Section 2 : Southern Door ~ Learning with Open Heart and Mind

Chapter 3: Cultural Practices ~ Indigenous Ways of Knowing, Being and Doing ~ Terms, Identity and Meaning

Introduction

I have been teaching Indigenous courses at the post-secondary level since 2004. Prior to that, I taught at Saint Thomas University, New Brunswick for five years (1995-2000), and started at UPEI in 2002. While at Saint Thomas University with the Department of Sociology, I taught Introduction to Sociology and Social Problems I & II. As a class project in 1997 for Social Problems, we invited the National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations, Ovide Mercredi, who accepted our invitation to give a guest lecture. It quickly turned into a very special academic address open to the public with well over 300 people attending including many First Nation peoples from one of the five communities and my class of about 20 students. Chief Ovide Mercredi began by saying, “I have been invited here to talk about social problems. I think the official title of the course is Social Problems I, which I know something about given my role; but, let’s talk about Social Problems II if you don’t mind”.

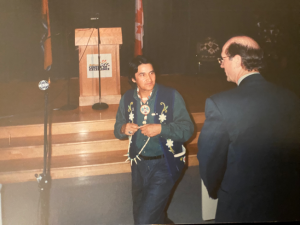

The National Chief spoke for 3 hours without pause, and provided everyone with a most in-depth and profound education respecting Indigenous peoples and the ‘Crown’. There was no topic not covered. Chief Mercredi spoke about cultural practices, ways of knowing, being and doing, and the importance of land as the way forward for Indigenous peoples and Canada as a country. He stressed this latter issue was behind the social problems that plagued the First peoples of this land since signing the ‘Treaties’. This was my introduction to Indigenous education and a national Indigenous leader of such intelligence, presence, and reconciliatory vision (see Figure 17).

Figure 17: National Chief Ovide Mercredi, Special Academic Address, Chatham, NB (1997)

There have been four National Presidents, first with the National Indian Brotherhood (1968–1970: Walter Dieter; 1970–1976: George Manuel; 1976–1980: Noel Starblanket; and 1980–1982: Delbert Riley), and then 12 National Chiefs with the Assembly of First Nations (1982–1985: David Ahenakew; 1985–1991: Georges Erasmus; 1991–1997: Ovide Mercredi; 1997–2000: Phil Fontaine; 2000–2003: Matthew Coon Come; 2003–2009: Phil Fontaine: 2009–2014: Shawn Atleo: 2014: Ghislain Picard (interim); 2014–2021: Perry Bellegarde; 2021–2023: RoseAnne Archibald; 2023: Joanna Bernard (interim); and 2023–present: Cindy Woodhouse). Without going into exhaustive detail regarding their respective agendas, it is safe to say that greater access to land and land claims have been high on each of their priorities as they advocate for the 630 First Nations in Canada (The Canadian Encyclopedia, 2023). As Wab Kinew, now Premier of the Province of Manitoba, wrote in the Huffington Post, “the Assembly, and its forerunner the National Indian Brotherhood, has been instrumental in seeking justice for Residential School Survivors and fighting for Aboriginal and Treaty Rights. That is not a legacy to be discarded” (Kinew, 2014).

I taught many Indigenous courses. In 2004, I began teaching a special topics course entitled, SAN 359: Contemporary Aboriginal Issues and Perspectives during the summer session until 2013. Students recommended that the course be available during the regular academic calendar year so it could reach as many students as possible. In January 2015, following full Departmental and Faculty of Arts support, I began teaching SAN 2220-1: Aboriginal Peoples in Canada, and I continue to teach this foundational area course for the Department of Sociology and Anthropology, primarily in the Fall semester. Since the release of the TRC Final Report and Calls to Action in 2015, I have introduced many Indigenous courses including IKE 1040: Indigenous Teachings after our Faculty was created. My introductory and upper-level Indigenous courses contribute to the on-going work of reconciliation, decolonization and Indigenizing the Academy (University) and in full support of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s Calls to Action.

I provide this context as a way to introduce my academic work. However, it is my public service work with Correctional Services Canada that helped me better understand Indigenous ways of knowing, being and doing. It was this work that brought me in direct contact with many prominent Indigenous Elders and Knowledge Keepers, who taught me about the ways of Indigenous peoples and, in particular, healing work. These Elders and Knowledge Keepers were from many diverse Indigenous communities across Canada. Some were distinguished Indigenous scholars themselves who successfully navigated two worlds – the Western dominant society world and the Indigenous world. I like to honour these Elders, and do so via a presentation I titled, Elders I Have Known, which was also a photography installation I exhibited at ‘the wall’, University of Prince Edward Island in 2015 (see Figure 19).

