Section 2 : Southern Door ~ Learning with Open Heart and Mind

Chapter 10: Indigenous peoples in the 21st Century

Introduction

Before introducing the central topic of this chapter, Indigenous peoples in the 21st century, a few more words on Indigenous resurgence are worthy of sharing. The following excerpt comes from prominent Indigenous scholars. They position Indigenous resurgence and the ‘fight’ for self-determination in the context of unending tensions that exist for Indigenous peoples in a nation state trying to somehow rid itself of its imperialistic colonizing hegemony through words; but, nowhere near ready for the action necessary to decolonize itself and create real change. Coulthard, Manuel, Posluns, Deloria & Manuel explain,

“Over the past ten to fifteen years, Indigenous resurgence has emerged as a central theoretical framework in much Indigenous writings on colonization and decolonization. Resurgence calls on Indigenous people and communities to combat the violence of colonial social relations through the revitalization of Indigenous epistemologies, political structures, and place-based economic practices. As an ethicopolitical practice, resurgence demands that we decolonize “on our own terms,” to quote one of its core theorists, Nishnaabeg scholar and activist Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, “without the sanction, permission, or engagement of the state.”1 While theories of resurgence are at their core rooted in land and place, they also recognize that we are “intrinsically linked to and [are] influencing global phenomena; indeed, our systems of ethics require us to consider these influences and relationships in all of our decision making.”2 For Simpson, then, resurgence must be vigilantly global in scope, both ethically and politically” (Coulthard, Manuel, Posluns, Deloria & Manuel, 1974).

As seen at the end of the last chapter, the creation of Nunavut and moving its peoples into early stages of self-determination and self-governance within the existing parameters of territory within Canada has been an important step and a concrete example of Indigenous resurgence; but, the over-arching tensions are far from over.

So where does one begin to really understand Indigenous peoples in 21st century. There are so many aspects of ‘Indigenous’ life including on-going struggles, cultural reclamation, resurgence, and the ever-important resistance against measures that diminish them as peoples. It will take much more than this introductory course to examine these aspects. However, let me suggest a few immediate ideas of where to start.

The IKERAS Faculty has an array of Indigenous Knowledge Education (IKE) courses listed in the University’s Course Catalogue, in which you can immerse yourself and begin a journey of getting to know our Indigenous instructors, their connections to community, and correspondingly, Indigenous peoples including the three main cultural groups, First Nations, Inuit and Métis.

In the last two decades, there have been steady waves of Indigenous writers and storytellers, who bring their rich narrative to the mainstream public, and you can have a most unique glimpse into the lives of Indigenous peoples, past, present and future through their works. I just picked up a book the other day titled, Me Tomorrow: Indigenous Views on the Future (2021), edited by a prolific Indigenous writer, Drew Hayden Taylor, as lately I’ve been wanting to explore conceptions of time and futurism through an Indigenous lens. I couldn’t begin to list all the talented writers; but, I can point you to a good text to begin exploring some of those writers. It’s called An Anthology of Indigenous Literatures in English: Voices from Canada published by Oxford University Press in 2020.

A quick trip to UPEI’s Robertson Library and their Indigenous holdings will further your discovery. I mentioned in the last chapter, Indigenous Cinema that contains a treasure trove of film, documentaries, and shorts for your viewing. IKERAS has both an Indigenous literatures (IKE 2046) and Indigenous music, film, and arts (IKE 2042) course that will expose you to an array of works and lives.

Lastly, in the last chapter, I introduced you to an exceptionally well done CBC television series released in 2013 called the 8th Fire, narrated by now Manitoba Premier, Wab Kinew. Start with Episode 1: Indigenous in the City. The episode profiles several Indigenous peoples, and the episode is guaranteed to unapologetically confront any preconceived notions or stereotypes of who Indigenous people are in the minds of the misinformed.

