Reading Resources

Selected Readings from Whose Land is it Anyway? A Manual for Decolonization: Part I

THE MACHINERY OF COLONIZATION

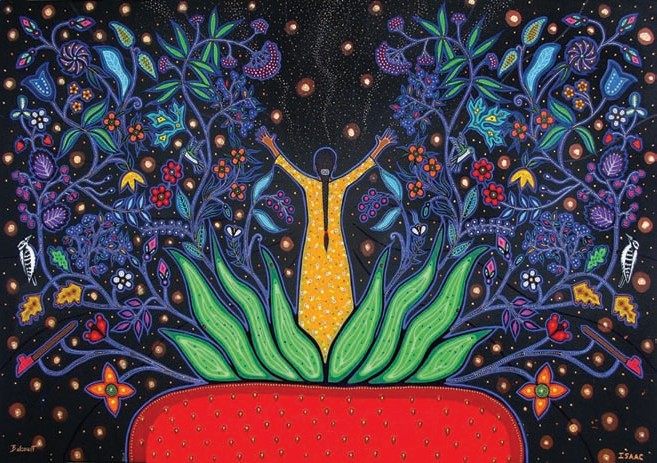

Christi Belcourt & Isaac Murdoch

It’s all about the land

Taiaiake Alfred

For many generations we Indigenous people have been in a life and death struggle for survival, for respect of our humanity, restoration of our nationhood, and recognition of our rights. This whole time, a constant surge of ancestral memory running through our veins has empowered and enlivened us and given us the gifts of tenacity, anger, patience and love, so that the people may continue and so that the generations that are yet to rise from the earth may know themselves as the real people of their land. The voices of our ancestors continue to call out to us, telling us that it is all about the land: always has been and always will be… get it back, go back to it. We have fought for the land and for our connection to it. For five hundred years, it is this struggle to restore the living relationship between our ancestors, our land and ourselves that has defined us as Indigenous people, and it is this struggle that has ensured our survival in the face of ignorance and violence.

Now that we have proven that we will not accept annihilation, we find ourselves in an era of reconciliation. Reconciliation? Like many of my sisters and brothers, I have trouble understanding what it is that we are trying to reconcile. Is the time for fighting over? Have we come through to the other side of the nightmare that is history? Have we decolonized this country? Reconciliation: the invitation from Canada to share in the spoils of our nations’ subjugation and dispossession. What a tainted gift, and such a false promise. Reconciling with colonialism cannot heal the wounds the colonizers have wrought on our collective existence. The essential harm of colonization is that the living relationship between our people and our land has been severed. By fraud, abuse, violence and sheer force of numbers, white society has forced us into the situation of being refugees and trespassers in our own homelands and we are prevented from maintaining the physical, spiritual and cultural relationships necessary for our continuation as nations.

Our struggle is far from over. If anything, the need for vigilant consciousness as Indigenous people is stronger than ever. Reconciliation is recolonization because it is allowing the colonizer to hold on to his attitudes and mentality, and does not challenge his behaviour towards our people or the land. It is recolonization because it is telling Indigenous children that the problem of history is fixed. And yet they know through life experience that things have not changed and are getting worse, so they must conclude I am the problem.

If reconciliation is allowed to reign, our young people are going to bear the brunt of this recolonization and carry a tension inside of them that is very difficult if not impossible to live with – indeed we are already seeing the sickening results of this psychological war on our young people in the shocking and recurring waves of self-harm and suicide that affiict every one of our communities.

When you are told that you are Indigenous, that this is your land, that you have a spiritual connection to this place and that your honour, health and existence depend on your relationships with that river, those animals, those plants, when you are told that this is the right and good way to live and you are held to account for that culturally and spiritually, and you’re not able or allowed to live out any of that… What happens to a person, a spirit, a mind? What emerges is not peace, power and righteousness but a mass psychopathology characterized by discordant identities, alienated personalities, and worst of all a culture of lateral violence fueled by unresolvable self-hatred. Sadly, this is becoming typical among Indigenous people, and typical I think of the societal reality that will form in the era of reconciliation.

Reconciliation’s purported gifts can do nothing but make things worse because, paradoxically, educated people experience these soul illnesses even more than others. The educated person knows even more surely than everyone else that there is no way out of this colonially diseased dynamic. There really is no way to decolonize from within the recon- ciliation paradigm. There is no way, except to get out: a resurgence of authentic land-based Indigeneity. Our youth must be shown that they have the power to resolve the basic anxieties and psychological discords affiicting them by recognizing and respecting the powerful gifts that are there in their ancestral memory. The way to fight colonization is by reculturing yourself and by recentring yourself in your homeland.