Figure 18: Elders I Have Known Exhibit at ‘the wall’, University of PEI (2015)

I have mentioned throughout the opening chapters that it is our Elders, Knowledge Keepers, and Indigenous scholars who pass on key knowledges. Since 2004, when I began teaching Indigenous content, I have relied on one Indigenous author more than any other, that being, Dr. James S. Frideres, Professor Emeritus of Sociology, University of Calgary. Dr. Frideres “grew up on the Fort Peck Reservation in Montana. He received his BSc degree from Montana State University. He then attended Washington State University where he obtained his MA and PhD in Sociology and Social Psychology, going on to teach at the University of Manitoba from 1969-1971 before moving to the University of Calgary. At Calgary, he has held a number of senior administrative positions. He has also been a visiting professor at a number of universities such as McQuarrie University, Dalhousie University, University of Hawaii (Manoa) and Hanoi University” (Working Better Together: A Conference on Indigenous Research Ethics, 2015).

I first started using his 2001 co-authored, Frideres, James S. and René Gadacz, text, Aboriginal Peoples in Canada. If you would like to know more about his work, I would suggest listening to an interview he gave in 2013 which profiles the Oxford University Press release, titled First Nations in the Twenty-First Century. Eventually, this text was transformed into Indigenous Peoples in the Twenty-First Century, which I continue to use primarily in my 2000 level course (Indigenous peoples in Canada). I reviewed the manuscript for both his 3rd (2020) and 4th edition (2024) textbook.

I introduce you to the work of Dr. Frideres as I include two readings for this book. The first reading is his chapter titled, Indigenous Ways of Knowing. The next reading will be found in next chapter that looks at the history of Canada in relation to Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. His written work continues to be a source of significant knowledge for many audiences including our students. I now turn to the main topics of this chapter.

Topics at a Glance

- Cultural Practices and Worldviews

- Indigenous Ways of Knowing

- Blending Western and Indigenous Knowledges

- Terms, Identity and Meaning

Let us now to delve into Indigenous peoples’ cultural practices and worldviews.

Cultural Practices and Worldviews

I want to begin by saying, Indigenous peoples are not a homogenous people. You will have noted already that ‘people’ is always written for the better part in the plural in recognition of the diverse nature of Indigenous peoples in Canada and across Turtle Island. This therefore means that for every distinct people or cultural group that is a corresponding unique culture and related practices. In this regard, Indigenous peoples are a heterogenous population.

I think that a quick tour of the Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada (Canadian Geographic, 2018) will immediately reveal the distinct nature of the three main cultural groups of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit that comprise Indigenous peoples in Canada. This source (physical copy located at Robertson Library) will give you an excellent overview of all aspects of these cultures and practices including such aspects as connection to the land, arts and culture, traditional ways, ceremonial spaces, language, etc. Former National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), Harry Bellegarde, who provided the Introduction to the Atlas, writes,

“Culture is not static, and our challenge is to navigate our worlds in ways that respect and honour traditions but also make room for growth and evolution. The balance of blending modern and traditional worldviews is reflected in a variety of captivating stories that include Dene music and drumming and the traditional Haudenosaunee game of lacrosse. We also provide a glimpse into the challenges of maintaining our connections to the land and culture as part of the urban experience in Treaty 1 territory” (Canadian Geographic, 2018)

I will then say that there is no way in one chapter, one session, or one course that anyone will master or even remember all of the information as it relates to cultural practices or worldviews. However, since we have to start somewhere, I begin with several ‘warm-up’ videos. They are:

Indigenous Culture | Spectacular NWT, Canada

Canada History Week 2021 – Indigenous Culture

Learning Indigenous Culture in Canada

I welcome you to explore the following videos that profile Indigenous peoples in the United States. The first video is short; but, the second is much longer. Yet, it is exceptionally well done.

A Brief But Spectacular take on Indigenous cultures and struggles (United States)

Against the Current | A Short Documentary About the Culture of Indigenous People (United States)

You will learn much more about Indigenous peoples and their respective cultures throughout this course. This is only the beginning. Let us now examine another aspect of Indigenous peoples and their ways of knowing.