Topics at a Glance

- Indigenous peoples in the 21st Century

- Inuit and Métis Nations

- Social Activism: Creating a New Narrative for Social Change

Indigenous peoples in the 21st Century

As you may have gathered by now, I enjoy photography. The use of digital images to capture people and events date back to the creation of the camera. I may have a piece I wrote about the history of photography when I was enrolled in the Photography Program at Holland College, Charlottetown, PEI in 2014-2016; but, I will forego that discussion in favour of focusing on the topic at hand. Though, the history of photography relating to Indigenous peoples and its digital exposition is significant.

The medium of photography, television, film, documentaries, and social media does play a role in informing about Indigenous peoples. The perceptions we form from these often stay with us for a long time. Sadly, certain stereotypes and caricatures can be one of those perceptions. I believe that images and/or narratives which have significant meaning and importance for respective cultures must be created by Indiegnous people themselves, or at the very least Indigenous-informed. Recall, Frideres spent considerable time explaining why the authors of history matter. The days of cultural appropriation must be put in the ‘rearview mirror’; and it’s time for Indigenous peoples to be in the driver seat of their own destiny. Again, we’ll leave further exploration of Indigenous self-determination, knowledge creation, and control over their own narrative for later.

In Figure 39, you will find images Elders, adults, and youth at gatherings and events. They no way represent the diverse cross-section of Indigenous peoples across Turtle Island nor how they live, work, and contribute daily to contemporary society. Nonetheless, they do capture Indigenous peoples I have known or encountered in my travels.

Figure: 39: Images of Indigenous peoples in the 21st Century

One of the most important features of Indigenous peoples in the 21st century is they are the fast-growing demographic in Canada. According to Frideres (2024), “…Indigenous growth shows the population grew by nearly 43 percent, with nearly half under the age of 25, compared to 28 per cent for the non-Indigenous population” (Frideres, 2024, p. 237). He further states, “projections of Indigenous population suggest they will make up nearly seven per cent of the Canadian population by 2041” (p. 237).

Beyond the population growth, most importantly, the number of Indigenous young adults attending post-secondary institutions has reached new levels. Figure 40 presents a photo of Simon Fraser University (SFU)’s Class of 2017 that included every level of degree including Bachelor, Master and PhD. My daughter, Morgan, obtained a BA Honours in Psychology at UPEI in 2012, then received her Master of Arts in Criminology from SFU located in British Columbia. She has been a Sessional Lecturer with the IKERAS Faculty since 2022.

Figure 40: Class of 2017 Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia

The same year, 2017, on this other end of the country at the University of Prince Edward Island, a record ten Indigenous students were awarded degrees in various faculties. What is also unique is that Elder Judy Clark, Abegweit First Nation, who was also UPEI’s long-standing Elder-in-Residence, was conferred an Honorary Doctor of Philosophy. It was a special year in higher education for the First peoples of Epekwitk along with other Indigenous students receiving their degree from the university. Figure 41 presents several images from that special Convocation Day in May of 2017.

Figure 41: Class of 2017, University of Prince Edward Island, Charlottetown, PEI

What do we know about trends in educational attainment and employment for Indigenous peoples?

According to Statistics Canada (2021), which undertook an examination of postsecondary educational attainment and labour market outcomes of Indigenous peoples through census data, “Indigenous people have made important gains in higher education from 2016 to 2021, with the share of Indigenous people holding a bachelor’s degree or higher increasing by 1.9 percentage points over that period. Increases were seen across all Indigenous groups, namely First Nations people, Métis and Inuit. This corresponded with better labour market outcomes compared to Indigenous people with lower levels of educational attainment“.

In the same reporting, Statistics Canada indicated that “during the 2021 Census reference week, from May 2 to May 8, 2021, 61.2% of Indigenous adults aged 25 to 64 years were employed, with the proportions varying across Indigenous groups: 56.6% among First Nations people, 68.8% for Métis, and 55.2% for Inuit. While these employment rates all fell below the rate recorded for the non-Indigenous population (74.1%), the gap narrowed with increasing levels of education” (Statistics Canada, 2021).