Does anyone remember the report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples? So much work went into that document, from all across the country and taking into account the perspectives and voices of all regions, generations and segments of our Indigenous peoples. From 1992 to 1996, a heady time when the legal and political phase of our peoples’ struggle was at its peak, the voices of our ancestors came through in the wisdom spoken to the Commission through our clan mothers, chiefs and youth. What they told the Commission in a unified voice was that it’s all about the land. In a rare show of integrity and respect on the part of government, the commissioners listened and the voices of our ancestors echoed in the multiple volumes of the Commission’s lengthy and comprehensive report when they stated clearly and emphatically that what is needed to achieve the full decolonization of Canada is a massive transfer of land back to the Indigenous peoples. The need to restore our lands to our nations was true in1996 and it continues to be true today. A notion of reconciliation that rearranges political orders, reforms legalities and promotes economics is still colonial unless and until it centres our relationship to the land. Without a return of land to our nations and comprehensive financial support for Indigenous youth to reclaim, rename and reoccupy their homelands, to do what they need to do to ensure their own and coming generations’ survival as real people, reconciliation is recolonization.

The voices of our ancestors still call out to us and their wisdom still flows through our veins. We just need to start listening to them: It’s all about the land.

Taiaiake Alfred (PhD—Cornell University) is an author, educator and activist from Kahnawake and internationally recognized Kanien’kehaka professor at the University of Victoria. He was the founding director of the Indigenous Governance Program and was awarded a Canada Research Chair 2003–2007, in addition to a National Aboriginal Achievement Award in education. He is the author of Wasáse: Indigenous Pathways of Action and Freedom, Peace, Power, Righteousness: an Indigenous Manifesto, and Heeding the Voices of Our Ancestors.

Crown title : A legal lie

Sharon Venne

Red Rising Magazine

Most Canadians assume that somehow Canada acquired formal title to this land 150 years ago in the British North America Act, the country’s founding document. That this is not the case is clearly reflected in the fact that Canada is still desperately negotiating with hundreds of First Nations to have them surrender, once and for all, their title to the lands given to us by the Creator.

So, it is clear even today that Canada and the provinces that were created by an Act of the British Parliament in 1867 do not have any inherent authority in our territories. In the creation of the state, the lie of underlying title was passed along without much thought to the implications. Or, if the British House of Commons or Lords thought of the implications, there was a decision made at some point to try to simply disinherit the rights of our nations.

We see the continuation of these same legal lies today in the so-called British Columbia treaty process, which is clearly a sham process. It is not a treaty process. It is not dealing with the real issues of underlying title. The land claims policy of Canada works from the assumption that the title vests in the Crown and that the Indians are making a “claim” for our own lands and territories.

The British used the Doctrine of Discovery to assert authority and jurisdiction over our territories throughout Turtle Island. It was to prevent other colonizers from asserting their jurisdiction. The British Crown sent representatives across the oceans to the shore of our island. What they saw, they wanted. There was only one problem. The lands and resources were being used by our nations. In order to gain access to our territories, the British Crown enacted the Royal Proclamation of 1763 to govern the subjects. This Proclamation was for the subjects of the Crown to follow when trying to access our territories. There are three important aspects of the Royal Proclamation: 1) In order to access the lands and territories of “Indian Nations or Tribes,” there needed to be an agreement or a treaty. 2) If the Crown’s subjects were within the territories of the Indian Nations or Tribes, the Crown was obligated to remove them (they would be considered squatters). 3) Agreements or treaties would be made only if the Indians “so desired.” This makes treaties a prerequisite to the Crown’s subjects legitimately moving into the territories of Indigenous Nations.

There was a start to the treaty-making process that moved from the east going west and north; when the colonizers reached the Rocky Mountains, they stopped making treaties with our nations.

Except for the treaties made on Vancouver Island and a small section of the northeastern part of what is now called British Columbia, the rest of the present province remains without the treaties that were demanded by the directives of the British Crown.

In 1972, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) – which some people refer to as the World Court – issued an advisory opinion in relation to the rights of Indigenous peoples in the Western Sahara case. The Court struck down the concepts of discovery, conquest and terra nullius – lands without any people. Our nations were never discovered; we were not lost. We were not conquered. Our territories were not terra nullius – the ICJ directed that there needed to be a treaty prior to entering into their territory. British Columbia and large areas of Canada did not have treaties with the colonizers. Instead, Canada tries to manipulate the treaty process. The policies leave our nations in debt as our small underfunded communities need to borrow money to have the resources to negotiate with Canada. The irony of the whole process is not lost on our old people – “Why are we borrowing money to talk about our lands?” Then, there are the non-ending unilateral decisions by Canada while it changes the non-ending policies and directives. Canada makes no attempt to have a true treaty relationship based on trust and good faith. It is one-sided. It is also contrary to the United Nations’ directives.