Indigenous Ways of Knowing

You will have read James Frideres’ chapter on Indigenous ways of knowing. Although there is a significant amount of information respecting the Western ways of knowing, primarily founded in the scientific method, and that scientific truths and theories are outside the knower. There is a commitment, rightly or wrongly, to empirical evidence, a necessity for reductionism, adherence to the laws of cause and effect, the subservience of nature where nature is assumed to be capable of manipulation by humans, and a commitment to a realistic or “objective” quantifying view (Frideres, 2020, pp. 44-59).

What is it about? What are the main takeaways? Did any of this come as a surprise? How do relate to the worldviews as summarized from the reading:

- Comprised of a complex set of technologies sustained by Indigenous people

- Embedded in the accumulative experiences and teachings of the people

- Based on people’s skills and adaptable to problem solving and change over time

- Features unique internal consistency and postulates

- Knowledge pertains to particular people and a territory

- Indigenous ontology is distinct with equally distinct epistemological validation of the knowledge found in the culture

- Indigenous knowledge is subjective experience and forms the basis of an objective explanation of the world

- All animate and inanimate beings have a life force and a spirit, which are an essential part of balance

- Indigenous ways of knowing are based on the local environment

- Language, space, and the relationship evolve over time to reflect interactions with the environment

- Land is recognized as the source of life

- Severing cultural connections also destroys the meaning of the behaviour and the understanding of the context

- The ceremonial context is essential to accessing or knowing Indigenous ways of being

- Everything is animate and has a spirit in the Indigenous worldviews

- All things are in relationship

- An ontological belief is that people travel through life in a relational existence focusing on knowledge, animate and inanimate objects, participating fully and responsibly in relationships which are more important than reality

- When a person comes into a relationship with certain knowledge, he or she must assume responsibility for it

- Ceremony is the one way in which the relationship is carried out with respect

- To live properly one must stay in harmony and balance with nature for the sake of the community’s survival

- Inner space is the reality of being in harmony with the self and the environment; knowing one’s place in the universe

- All the elements of the universe in balance; gives meaning to existence

- Indigenous ways of knowing are grounded in the idea that a continuum of change and events take place in cyclical fashion

- This idea has become the foundation of the philosophy, strategy for surviving and Indigenous ways of knowing

- We are connected to the world around us with the animals, plants, mother earth, and the cosmos

- The key to Indigenous knowledge is to understand change as a whole

- Indigenous culture is rooted in the place and the nature of place embedded in their language

- Language allows the physical, cognitive, and emotional orientation of a people

- Language provides an intergenerational map of the world

On Elders, Frideres reminds us that

- An Elder is someone who has a deep understanding of Indigenous ways of knowing and who understand the spirituality that embodies all their actions

- Elders understand the importance of respecting the natural world

- Elders share the teachings through ceremonies, e.g.: sweat lodges, healing circles

- Teach others about the culture and traditional ways, vision of life, and validated knowledge within their local environment

Frideres sums up the chapter this way:

- Indigenous people must create a different equilibrium that balances their beliefs in creation and ceremony

- Their axioms and postulates are different from the Western worldviews

- Indigenous knowledge is based on relational reality

- The Indigenous way of knowing is thousands of years old

- Indigenous ways of knowing increases awareness and a better understanding of the culture

- It is being accountable to your relations

After reading Frideres were you somewhat conflicted? Were you trying to gauge which paradigm or worldview (Western or Indigenous) is correct or had more explanatory power than the other? What about other world peoples and their respective worldviews? Does one worldview have to be dominant and/or adopted as the only way of knowing, being and doing? Maybe we need to explore this further in the next section.

Blending Western and Indigenous Knowledges

There is a concept that I was introduced to when I was doing my Correctional Services Canada work as it related to creating a substance abuse treatment program for federally-incarcerated Indigenous men. I would like to discuss the concept of “Using Medicines on both Sides of the River“, coined by my mentor, Dr. Joseph Couture (see Figure 19).

Figure 19: Dr. Joseph Couture, Willow Cree Healing Lodge, SK (2003)

Dr. Joseph Couture, Maskwacis (Hobbema) First Nation, Alberta was the First Indigenous Ph.D. in Psychology in Canada. Dr. Joe as he was known was a well known author, healer, academic (former Chairperson at Trent University’s Department of Indigenous Studies), and the National Aboriginal Achievement Award Recipient in Health in 2007. He passed to the spirit world shortly after having received this national award and after I dedicated the Aboriginal Offender Substance Abuse Program (AOSAP) to him and all the Elders who helped me bring this important national work of healing to fruition. I was honoured to know him, and he was one of the many Elders I Have Known. Sometimes I take a minute to listen to him in my heart and mind, and occasionally his words, which were recorded by Indspire for the Award ceremony.