These two findings reveal that these two important social demographic attributes have important significance to Indigenous peoples’ integration into Canadian society; but as well are key determinants to their health and well-being. There is additional social demographic information that could be included such as age distributions, dependency ratios, and income; but, these are left for higher level courses such as IKE 2220: Indigenous peoples in Canada for further exploration.

The education and employment findings suggest we, as a country, are heading in a very direction with respect to Indigenous peoples whereas decades earlier there was a stark socio-economic trend that was heading in a completely different and disconcerting direction as compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts.

Frideres (2024) offers the following as contributing to an even more promising future,

“Two changes in Canadian society would make it possible to bring about social change that would integrate Indigenous peoples in mainstream society without having to assimilate: decentralization and Indigenous sovereignty. Indigenous peoples are demanding to have a say in the future of Canada, and a liberal democracy must take these concerns into account if it is to build a cohesive society. Change must fully involve Indigenous peoples. This is a two-sided process, and unilateral methods to invoke social change, whether imposed from the top down or welling up from the grassroots, are doomed to failure. New models of representing Indigenous peoples in the policy development process need to be established so that their aspirations can be included in the development of Canada” (Frideres, 2024, p. 261).

Indigenous Organizations

Before leaving our discussion on Indigenous peoples in the 21st century, I draw your attention to the nationally recognized Indigenous organizations which figure prominent in what Frideres termed ‘policy development’ and the consultation process on any issues or matters that impact Indigenous peoples. The ‘duty to consult’ is a legally binding concept that must be adhered to when making decisions that could affect Indigenous peoples and their communities.

Provided is a list with links of those national organizations:

- Assembly of First Nations

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami

- MétisNational Council

- National Association of Friendship Centres

- Native Women’s Association of Canada

- Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada

- Women of the MétisNation

Allyship

In the last decade, the terms ‘ally” and ‘allyship’ have been introduced to describe the role or action(s) that non-Indigenous peoples can take to acknowledge, support, and work with Indigenous peoples going forward especially in the advancing reconciliation. Below is a succinct video that explains these concepts further. I am a firm believer that allies are needed for this future to become a reality.

How to be a good ally? Naomi Bob – Indigenous Voices on Reconciliation

Another video that is highly appropriate to share at this point in our learning journey also speaks to the role others can take to support a future inclusive of Indigenous peoples. The speaker is very open about his life, and you will find that Indigenous peoples are quite willing to share their story as honesty, authenticity, and the lived reality are prerequisites for relational accountability to occur.

What non-Indigenous Canadians need to know

We will now turn our attention to further understanding two other nations that comprise Indigenous peoples in Canada – the Inuit and Métis Nations.

Inuit and Métis Nations

You likely have a good grasp on the Inuit having been introduced at various points in our learning journey to the peoples, their histories, and past and contemporary issues largely in Chapter 9. I begin by asking the basic question below to refocus our attention on the Inuit Nation.

Who are the Inuit?

In 2005, as a member of the Aboriginal Spiritual Journey delegation with Veterans Affairs Canada, which I spoke about earlier, I had the opportunity to meet several Inuit. In Figures 42, 43, and 44, I present two of our Inuit youth, an Inuit Elder, and members from the Inuit community, who unveiled an Inuksuk in Juno Beach in France.

Figure 42: Aboriginal Spiritual Journey Inuit Youth Delegates

Figure 43: Aboriginal Spiritual Journey Inuit Elder

Figure 44: Inuit community members unveiling an Inuksuk in Juno Beach in France.

The Aboriginal Spiritual Journey was a significant teaching, and a most humbling experience.

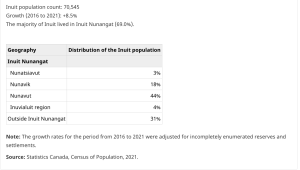

In Figure 45, you will find population data respecting the Inuit (Statistics Canada, 2021).