This was clear in Canada’s creation of the federal Comprehensive Land Claims Policy in 1986. This is a policy. It is not a law. It is not based on the elements of the Royal Proclamation of 1763. Canada continues to seek certainty largely through a de facto extinguishment of Aboriginal title. Most of the recent settlements contain a clause: “This Agreement constitutes the full and final settlement in respect of the aboriginal rights, including aboriginal title, in Canada of X First Nation.” If our nations did not have title, why does the state spend so much money and time to get the nations to sign off on the extinguishment clauses of a claims settlement?

There is no attempt by Canada to seek co-existence as set out in the Royal Proclamation, which recognized our nations and tribes as having ownership to our lands and the need for a treaty to access them. What is so hard to understand? Ownership would eliminate poverty. It would raise up our nations to their rightful place in the family of nations. Clearly, the state of Canada has a vested interest in maintaining the lie.

Sharon Venne, a lawyer and member of the Cree Nation who has worked on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and with First Nations communities on the implementation of their own legal systems. She has played an active role in the national and international struggles of many Indigenous peoples, including the Lubicon Cree and Dene Nation. She has a Masters of Law degree from the University of Alberta, and is presently a doctoral candidate, writing a thesis on treaty rights of Indigenous peoples and international law.

From dispossession to dependency

Arthur Manuel

Gord Hill

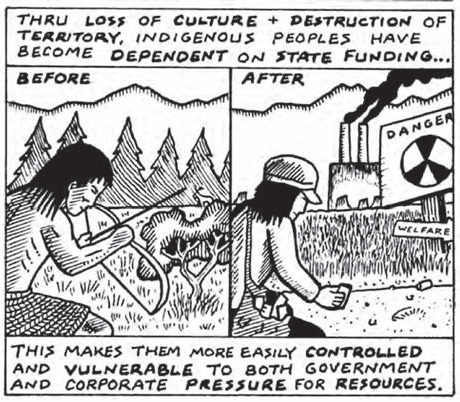

Colonialism has three components: dispossession, dependence and oppression. Indigenous people live with these forces every day of their lives.

I began with dispossession: our lands were stolen out from underneath us. The next step was to ensure that we are made entirely dependent on the interlopers so they can control every aspect of our lives and ensure we are not able to rise up to seize back our lands. To do this, they strip us of our ability to provide for ourselves.

This was done by trying to cut us off from access to our land. My father, in his book The Fourth World, wrote how this was achieved in the BC Interior by literally fencing us off from our lands. Suddenly, our hunting grounds, our fishing spots, our berry patches and other gathering places were cut off by fences and then enforced by a maze of regulations, while our timber was carted away and our lands stripped of our minerals. This had never even been envisioned by our people.

Even when we allowed the newcomers to set up settlements on our land, it was unthinkable that suddenly our lands would be closed to us.

We were suddenly corralled onto reserves under the authority of an Indian agent and given a few gardening tools for sustenance. In some areas, where the land was particularly fertile and the Indigenous peoples managed to generate small surpluses and tried to sell them, local white farmers complained about the competition and laws were passed forbidding us from selling our produce. It is important to note that our poverty is not a by-product of domination but an essential element of it.

But of course, it was not easy to keep us off our land. In my grandparents’ time, there was no welfare. Our people still survived by returning to land in stealth, fishing, hunting, picking berries and then working seasonally as farm labour, as ranch hands or in the woods. We had to find ways to make money all year round and to gather a significant portion of our food from our lands surrounding the reserve.

Welfare was introduced quite late, and again its main purpose seemed to be to keep us corralled on our reserves. When it was first introduced, people were actually reluctant to take it. The Indian agent came and said the government was going to give us “relief money” and our people were instantly suspicious.

There was a big debate on the reserve about whether we should accept it or not. People tried to understand why the white man would offer to give us this and no one could figure it out. That was when I was young. People were always trying to figure out what the white man was thinking, and we never could. It was always a very delicate situation with the white man. You would listen to what they said but what they said often made no sense at all. I remember people coming to see my father to ask if they should take the relief money. Because he worked on the river for the lumber company, my father had more contact with the white man, so people would always ask him what he thought. He told them that if they needed it, they should take it. The logic was that it was due to us because they had fenced off our lands from us and pushed us up against the river on the tiny reserve. But for my father, it was never more than a stopgap measure. He devoted his life to trying to get back our land and our right to govern ourselves.