We will look at his legacy later in this textbook as I had the opportunity to put ‘Using Medicines on Both Sides of the River’ into practice.

In Mi’kmak’i, we have another concept that has been frequently used, and has gained national and international recognition. The term, “Etuaptmumk – Two-Eyed Seeing“ was coined by Dr. and Elder Albert Marshall. It is a term similar to that expressed by Dr. Joe. I provide several links below where you can learn more about “Two-Eyed Seeing”. The first is an interview with Dr. Albert Marshall. The others allow you to explore other aspects of the concept. Dr. Marshall’s work at the Unama’ki Institute of Natural Resources, Cape Breton University, has been highly acknowledged as advancing Indigenous ways of knowing in the scientific domains of Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM), and especially attracting Indigenous students’ enrolment in these fields.

Albert Marshall Interview with Chris Beckett (2018)

Albert Marshall | Unama’ki Institute of Natural Resources

Etuaptmumk: Two-Eyed Seeing | Rebecca Thomas | TEDxNSCCWaterfront

I trust you have a good sense of the importance of blending, integrating, and using multiple perspectives. To coin the Truth and Reconciliation of Canada, it’s about ‘working together’. We shouldn’t have to be reminded of this; but, we occasionally do. The last section in this chapter examines terms, identity and meaning.

Terms, Identity and Meaning

Like most of the content in this course, there is so much information to review and consider. You will have already read, Chapter 1: Just Don’t Call Us Late for Supper (pp. 7-13) from Chelsea Vowel’s 2016 Indigenous Writes: A Guide to First Nations, Metis and Inuit Issues in Canada. If you wish to hear more about Chelsea Vowel, and how she developed her text, you can listen to an audio recording of her at Indigenous Writes : One Indigenous Person’s Journey. There are many takeaways from her easy to follow offering. What were they? Navigating terms, examining issues of identity, and understanding the meaning(s) behind words, concepts and the language and thinking of Indigenous peoples are monumental. Again, it’s not an easy task; but, there are many resources from which to make sense of all of this.

You may recall, I provided a link to access the following document: UBC’s Indigenous Peoples’ Language and Terminology Guidelines (2021). This 19 page document is exceptionally well-done, very thorough, and should give you some very important information respecting terms and terminology. There are other links I provide below which can be accessed as well.

What does it mean to be Indigenous? | National Indigenous Peoples Day (2022)

What does being Indigenous mean?

I will introduce my own story of being Indigenous during the lecture portion of the course. It’s from that which i hope you will start to make connections about terms, identity and meaning. Below you will find the key terms and concepts from the chapter.

Key Terms and Concepts from Chapter

- Assembly of First Nations (630 First Nations)

- Reconciliation, decolonization and Indigenizing the Academy (University)

- Cultural Practices

- Worldviews

- Elders, Knowledge Keepers, Indigenous Scholars

- Ways of Knowing

- Western Science: Scientific Method-Objective-Reductionism-Empirical-Causal-Linear

- Indigenous Knowing: Complex-Relational-Cumulative Experience-Adaptable-Sustainable-Territory-based

- Holism~ Space/Land~ Relations/Reciprocity~ Fluidity/Natural ~ Environment Rhythms ~ Language

- Integration of contemporary best practices with culturally appropriate approaches (i.e., a blended approach)

- Evidence-based research

- Using Medicines on Both Sides of the River

- “Etuaptmumk – Two-Eyed Seeing”

- Terms respecting Indigenous peoples vs. inappropriate (Vowel)

- Identity

- Individual journeys and teachings

Important Readings / Viewings for Next Class

- Chapter 1: Knowing Your History (pp. 1-24) in Frideres, J. S. (2020). Indigenous peoples in the twenty-first century. Oxford University Press.

- Chapter 2: Mi’kmaq Social Values and Economy (pp. 23-43) in Paul, D. N. (2000). We were not the savages: A Mi’kmaq perspective on the collision between European and Native American civilizations. Halifax, NS: Fernwood.

Special Topics

Indigenous Ways of Knowing & Doing Across the Academy

Cultural Competency Tutorials

Interviewing Elders – National Aboriginal Health Organization, UVic, 2013