Figure 45: Statistical Description of the Inuit in Canada (2021)

The following two videos will give you further perspectives regarding the lives of the Inuit. The first video is an Inuit Elder, Rebecca Iquollag, on the “Inuit way”. The second is a short film showcase from National Geographic with the following description, “In Northeastern Canada, a traditional Inuit hunter, carver, and guide is watching the world change before his eyes. In Keeper of the Flame, Derrick Pottle shares the meaning behind the Inuit way of life and why he continues the traditions of his culture” (National Geographic, 2018).

The Inuit Way: Rebecca Iquollaq – Gjoa Haven Elder

Keeping the Inuit Way of Life Alive in a Changing World | Short Film Showcase

The IKERAS Faculty hopes to introduce more courses specific to the Inuit in the future. We will now examine the Métis Nation.

Who are the Métis?

According to the 2021 Census, 624,220 people who identified as Métis with 224,650 individuals reported being a registered member of a Métis organization or Settlement. Additional population data can be found at Statistics Canada.

I return to the work of Chelsea Vowel, who examines Métis identity in her book Indigenous Writes: A Guide to First Nations, Métis & Inuit Issues in Canada (2016). She states,

“It wasn’t until 2003 that the question, “Who really is Métis?’ got some serious attention. The Supreme Court of Canada heard a case involving a father and son who shot a moose out of season without a licence…The Powley Test, as it is known, set out basic criteria for determining who is accepted as Métis by the Canadian state. Here I am using the Métis Nation of Alberta’s summary of those criteria, which is pretty similar to what other regional Métis organizations have adopted and use to determine regional membership:

“Métis means a person who self-identifies as a Métis, is distinct from other aboriginal peoples, is of historic Métis Nation ancestry, and is accepted by the Métis Nation” (p. 41). Despite being overly broad, it did accomplish one thing, that being, the concept of the community, in this case, the Métis Nation, making the determination who is a member of their community. This may be another application of the concept of self-determination, and the right for the nation to determine who is part of their community and who is not.

In 2016, the Supreme Court of Canada released the Daniels decision, which made the determination that “Indians” as defined by section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 included Indians (status and non-status alike), Inuit, and Métis (Vowel, 2016, p. 49). There are further details and implications; but, know that the Daniels decision is still being worked through in every respect from the federal government responsibility to program and services provided to Métis peoples through organizations representing both Métis and off-reserve Indigenous peoples. It is quite complex.

Let us turn to the following video, which covers the information above quite succinctly; but, also highlights the controversy that a ‘mixed’ heritage can bring in different parts of Canada.

My first clear recollection of being introduced to Métis peoples came in 2005 when involved in the Aboriginal Spiritual Journey: Calling Home Ceremony with Veterans Affairs Canada. Figure 46 shows the young Métis singer-songwriter, and fiddle player, Sierra Noble, her mother, Sherry Noble, and the former National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations, Chief Phil Fontaine. You may sample some of Sierra’s work by following the embedded links in text.

Figure 46: Métis musician Sierra Noble, Sherry Noble, and Chief Phil Fontaine (2005)

Figure 47 shows a group of Métis traditional dancers, who were also part of the Aboriginal Spiritual Journey. The traditional music and dance of Métis peoples is quite distinct and distinguishable from other Indigenous groups.

Figure 47: Metis cultural performers in Juno Beach, France (2005)

Please take note of the Métis sash that is worn by both Sierra and the cultural performers. The Métis sash is described as follows:

“The Métis sash is a colourful finger-woven belt that is usually three-meters long. It is sometimes referred to as L’Assomption sash or Ceinture Fléchée (arrow sash). The sash was used by the Voyageurs of the fur trade and was quickly adopted by their Métis sons. They used the sash as a belt to hold coats closed, and, also as a towrope, tumpline, towel, and even a sewing kit. The Métis sash became the most recognizable part of the Métis dress and a symbol of the Métis people. Today, the sash continues to be an integral part of Métis culture and heritage” (Métis Nation of Alberta, 2024). The sash is but one of the distinctive symbols of Métis culture with the other described on the site.