In the immediate term, welfare cheques would play an important pacification role. It meant our people spent less time on our land and it allowed the white man to bring in all sorts of new laws forbidding us from hunting and fishing and trapping on our territories. When these measures were put in place, the Canada we see today was finally created. Indigenous peoples, from enjoying 100% of the landmass, were reduced by the settlers to a tiny patchwork of reserves that consisted of only 0.2% of the landmass of Canada, the territory of our existing reserves, with the settlers claiming 99.8% for themselves.

This is, in simple acreage, the biggest land theft in the history of man- kind. This massive land dispossession and resultant dependency is not only a humiliation and an instant impoverishment, it has devastated our social, political, economic, cultural and spiritual life. We continue to pay for it every day in grinding poverty, broken social relations and too often in life-ending despair.

But that was always part of the plan. We were left isolated and hungry while our land generated fabulous revenues from the lumber, minerals, oil and gas and agricultural produce. We were to be kept penned in on our 0.2% reserves until we were starved out and drifted onto skid row in the city and gradually disappeared as peoples.

Our dependency was not some accident of history. It is at the heart of the colonial system. Our poverty is not an accident, the result of our incompetence or bad luck; it is intentional and systematic. The brilliance of the Canadian system as it has evolved is that today our poverty and misery are actually administered by our own people. In a spirit that seems profoundly insulting, this system is even called by some “self-government.” Self-government as designed by the Canadian government is a system where we administer our own poverty.

The dependency built into this system can be heartbreaking. I once even heard a young person on the reserve saying that she could not wait until she was eligible to receive her own welfare cheques. That is how bleak their future is. That is all they had to hope for in life. Their own welfare cheque.

That is what colonialism leads to: complete and utter dependency. When this is the best they can hope for, it is not surprising that the suicide rate among our young people is among the highest in the world.

We cannot can solve these problems with a new program or new services administered from Ottawa or by Ottawa’s agents in our communities. Or by giving us hugs or tearing up when you speak of our misery. There is only one program to solve this dependency and despair, and that is to get rid of the deadening weight of the colonialism that causes it. For us to once again have access to our land and for the settlers to recognize at last our Creator-given title to it.

Arthur Manuel was one of the giants of the Indigenous movement within Canada and internationally. He served as chief of his Neskonlith Indian band and chairman of the Shuswap Nation Tribal Council as well as co-chair of the North American and Global Indigenous Caucus at the U.N. Permanent Forum on Indigenous Peoples. He was also co-author, along with Grand Chief Ronald Derrickson, of the award-winning book Unsettling Canada: A National Wake-up Call. Arthur Manuel passed away in January 2017. Lorimer Press published his second book, co-authored with Grand Chief Derrickson, in the fall of 2017.

The Indian Act –The foundation of colonialism in Canada

Russell Diabo

July 1901. Treaty Time, Little Forks, Rainy River. Photo MB Archives

The machinery of oppression in Canada has remained depressingly familiar for 150 years. From the pre-Confederation era until today, the Indian Act remains the foundation of Canadian colonization of Indigenous peoples. Although it has been amended numerous times since it was adopted in 1876, in the twenty-first century the Indian Act still maintains the main tenets of protection, control and civilization (meaning assimilation).

The Interpretation section 2.1 of the Indian Act provides key definitions of “Indians,” “band,” band list,” “council of the band,” “Indian moneys,” Indian Register,” “member of a band,” “reserve” and other terms used by Ottawa bureaucrats and politicians for colonial regulations and policy. Section 2.1 (c) authorizes the federal cabinet to create new “bands,” such as the Qalipu band recently created in Newfoundland.

The Indian Act was the original termination plan adopted by the Canadian Parliament over 140 years ago to break up Indigenous Nations into bands, setting Indian reserves apart, keeping a registry of Indians until assimilation is complete as individual “Indians within the meaning of the Indian Act” and “Indian bands” respectively become a collection of Canadian citizens living within municipalities without any legal distinctions from the general Canadian population. They would become “Indigenous-Canadians,” an ethnic group among others in the Canadian mosaic without any more rights of standing than Italian- Canadians or Ukrainian-Canadians.

Elimination of Indigenous Nations as distinct political and social entities was the ultimate objective of Indian Affairs policy. In a 1920 speech to a Special Committee of the House of Commons, Deputy Superintendent General Duncan Campbell Scott said bluntly:

“I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that this country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are able to stand alone. . . Our object is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department” (NAC RG10 Vol. 6180 File 470-2-3 Vol. 7: Evidence of DC Scott to the Special Committee of the House of Commons examining the Indian Act amendments of 1920, pp. 55, 63).

