity. For Karl Marx, society exists in terms of class conflict. With the rise of capitalism, workers become alienated from themselves and others in society. Sociologist Max Weber noted that the rationalization of society can be taken to unhealthy extremes. Feminists note that the androcentric point of view of the classical theorists does not provide an adequate account of the difference in the way the genders experience modern society.

Exercises

Types of Societies

- How can the difference in the way societies relate to the environment be used to describe the different types of societies that have existed in world history?

- Is Gerhard Lenski right in classifying societies based on technological advances? What other criteria might be appropriate, based on what you have read?

Theoretical Perspectives on Society

- How might Durkheim, Marx, and Weber be used to explain a current social event such as the Occupy movement. Do their theories hold up under modern scrutiny? Are their theories necessarily androcentric?

- Think of the ways workers are alienated from the product and process of their jobs. How can these concepts be applied to students and their educations?

Further Research

Types of Societies

The Maasai are a modern pastoral society with an economy largely structured around herds of cattle. Read more about the Maasai people and see pictures of their daily lives: http://openstaxcollege.org/l/The-Maasai

Theoretical Perspectives on Society

One of the most influential pieces of writing in modern history was Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’ The Communist Manifesto. Visit this site to read the original document that spurred revolutions around the world: http://openstaxcollege.org/l/Communist-Party

References

Bookchin, Murray. (1982). The ecology of freedom: The emergence and dissolution of hierarchy. (Palo Alto, CA.: Cheshire Books).

Carrington, Damian. (2014, August 1). Amazon tribe makes first contact with outside world. The Guardian. Retrieved September 24, 2015 from http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/aug/01/amazon-tribe-makes-first-contact-with-outside-world.

Clastres, Pierre. (1987). Society against the state: Essays in political anthropology. NY: Zone Books

Comte, August. (1975). The nature and importance of the positive philosophy. In Gertrud Lenzer (Ed.), Auguste Comte and positivism: the essential writings. NY: Harper and Row. (original work published 1830)

Crutzen, Paul and Eugene Stoermer, (2000, May). The Anthropocene. [PDF] Global change newsletter. No. 41: 17-18. Retrieved Oct. 4, 2015 from http://www.igbp.net/download/18.316f18321323470177580001401/NL41.pdf.

Diamond, Jared. (1999, May 1). The worst mistake in the history of the human race. Discover. Retrieved Oct. 1, 2015 from http://discovermagazine.com/1987/may/02-the-worst-mistake-in-the-history-of-the-human-race. (originally published in the May 1987 Issue)

Diamond, Stanley. (1974). In search of the primitive. Chicago: Transaction Books

Haraway, Donna. (1991). A cyborg manifesto: Science, technology and socialist-feminism in the late 20th century. Simians, cyborgs and women: The reinvention of nature (Ch. 8). London: Free Association

Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. (2005, July 29). Israel: Treatment of Bedouin, including incidents of harassment, discrimination or attacks; State protection (January 2003–July 2005). Refworld. Retrieved February 10, 2012 (http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/440ed71325.html).

Kenton, Edna. (1954). The Jesuit relations and allied documents. NY: Vanguard Press.

Kjeilen, Tore. (n.d.). Bedouin. Looklex.com. Retrieved February 17, 2012 (http://looklex.com/index.htm).

Kurzweil, Ray. (2009). Ray Kurzweil on the future of nanotechnology. Big think. Retrieved, Oct. 4, 2015, from http://bigthink.com/videos/ray-kurzweil-on-the-future-of-nanotechnology

Larson, Gregor. (2015). How wheat came to Britain. Science, Vol. 347 (6225): 945-946.

Lee, Richard. (1978). Politics, sexual and nonsexual, in an egalitarian society. Social science information, 17.

Maasai Association. (n.d.). Facing the lion: By Massai warriors. Retrieved January 4, 2012 (http://www.maasai-association.org/lion.html).

Marx, Karl. (1977). Preface to a critique of political economy. In D. McLellan (Ed.), Karl Marx: Selected Writings (pp. 388–392). London, UK: Oxford University Press. (original work published 1859)

Rose, N. (2007). The politics of life itself: Biomedicine, power, and subjectivity in the twenty-first century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Smith, Oliver, Garry Momber, Richard Bates, Paul Garwood, Simon Fitch, Mark Pallen, Vincent Gaffney, Robin G. Allaby. (2015). Sedimentary DNA from a submerged site reveals wheat in the British Isles 8000 years ago. Science, Vol. 347 (6225): 998-1001

Stavrianos, Leften. (1990). Lifelines from our past: A new world history. NY: LB Taurus

Sterling, Bruce. (1996). Holy fire. New York: Bantam Spectra.

von Daniken, E. (1969). Chariots of the Gods? Unsolved mysteries of the past. London: Souvenir.

Wright, Ronald. (2004). A short history of progress. Toronto: House of Anansi Press.