As indicated earlier, one of the national organizations representing Métis Nations and their peoples is the Métis National Council. I invite you to learn more by visiting their website, which will link you to important learning resources. In the future, the Faculty plans to introduce specific courses relating to the Métis. We have several Métis members on Faculty, and if I have not pointed this out before, please visit the Elders and Scholars profile page.

Let us now look at the final topic of this chapter, Social Activism: Creating a New Narrative for Social Change.

Social Activism: Creating a New Narrative for Social Change

What is social activism, anyway? When you think of social activism, what are the first things that come to mind? Does Figure 48 correspond with your image of social activism?

Figure 48: Climate Emergency March, Charlottetown, PEI (2019)

So, what is social activism? Is it…

- fighting for social rights?

- actively protesting injustice?

- a collective social movement to enact or bring about change?

What are the characteristics of ‘activists’ or the features of ‘activism’? Which attributes, either positive or negative, are linked to either or both terms? Please make your list and let’s compare.

I did a quick scan of the literature using the two key words and included the word ‘stereotype’. While the latter is suggestive of preconceived notion of what we tend to think, I wanted to get a sense of what the literature tells us. Below are some of the words (stereotypes) associated with the terms with the authors who published scholarly articles on various aspects of the topic in brackets.

- marginalized and racialized (Anyiwo, Palmer, Garrett, Starck, & Hope, 2020)

- eccentric and militant (Bashir, Lockwood, Chasteen, Nadolny, & Noyes, 2013)

- tree-hugger, hippie, over-reactive (Bashir et al., 2013)

- unpleasant extremists (Sobieraj, 2011)

- feminists, aggressive, unconventional and disagreeable (Berryman-Fink & Verderber, 1985; Twenge & Zucker, 1991; Dutt & Grabe, 2014)

- radical, aggressive emotionality, moral superiority, virtue-signaling (Phelan, 2019)

- disadvantaged, strong, and aggressive (Burrows, Selvanathan, & Lickel, 2023)

- raging grannies (Sawchuk, 2009)

How do your perceptions and those above compare? An interesting study on activism and identity by Mannarini, Fedi, & Pozzi (2024) examined the perceptions of young activists themselves. The study is explained this way,

“Identity is considered a key factor in activist engagement. In this study, we examined the self-representations of a group of young activists through the lens of the ego-ecological approach, which emphasizes the interplay of representations, attitudes, and beliefs (including stereotypes) that circulate both within groups and in the broader sociocultural environment in identity formation” (Mannarini, Fedi, & Pozzi, 2024).

Interestingly, the authors reported that “our young participants’ self-representations portrayed activists as determined, passionate, strong, competent, cohesive, receptive to ideas and needs, warm and supportive people, all positive characteristics attributed to the self, which resonate with the stereotypical notion of the “good activist” (Mannarini, Fedi, & Pozzi, 2024).

In a further review, Anyiwo, Palmer, Garrett, Starck, & Hope (2020) examined the sociopolitical action of racially marginalized youth. Based on their review of the literature, they found that the ‘nature of sociopolitical action’ comprises the following,

“Youth’s individual sociopolitical action can occur through conventional politics and community engagement such as writing letters to political officials about sociopolitical concerns, voting, giving opinions to media outlets, and volunteering [1,4,9]. Through interpersonal resistance, youth may reprimand friends, adults, or strangers who make racist comments and defend those who are racially targeted [10••,11,12]. Political engagement and resistance can also manifest in subtle, every day, and seemingly mundane strategies youth use to express themselves and survive [13] such as wearing clothing with cultural and political messages [14••], and academically persisting to contest social stereotypes [15,16,17•,18].