1969 White Paper on Indian Policy

In 1969, about a hundred years after the Indian Act was adopted, Liberal prime minister Pierre Trudeau and his minister of Indian Affairs, Jean Chrétien, believed assimilation of Indians had largely been completed and introduced a White Paper on Indian Policy to argue that special Indian rights were the problem and equality under the law was the solution. The 1969 White Paper proposed these policy objectives:

- Eliminate Indian status.

- Dissolve the Department of Indian Affairs within five years.

- Abolish the Indian Act and remove section 91.24 (“Indians and lands reserved for the Indians”) in the BNA Act.

- Convert reserve land to private property that can be sold by the band or its members.

- Transfer responsibility for Indian Affairs from the federal government to the provinces and integrate these services into those provided to other Canadian citizens.

- Appoint a commissioner to gradually terminate existing treaties.

The White Paper provoked widespread protest by Indians and responses in position papers like the Indian Association of Alberta’s Red Paper and the Manitoba Indian Brotherhood’s Brown Paper.

The modern Indian rights movement to protect and advance Inherent, Aboriginal and Treaty Rights was born, and regional Indian political advocacy organizations formed across Canada under the umbrella of the National Indian Brotherhood, which in 1982 became the Assembly of First Nations.

As First Nations galvanized across Canada to fight the Pierre Trudeau Liberal government’s proposed 1969 White Paper termination policy, the federal government was forced to consider a strategy on how to calm the Indian storm of protest by publicly agreeing to withdraw the proposal, while continuing to implement it through federal policy and programs.

In a memo dated April 1, 1970, David Munro, an assistant deputy minister of Indian Affairs on Indian Consultation and Negotiations, advised his political masters Jean Chrétien and Pierre Trudeau as follows:

“We can still believe with just as much strength and sincerity that the [White Paper] policies we propose are the right ones . . . The final [White Paper] proposal, which is for the elimination of special status in legislation, must be relegated far into the future . . . We should put varying degrees of emphasis on its several components and we should try to discuss it in terms of its components rather than as a whole . . . We should adopt somewhat different tactics in relation to the [White Paper] policy, but . . . we should not depart from its essential content”.

Among the post-1969 tactics the Indian Affairs bureaucracy adopted to control and manage Indians, in order to continue the federal off-loading and assimilation goals, was to increase program funding for housing, education, infrastructure, social and economic development, health, and so on to band councils. This funding was delivered through federal funding agreements with strict terms and conditions for band councils and band staff to deliver essential programs and services primarily to on-reserve band members, goals and results designated by Ottawa. In other words, social engineering.

This transfer increased Indians’ dependency on the federal transfer payments and ensured accountability to Ottawa bureaucrats, not community members, through a system of indirect rule by band councils. They are expected to manage local discontent with chronic underfunding and underdevelopment on-reserve.

Another tactic for control and management of Indians used by Ottawa bureaucrats and politicians was to change the terms and conditions for funding of Aboriginal Representative Organizations (AROs) into two-part funding: 1) basic core and 2) project funding. Project funding means that to really survive, AROs need to develop funding proposals to the federal government to act as consultative bodies for federal government policy/legislative initiatives.

This is how the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), a National Aboriginal Organization (NAO), is funded, and how all of the Provincial/ Territorial Organizations (PTOs) are funded, which is why you rarely see the AFN National Chief, Regional Chiefs or PTO Leaders out at, or initiating, protests. From the band office, to regional First Nations organizations, to the AFN, Ottawa controls and manages the chiefs, leaders, and AFN National Chief and Executive through control of organizational funding.

The AFN uses Department of Indigenous and Northern Affairs (INAC) lists of chiefs recognized under the Indian Act as the official delegate list at AFN Chiefs’ Assemblies. So, the circle is complete. The Indian Act empowers INAC to rule over Indigenous peoples. The Assembly of First Nations has to align its own policies and structure with the INAC objectives and operations in order to get the funding it needs to exist. INAC then funds the AFN to carry out its program objectives and to administer the services it wants administered. And the grassroots Indigenous people are left powerless and voiceless within this closed system of governance.

Russell Diabo is one of the leading voices in the decolonial struggle in Canada. He was for many years a policy advisor at the Assembly of First Nations and now serves in that role for the Algonquin Nation Secretariat, and he is Senior Policy Advisor to the Algonquin Wolf Lake First Nation. He is also editor and publisher of an online newsletter on First Nations political and legal issues, the First Nations Strategic Bulletin. He is a member of the Mohawk Nation at Kahnawake, and part of the Defenders of the Land Network.