Collectively, youth sociopolitical actions manifest across multiple domains including joining political parties and campaigning [4,19,20], organizing to address systemic inequity [2,5,21,22,23••,24], and protesting (e.g., boycotting, blocking traffic, occupying buildings, marching) [4,6,19,25,26]. Organizing is a collective engagement practice that helps to bring together groups to advocate for resources and shape the policies and decisions made within social structures [2,23••]. Organizing provides an entree for youth to demand racially just institutional change from schools [27], a space that engenders the ability to work collaboratively with peers towards sociopolitical action [3,24], and a context to receive intergenerational care that helps to cultivate more activism [7,23••]. Protesting provides space for youth to assert their voices and advocate for social justice [4,19,25,26]. For example, racially marginalized youth describe protesting with family, peers, and teachers to advocate for educational equity, engaging in ‘die-ins’ to protest police brutality, and participating in marches to advocate for immigration reform [11,16,17•].

Racially marginalized youth use digital media (e.g., online videos, blogs, social media) to build a sense of community, share their stories, and access a larger audience for their social justice efforts [5,25,26,28,29•,30]. For example, Black youth use social media hashtags (#BlackLivesMatter, #IfTheyGunnedMeDown) to facilitate dialogue about racial injustice, such as the murders of Black people by police, and to challenge stereotypical, hegemonic depictions of Black people in mainstream media [6,28,30,31]. Similarly, Latinx youth use social media to provide counter narratives to racialized and anti-immigrant discourse and to advocate for the rights of undocumented youth [31,32]” (Anyiwo, Palmer, Garrett, Starck, & Hope, 2020).

While their examination was focused on sociopolitical action in the United States, the authors imply other nation states may be ‘sites’ of action as indicated in the following quote,

“Nations with a history of racial stratification, such as the United States, have enacted policies and practices that sustain white dominance and the marginality of non-white racial groups. However, racially marginalized youth’s resistance has been instrumental in promoting societal change aimed toward dismantling this dominance” (Anyiwo, Palmer, Garrett, Starck, & Hope, 2020).

What about Indigenous social activism? What about Indigenous social activism in Canada? Before examining this topic, I present one other aspect of activism that is worthy to consider.

What did this webpage reveal about people known for activism? Did you recognize any names? Would any of these individuals be characterized as ‘unpleasant extremists’, ‘aggressive’, or ‘over-reactive’, borrowing from our previous descriptions.

Did their efforts bring about substantial attention to or societal change? What change occurred because of their ‘activism’?

You will note several Indigenous individuals on that list.

Indigenous leader, Arthur Manuel, who you were introduced to in an earlier chapter, asserts that the rise of two significant Indigenous activist movements, ‘Defenders of the Land’ and ‘Idle No More’ as a grassroots struggle is the result of inaction by the colonial power and structures. He states,

“…the Defenders and Idle No More are the basis for building a movement in Canada. No one else will play this role except us, and we can build on the considerable discontent floating around in communities.

Even with Justin Trudeau’s charm offensive, people see that things are not adding up. One thing is promised but another is delivered. We have seen again and again that the prime minister and premiers are not interested in giving up one inch of power to Indigenous peoples, and Prime Minister Justin is no exception. You are daydreaming if you think you can negotiate your way to freedom without creating tension to push our colonizers to decolonize Canada” (Manuel, A., 2017, p. 30).

In the article by Kanahus Manuel, Decolonization: The frontline struggle, which was your ‘homework’, I found her personal account as very important to understand why an Indigenous mother would risk going to jail for her ‘activism’. She recalls,

“When I was arrested, I was in a truck with my three-month old child, my sister and my mother in the hills above Bella Coola. In the web of charges, they threw at me, the one that finally stuck was for “assaulting police,” a charge that had been levelled against many of us who were, in fact, assaulted by the police when we were trying to protect our land from the Sun Peaks development. I remember this as the saddest moment of my life. Not because I was going to jail but because I realized that while I was away, I would be separated from my infant son…. But I survived this ordeal because by then I already knew who I was and what I had to do as a Secwepemc woman to fight for my people. This was the period where my own mind was being decolonized” (Manuel, K., 2017, p. 43).

Like Kanahus, there are many other Indigenous women activists in Canada, who felt it their obligation to ‘defend’ and not sit ‘idly’ by when such pressing matters such as the “environment, Indigenous and treaty rights, equal access to education and health care, and the rights of women and children” needed action. These include such names as Bertha Clark Jones, Autumn Peltier, and Cindy Blackstock, to name just a few (Boyko, 2022).

The Government of Canada has dedicated a webpage to celebrate National Indigenous History Month, and a special feature of this site is the contributions of those deemed Indigenous trailblazers. Please take a moment to learn about these inspiring Indigenous peoples, who represent many areas such as the arts, sports, scientists and researchers, and activists and advocates (Government of Canada, 2024).

One globally recognized Indigenous activist, author, lawyer, and Mi’kmaq (Eel River Bar First Nation, NB) is Pam Palmater. Her seminal 2015 publication, Indigenous nationhood: Empowering grassroots citizens, is an excellent read for understanding what it will take to achieve nationhood through mobilizing community. Let us take a minute to listen to her views on activism. There is also a message about what non-Indigenous peoples can do around the issues.

Dr. Pamela Palmater is an advocate for Indigenous issues

What were her main points for non-Indigenous peoples in Canada?

I turn my attention closer to Epekwitk, and an Indigenous social activism movement in which I participated. It was the 2013 national Idle No More, which “diminished the rights and authority of Indigenous communities while making it easier for governments and businesses to push through projects without strict environmental assessment” (de Bruin, 2013). See Figure 49 with an accompanying video for the Charlottetown Protest.

Figure 49: Idle no More, Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island (2013)

Following the event, I gave a special ‘Teach-in’ at the university for faculty, staff and students as many did not know what this social movement was about. I think this was the very first time as an academic, even though I was still part-time, that I had addressed the broader university community on Indigenous issues.

Several years later, another movement, Black Lives Matter, a social justice activism movement, took hold beginning in the United States and spreading globally, and is described in this way,

“The movement seeks to attain racial justice for African-Americans and those who identify as black. Activists who participate in the movement aim to bring an end to violence and systemic racism aimed against black people. Since its inception as a hashtag, it has transformed into a full-fledged movement that manifests on and offline, and it has expanded from being a response to police brutality to encompassing all types on injustices faced by black people, including in the realms of education, the criminal justice system, and class relations” (Open Case Studies, UBC, 2024).

Like Black Lives Matter, it was not long before Indigenous Lives Matter came to be. Already propelled by decades of injustice and inaction, and the collective will to stand up to oppression following Idle No More, it wasn’t long before Indigenous peoples rose once more. Figure 50 presents a series of images from the Indigenous Lives Matter March in 2020 (Figure 50)

Figure 50: Indigenous Lives Matter in Charlottetown, PEI (2020)

There is a site that details the history of the Indigenous Lives Matter movement and a description of current Indigenous social activist movements in Canada, which bring attention to issues of injustice and systemic racism, a term we learned about in chapter six. Please visit Stand in Solidarity: Movements Declaring that Indigenous Lives Matter.

This important topic would take an entire course to do it ‘justice’. In fact, the IKERAS Faculty will be launching a specific course titled IKE 2052: Indigenous Resistance and the Work of Decolonization in the Spring 2024 semester that will examine resistance and decolonization movements in greater detail. But, before leaving this section and chapter, here is a quick video that, in my mind, says it all.

Indigenous Canadian water activist addresses UN

- How did that make you feel?

My question, the one that has been on my mind for well over a decade, the one I have presented on in many courses I have taught, the one that prompted me to join several grassroots movements, and the one I think about when I consider our decisions of today will have impacts seven generation from now including inaction. The question is a simple one:

Can we sit idly by as our world and life as we know it is in peril?

Key Terms and Concepts from Chapter

- Self-directed

Important Readings / Viewings for Next Class

Senator Murray Sinclair Article – A Manual for Decolonization (pp. 68-72)

Special Topics of Interest

Learning resources about First Nations, Inuit and Métis across Canada

Taiaiake Alfred on It’s All About the Land

Cultural Competency Supplemental Tutorials

End Notes

- Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, Dancing on Our Turtle’s Back: Stories of Nishnaaneg Recreation, Resurgence, and a New Emergence (Winnipeg: Arbeiter Ring Press, 2011), 17.

- Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), 56.

References

Anyiwo, N., Palmer, G. J., Garrett, J. M., Starck, J. G., & Hope, E. C. (2020). Racial and political resistance: An examination of the sociopolitical action of racially marginalized youth. Current opinion in psychology, 35, 86-91.

Bashir, N. Y., Lockwood, P., Chasteen, A. L., Nadolny, D., & Noyes, I. (2013). The ironic impact of activists: Negative stereotypes reduce social change influence. European Journal of Social Psychology, 43(7), 614-626.

Berryman-Fink, C., & Verderber, K. S. (1985). Attributions of the term feminist: A factor analytic development of a measuring instrument. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 9(1), 51–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1985.tb00860.x

Burrows, B., Selvanathan, H. P., & Lickel, B. (2023). My Fight or Yours: Stereotypes of Activists From Advantaged and Disadvantaged Groups. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 49(1), 110-124. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672211060124

Coulthard, G. S., Manuel, G., Posluns, M., Deloria, V., & Manuel, D. (1974). Introduction: A Fourth World Resurgent. In The Fourth World: An Indian Reality (pp. ix–xxxvi). University of Minnesota Press. https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctvf34hsb.3

Dutt, A., & Grabe, S. (2014). Lifetime activism, marginality, and psychology: Narratives of lifelong feminist activists committed to social change. Qualitative Psychology, 1(2), 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000010

Frideres, J. (2024). Indigenous Peoples in the Twenty-First Century. 4th Edition. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

Mannarini, T., Fedi, A., & Pozzi, M. (2024). “We, activists”, “They, the activists”: Exploring Activist Identity Among Youth Inside and Outside the Stereotype. Identity, 24(2), 156–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2024.2315441

Manual, A. (2017). The Grassroots Struggle: Defenders of the Land & Idle No More. McFarlane, P., & Schabus, N. (Eds.) in Whose land is it anyway? A manual for decolonization.

Manuel, G., Posluns, M., & Deloria, V. (1974). The Fourth World: An Indian Reality. University of Minnesota Press. https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctvf34hsb

Manual, K. (2017). Decolonization: The Frontline Struggle. McFarlane, P., & Schabus, N. (Eds.) in Whose land is it anyway? A manual for decolonization.

Palmater, P. (2015). Indigenous nationhood: Empowering grassroots citizens. Fernwood Publishing.

Phelan S. (2019). Neoliberalism, the far right, and the disparaging of “Social Justice Warriors.” Communication, Culture & Critique, 12(4), 454-475. https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcz040

Sawchuk, D. (2009). The Raging Grannies: Defying Stereotypes and Embracing Aging Through Activism. Journal of Women & Aging, 21(3), 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952840903054898

Simpson, L. B. (2011). Dancing on our turtle’s back: Stories of Nishnaabeg re-creation, resurgence and a new emergence. Winnipeg, MB, Canada: Arbeiter Ring Pub..

Sobieraj, S. (2011). Soundbitten: The perils of media-centered political activism. NYU Press.

Ruffo, A. G., Vermette, K., Moses, D. D., & Goldie, T. (Eds.). (2020). An Anthology of Indigenous Literatures in English: Voices from Canada. Oxford University Press.

Twenge, J. M., & Zucker, A. N. (1991). What is a feminist? Evaluations and stereotypes in closed- and open-ended responses. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 23(3), 591–605. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1999.tb00383.x

Vowel, C. (2016). Indigenous writes: a guide to First Nations, Metis, & Inuit issues in Canada. Portage & Main Press.